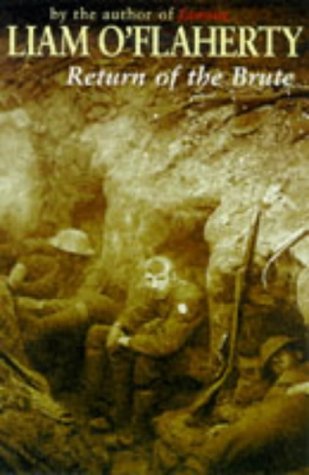

As the official celebrations and the unofficial commemorations of the centenary of the First World War continue, many personal accounts, poems and novels written about this period have been published or republished. One novel, not yet republished, is Return of the Brute, written by Liam O’Flaherty. David Trotter, in The Cambridge Companion to The Literature of the First World War, argues that, unlike most British war novels, it was written by an author of proletarian origin. Whilst O’Flaherty was Irish, Trotter is right in considering Return of the Brute to be a British war novel. It is based upon the author’s experiences fighting in the British army on the western front. The novel “intended to do justice to the brute’s point of view” [1], where the “brute” stands for working-class soldiers. If so, the “brute” refers to atomised, alienated and demoralised workers, brutalised by life on the western front.

However, the “Return of”, in the novel’s title, suggests the recent existence of a very different, collective and class conscious working class, which had learned to challenge the brute status of workers as individual wage slaves under untrammelled capitalism. The First World War had been preceded by the heady days of the 1913 Lock Out in Dublin, with the Irish Transport and General Workers Union and the Irish Citizen Army (ICA); by the women’s Irish Textile Workers Union formed in 1911 in Belfast; and by the activities of Irish-American copper miners in the Industrial Workers of the World, in Butte, Montana, the most unionised city in the USA.

The retrograde impact of the First World War on the consciousness and behaviour of workers can be seen as the subject of Return of the Brute. The novel covers a few days of No. 2 Platoon’s experiences on an unidentified section of the Western Front in May 1917. The platoon is made up of No. 7946 Corporal John Williams, grocer’s assistant; No. 8740 Private George Appleby, labourer; no.9087, Private Michael Friel, policeman; No. 11145 Private Simon Jennings, the somewhat reprobate son of a bishop; No. 8637 Private Jeremiah Macdonald, farm labourer; No. 4048 Private Daniel Reilly, bookmakers’ tout; No. 8356 Private William Gunn, general labourer; No 12468 Private Louis Lamont, 19 year old student; and No. 3920 Private James Shaw, excise officer [2].

However, the soldiers’ former occupations and social status have become irrelevant. So too have their places of origin. The latter are not given, with the exception of Friel, who is described as having been in the Royal Irish Constabulary, and Gunn, an Irishman who had lived and worked in the USA and Canada, before returning to join the British Army. The soldiers’ surnames do suggest these men may have come from English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh backgrounds. However, the experience of war, and the long period of suffering they have undergone on the front – shelling, mud, rain, lice and hunger – have eliminated all such differences. Even when it comes to the fighting, O’ Flaherty writes that, “Sergeant-Majors, trenches, positions and the enemy, with his rival organisation of officers, orders, trenches and positions, all disappeared and became meaningless’ [3].

Private Gunn is the central figure in Return of the Brute. He is already a flawed individual, “married once to a woman, way up in Nova Scotia… I left her one night after giving her a bloody good hiding” [4]. Gunn compares her to the young Lamont who lives in constant fear. “She was just like you” [5]. The only women who seem to be viewed positively are soldiers’ mothers.

When Gunn sees individual failings around him, he often falls back on blaming women. The brutalising effects of war on men can be seen clearly through O’Flaherty’s descriptions of the unrelenting horror of life at the front. In comparison, Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s Sunset Song describes the psychologically destructive impact of shellshock on Ewan Tavendale, when he returns to Kinraddie on leave, a changed man. He goes on to casually and thoughtlessly abuse his wife, Chris Guthrie, the central character in Gibbon’s book.

Yet there is a human side to Gunn. He takes the young Lamont under his wing to protect him from “Authority”. Lamont is trying to work out how he can escape all the horror of the trenches. Gunn tells him, “There are only two ways. You either go West or get a blighty” [6] – you get killed or receive a serious enough injury to be removed from the front. Some soldiers try to injure themselves. But, “What happens?… Them blokes back there {Authority} are too cute… They’ll cop you. Sure as hell…. If you try on any silly stunt, they put you in dock until you get better and then you’re for it” [7].

When a particularly stupid order (and the novel contains several such) has the platoon wandering aimlessly about in No Man’s Land, and “a groan of anger passed along the line…. It was a groan of revolt against Authority, but it had no power behind it” [8]. Instead, the men fall back on the camaraderie of being a soldier with immediate ties only to others in their platoon. When some of them die, they too are soon forgotten, or their memory treated disrespectfully, due to the demoralising effect of the lack of rations and sleep on the other soldiers.

Gunn tries to persuade others in his platoon what the true situation is. He tells Shaw, “You’re only a slave. You think because you’re an old soldier you’re something. But you’re only a slave. A bloody machine” [9]. Later, with several of the platoon already dead, he tells Reilly, “A good soldier means one thing to you and me, but it means another thing to THEM. To you and me it means a MAN. To them it means a —- clod” [10].

Gunn knows of the people who are responsible for their fate. “I don’t give a curse who wins this rotten war and I’d run my bayonet through the fellahs that started it” [11]. However, isolated as an individual, he cannot get at “Authority”. He is humiliated by Corporal Williams (and another officer) after an act of insubordination. “The two NCOs…. wanted to use Gunn as a butt for maintaining the iron discipline which is necessary to make soldiers suffer the unspeakable tortures and indignities of war with resignation” [12]. It was not the two NCOs “who annihilated him, but the authority they represented, the great machine, covering the whole battle front, like a sprawling colossus” [13].

Unlike the others in the platoon, Gunn can see what they are up against. The men begin to die – drowning in the mud, or of horrible wounds. Feeling helpless, Gunn decides the only role left for him is to save Lamont. But he fails and Lamont dies of the cold in the trenches, having given up the will to live, after yet another ill-planned operation dreamt up far from the front lines.

Gunn’s mind, “Expanded, contained a picture of the whole army, from Commander-in-Chief with his staff, right down the ranks of Authority, to the great nameless, numbered multitude of men like himself, who lay hungry and wet and covered with mud in holes, DOOMED TO DIE…” But, “Contracted he saw in it only the Corporal and himself” [14]. And it was only in this contracted and immediate world of the front that Gunn can hope to influence anything, so the Corporal looms large in his thoughts.

In a raid on the German trenches, Gunn turns on Corporal Williams and, after a struggle, chokes him to death. He has already tossed a bomb into the adjacent crater in an attempt to kill Williams, but kills Macdonald instead. Having been driven insane, Gunn wanders aimlessly and is mown down by German machine gun fire. These events accentuate the futility of his individual act of defiance.

The novel finishes:- “No. 4048 Private Daniel Reilly was the only one of Corporal Williams’ section who came back alive” [15]. Perhaps the fictional Reilly is needed as the story’s witness for these events. If so, then he is acting as a surrogate for O’Flaherty, who uses his own knowledge of life in the trenches for his novel.

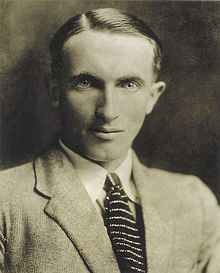

What makes this novel particularly interesting is O’ Flaherty’s background [16]. He was born in 1898 to a bilingual Gaelic and English family on Inis Mor, the largest of the Aran Islands. In 1917 he joined the Irish Guards and was badly injured at the Battle of Langermarck. Later in life, he was to suffer mental disorder, probably as a result of the shell-shock.

It is significant that O’Flaherty’s sojourn in the British Army occurred after the 1916 Rising. A fundamental divide is often drawn between those Irish people (because the ICA included women as well as men) in the Republican forces who took part in the Rising, and those Irish men who fought for the British.

Those fighting for the British included the 36th (Ulster) Division mainly made up from the Ulster Volunteer Force. In 1912 Sir Edward Carson had helped to set up the UVF, in opposition to the 3rd Irish Home Rule Bill. However, many in the Irish Volunteers, formed in 1913 to defend Irish Home Rule, were also encouraged by John Redmond and Joe Devlin of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) to join the British Army. They also had to prove the loyalty of the Home Rule supporting Irish-British.

The participation of so many Irish soldiers enabled the British War Coalition, with the backing of several IPP and British Labour leaders, to describe the 1916 Easter Rising as an act of treachery. Others have dismissed it as nothing but a “blood sacrifice”. There were 485 deaths, including 260 civilians, the majority of whom were killed by the British Army.

However, many more Irish soldiers serving in the British Army had already been killed, particularly at Gallipoli. This was highlighted in the well-known song, The Foggy Dew, written by Canon Charles O’Neill after the sitting of the First Irish Dail in 1919.

‘Twas better to die ‘neath an Irish sky

Than at Suvla or Sud-el-bar[17]

But the writing of that song still lay in the future. Almost as soon as the 1916 Rising had been crushed and its leaders executed, between May 3rd and May 12th, another much bloodier battle was to take place – the Battle of the Somme.

Just as O’Flaherty portrays the sense of doom on the front in Return of the Brute, Frank McGuinness gets across a feeling of foreboding in his play, Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme, written in 1985. The battle lasted from 1st July to 18th November 1916. It cost over a million casualties, including the lives of 310,186 Allied and German soldiers. In two days of fighting alone, the 36th (Ulster) Division lost 5500 men, killed, wounded or missing. It truly was a ‘blood sacrifice’. Some of those missing were probably accounted for by drowning in the mud. This horrific death is harrowingly described by O’Flaherty when, aching with hunger, Private Appleby tries to stretch out for two cans of corned beef and falls into the mud [18].

The ‘Battle of the Somme’ joined ‘1690’ in the Ulster Unionist pantheon. Carson had already joined the War Coalition in 1915 to ensure that it was the Unionists’ voice, and not that of Irish Home Rulers, who would be heard by the UK government at the end of the war. When the 1916 Rising occurred, the time for another British General Election had passed. One of the motivating forces behind the 1916 Rising was the further Right slippage of the British War Time coalition, with the support of the Conservatives and Unionists, who opposed Irish Home Rule.

Ironically, it was the 1916 Rising, which probably persuaded an otherwise victorious, gung-ho, post-war British government that it would have to concede some form of Irish Home Rule after all. Carson’s ‘blood sacrifice’ though meant that ‘Six Counties’ were kept out of the post-war Irish Home Rule arrangements. But Home Rule proved to be ‘too little, too late’. After the 1919-21 Irish War of Independence, the ‘Six Counties’ were also excluded from the new Irish Free State.

The fatally divided Irish working class, whether Protestant or Catholic, Unionist or Nationalist, found that any ‘blood sacrifice’ they had made during the war, gave them little protection. Instead, they faced demands, from both the Ulster Unionists in Belfast’s Stormont and Cumann na nGhaedheal in Dublin’s Dail for more sacrifices (with the City of London pushing austerity behind the scenes). The working class and small farmers bore the brunt of the prolonged postwar economic recession and then the Depression. In 1913, James Connolly had predicted such a “carnival of reaction” if Partition were to be imposed.

Yet, the depth of the 1916 divide, argued for by contemporary British unionists and Irish Home Rulers, and still maintained by revisionist historians today, ignores some vital facts. In the 1918 UK General Election, Sinn Fein easily won the Dublin constituency that included the GPO, despite the claim by British propagandists that there was little support for the 1916 rebels in Dublin.

Some have claimed that the massive electoral shift towards the Republicans only came about due to the British government’s callous shooting of the Rising’s leaders, and their attempted moves to introduce conscription in 1917. However, ‘the Brits ballsed it up’ arguments downplay the impact of the horrors of the war itself on those soldiers, including the Irish-British. Return of the Brute vividly describes these. Furthermore, such arguments ignore the increased problems faced by the Home Rulers. They remained junior partners to an unsympathetic British government with other priorities. In contrast, Republicans, whether free or in prison, were able to take the initiative and gained support as a result.

Thus, even amongst those returning Irish soldiers, who had fought for the British in the First World War, many gave their gave votes to Sinn Fein in the 1918. And in 1920, the Connaught Rangers were to mutiny in India, demanding that all British troops be removed from Ireland.

Furthermore, some ex-British soldiers went on to use their military skills to fight for the newly elected Irish Republican government, when it was refused recognition by the British government. Tom Barry, had been a corporal in the British Army, and he fought at the Battle of Kut in Mesopotamia, and later in Palestine. Upon his return to Ireland, he joined the IRA, and became a legendary leader of the West Cork Flying Column, continuing to fight for the Republican Anti-Treaty forces from 1922.

And what did Liam O’Flaherty do after he returned from the war? He became a founder member of the Communist Party of Ireland. The CPI supported the Irish War of Independence, seeing it, in effect, as part of the International Revolutionary Wave, which had started prematurely in Dublin 1916. It had been given much greater impetus by the Russian Revolution in 1917. Indeed, the threat of spreading revolution contributed to the ending of the war. This is what James Connolly had hoped would happen at the outbreak of the war.

But Flaherty also went on to give his support to the Anti-Treaty side. Two days after the declaration of the Irish Free State, on December 6th, 1921, O’Flaherty was joined by other unemployed workers and seized the Rotunda Concert Hall (now the Gate Theatre), on Parnell Square. They held it for four days, flying the red flag, before the Free State troops forced their surrender.

A penniless Flaherty moved to England, where he became a writer. His first successful novel, The Informer, was written in 1925. His cousin, John Ford, born Jack Feeney (whose mother came from Inis Mor before the family moved to the USA), made a Holywood film from this novel.

Return of the Brute was written in 1929. What it highlights is the need to appreciate the impact of the events of the First World War, and the International Revolutionary Wave that came out of this. Together, they brought big changes in people’s allegiances. The majority in Ireland stopped considering themselves to be Irish-British and became Irish [19]. The novel helps to make this transition more understandable.

By the time O’Flaherty wrote this novel, the transition from Irish-Britain to Irish Ireland in twenty six counties, and to the Northern Ireland of the ‘Ulster’[20]-British in six counties, had taken place. O’Flaherty had continued to play his part, no longer as a British soldier, but as a Communist and Irish republican writer. The importance of class in this struggle is emphasised negatively by his experience of the “brute”, and positively by his switch to collective, class conscious, socialist republican politics.

Return of the Brute should be republished, maybe to coincide with the 2017 centenary of its story.

Allan Armstrong, 9.12.16

References

[1] David Trotter, British War Memoirs in The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of the First World War, edited by Vincent Sherry, p. 35, Cambridge University Press, 2005,

[2] The page numbering comes from the paperback edition of Return of the Brute (RotB), by Liam O’Flaherty, published by Wolfhound in 1998. This is from pp. 37-41.

[3] RotB, p. 49

[4] RotB, p. 15-6

[5] RotB, p. 15

[6] RotB, p. 13

[7] RotB, p. 18

[8] RotB, p. 52

[9] RotB, p.101

[10] RotB, p.119

[11] RotB, p. 15

[12] RotB, pp. 56-7

[13] RotB, p. 56

[14] RotB, p. 81

[15] RotB, p. 139

[16] The information about Liam O’Flaherty’s life is taken from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liam_O%27Flaherty

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foggy_Dew_(Irish_ballad)

[18] RotB, pp, 62-4

[19] For more on this see Section B – From the Irish-British ‘Insider’ and the Irish ‘Racialised’ and ‘Ethno-Religious Outsider ‘to the new ‘National Outsider’ by Allan Armstrong at:- http://republicancommunist.org/blog/2016/03/02/britishness-the-uk-state-unionism-scotland-and-the-national-outsider/

[20] The nine county province of Ulster which the Ulster Unionist Party initially adopted as its geographical organisational framework, was itself partitioned, with six counties becoming Northern Ireland and three counties going to the Irish Free State. The UUP had to adjust its organisation accordingly, much to the chagrin of its abandoned members who had lived in the three counties.

__________

This has also been posted by the Liam and Tom O’Flaherty Society at:-

https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=732256583588411&id=154178324729576

_____________

Other reviews and review articles by Allan Armstrong

The Story of Sandy Bells, book written by Gillian Ferguson

‘THE STORY OF SANDY BELLS: EDINBURGH’S WORLD FAMOUS BAR’ – A review

Even the Rain, film written by Paul Laverty, directed by Iclar Bollain

The Road of Tears, CD by Battlefield Band and La Radiolina, CD by Manu Chao

The Provisional IRA- From Insurrection to Parliament, books by Tommy McKearney, edited by Paul Stewart

From Grant Keir

Check this out! Interesting to see that a film version was made in Britain in 1929 before it was made by John Ford in the USA. Also see how well Ford’s film did in the Oscars!!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Informer_(1935_film)

See also:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TX5YSIxphz0

See also: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0020025/

Interesting footnote is that the 1929 version was made as films became ‘talkies’ and it starts as a silent film but has dialogues from about 45 mins in… The lead actors were Swedish and Hungarian, so it is all a bit weird, but the expressionist camera work clearly influenced John Ford’s later much more successful remake.

Return of the Brute would be such a refreshing antidote to the revisionist history that the 1914-18 war period has been systematically subjected to these past years…

Cheers!

Grant

From Jim Aitken

I enjoyed reading that, Allan. While I have read a few of O’Flaherty’s books including The Informer and visited his home on Inishmore, I did not know the Return of the Brute.

I knew about O’Flaherty’s communism and the Rotunda occupation but your linking of The Return of the Brute and Sunset Song was excellent because both books spring from a working class revulsion of war, a war that disfigures human relationships between man and woman and man and man. I think it was MacLean who said it was a worker at each end of a bayonet.