Adrian Kerr, Free Derry – protest and resistance, Guildhall Press, 2013, pp. 224, £11.95

From the declaration of ‘Free Derry’ on August 9 1971, when the solidly working class and republican community seized control of their own area of the city of Londonderry, to the time of the Provisional Irish Republican Army ceasefire in 1994, the price paid and the degree of resistance mounted within it was hugely inordinate, by comparison with occupied Ulster as a whole.

One hundred and twenty-two people lost their lives in and around the Free Derry area, including 73 civilians and republican volunteers, and 49 members of the security forces or civilians working for them. Over 3% of the total deaths for the whole of the conflict occurred in an area containing less than 1% of the population of the north of Ireland. The largest number of killings were committed by the ‘security forces’ – 46 died at the hands of either the British army or the Royal Ulster Constabulary, 33 of whom were civilian non-combatants.

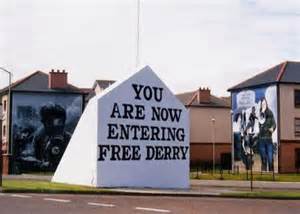

This is a remarkable book. Not least because it is the only book to have been written about the Free Derry ‘commune’, as we could correctly call it. That creation was shapeless, spontaneous, episodic and heroic. The people of this risen community decided enough was enough and they would no longer be prey to loyalist murder gangs, sectarian armed police, and later the full weight of the British army. They claimed it back, shutting it off from the authority of the British state, taking the whole area under their own direct control and administration.

This rattled the British ruling class no end. The initial ‘Hold back and it will peter out’ response of the authorities was to cause furious contempt among sections of the British forces. Not least major-general Robert Ford, commander of land forces for regiments stationed in Derry in 1971-72. The tactical decision not to go in and re-impose British control over this republican stronghold for the sake of appearance was taken almost personally by Ford as a sign of weakness and tantamount to surrender. It was Ford who was to bypass the forces on the ground, employing a detachment of Paras brought in from outside with the clear intention of showing the people of Derry who was boss. At the end of the bloodbath that was Bloody Sunday (January 30 1972) 14 utterly innocent people lay dead, many with multiple bullet wounds, some summarily executed as they lay bleeding and helpless on the ground.

The book leads us through the narrative of mounting resistance: the non-violent civil rights campaign to win ‘one person, one vote’ – incredibly not all adult Catholics were enfranchised, while Protestant businessmen could quite legitimately exercise more than one vote through the property franchise. The weighing of the ballot to favour one political community regardless of population size was a throwback to the ‘rotten boroughs’ prior to the 1832 Reform Act, and complemented the gerrymandering of borders which already ensured a loyalist electoral majority, even when clearly outnumbered by republicans. The monolithic nature of Stormont, with its cast-iron loyalist control, ensured that the Catholic republican community would be confined to specific ghettos and housing would not be allocated on the basis of need, but on the basis of religion and politics. The injustice of the situation cried out for a remedy, but the simple demand for constitutional equality in line with the rest of ‘Britain’ brought down upon the petitioners the most vulgar and unrestrained violence and repression, and basically beat the pacifism and non-violence out of the movement.

As the narrative unfolds, each death is recorded in the book on a differently shaded page – and the shaded pages increase in number as the story moves on. I thought I had understood fully the process of events, but I know now I was missing shades of grey among what appeared to me simply black and white. Blow by blow and death by death, as the struggle matures and degree of resistance hardens, we follow here the history as few except those intimately involved would have understood and experienced it. The emergence of the Provisional IRA, with its new breed of young working class fighters, to meet the challenge and for a time face down 20,000 British troops, is something which in general ‘the left’ in Britain never, ever fully understood – perhaps with the benefit of distance and reflection, that movement might become clearer now. But the book tells the whole story here, warts and all.

As I read, my own understanding of the struggle was severely dented on a number of occasions, not least by the record of armed struggle engaged in by the Officials, who I had always believed were virtually confined to barracks throughout the bitter resistance. Not so by any means. This history goes to show that depending on the Provisional press and its version of history alone, as I had done, had not actually provided me with the whole picture.

Following the Bloody Sunday massacre, one might have thought – and the military strategists who planned the atrocity must have intended – that the spirit of the community would be broken. Not so – just the opposite. Almost every able-bodied man and boy in the community lined up to join both wings of the IRA, and the community imposed its control back on the streets again. In the months following, the IRA extracted a heavy cost on the army and RUC, while the British state fumed at the autonomy of Free Derry, establishing a think tank of strategists to draw up options on how to cope with the display of defiance and autonomy. Interestingly the relevant documents are now available – some of the options considered give you a clue as to how desperate the situation was believed to be. One of them involved cutting off Free Derry completely – a siege no less: no water, electricity, post or basic deliveries.

In the end they opted for Operation Motorman. The intention was to go with the panzers (Centurion battlefield tanks), armoured cars and 1,500 fully armed troops. As the tanks smash through road blocks and over rubble and barricades, there is something of similar world events in this scenario – Hungary comes to mind. They prepare for house-by-house resistance, they calculate high causalities, they expect innocent civilians across the board to die: they think it is all a price worth paying. But the IRA does not, and wisely refuses to fight this battle in its own backyard, within its own unarmed and vulnerable community. Free Derry, as an autonomous, self-operating and defended community was broken open on July 31 1972. It had lasted just a few days short of a year.

But the spirit (as well as the famous end-house mural) still remains. Now it is the clicking of cameras, not the discharging of rifles, that is heard, as folk from across the world come to visit the area, marvel at its history, study its legend and visit its wonderfully moving Museum of Free Derry, from which this book is derived.

Every person who calls themselves a socialist of any description must surely read Free Derry: protest and resistance andarm themselves with the knowledge of one of the most heroic pages of struggle of any working class community in the last century.

(this was first published in the Weekly Worker, see Free Derry review: Freedom for a year)

(also see Dave Douglass Reviews Gregor Gall’s ‘Tommy Sheridan, From Hero To Zero?’)