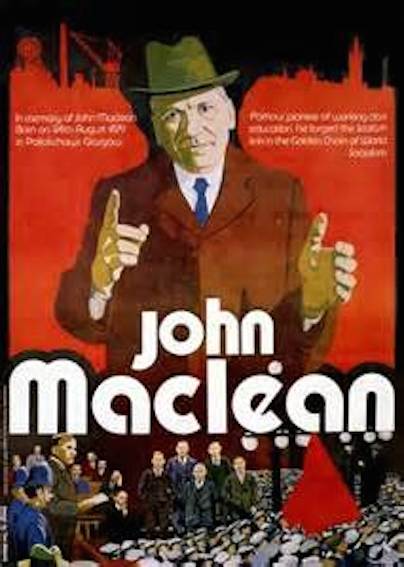

On November 30th, 1923, John Maclean, the great Scottish socialist, died, after two decades of committed struggle. Eric Chester (RCN) has written the following piece, which is a contribution to today’s celebration of John Maclean’s life.

JOHN MACLEAN – 1879 – 1923

Glasgow has a proud tradition of radical politics, one that is particularly important to remember when the government is promoting jingoistic celebrations of World War I centenaries. During the four years of that devastating conflict, the Glasgow working class engaged in a series of mass actions to protest the war and the profiteering that accompanied it.

One event that deserves special mention took place on May 1, 1918. By then, the war had been grinding on for nearly four years, with casualties already in the millions. Glasgow’s workers, who built the ships and many of the munitions deployed by the British military, were ready to act. Although many workers were eager to pressure the government to bring the war to an immediate end, the War Cabinet, a coalition of Tories, Liberals and the Labour Party, suppressed any open opposition.

Through his determined and courageous opposition to the war, John Maclean had become a folk hero among the Glasgow working class. Maclean had consistently urged the anti-war Left to move beyond merely passing anti-war resolutions to organising political strikes that would shut down the war industries. In early 1918, Maclean began pushing for a one-day general strike to commemorate May Day.

May Day had been marked by massive demonstrations in Glasgow for several years before World War I began in August 1914. Tens of thousands would march from different tenement neighborhoods to converge on the Glasgow Green. A dozen or more platforms were set up around the Green so that marchers could decide which speakers to listen to. Thus, no one organisation dominated, while everyone got the chance to present their point of view.

Still, as exciting as these marches were, they were planned for the first Sunday of May, which did not usually coincide with May Day. Work was therefore only minimally disrupted. Maclean sought to break this practice and proposed, instead, that the march be scheduled for May 1, with the explicit intention of making this a dramatic protest against the war.

For the first years of the war, Maclean and his small group of supporters within the Scottish division of the British Socialist Party had been isolated within the wider anti-war Left. Only in early 1918, as grass-roots support for a policy of active resistance rapidly grew, was there a widespread acceptance of Maclean’s strategy. A broad coalition of left-wing organisations called for a march to the Green to take place on May Day itself. Unfortunately, by the time the march took place, Maclean was again in prison for speaking out against the war.

On Wednesday, May 1, 1918, factories and shipyards throughout Glasgow and along the Clyde were closed as tens of thousands of workers quit work to join the neighborhood marches heading for the Green. The marchers held placards demanding a rapid end to the war and the immediate release of Maclean from prison, themes echoed by those who spoke to the crowd. It was a stirring day and one that should be remembered.

Nearly a hundred years later, May Day in Glasgow is celebrated by a lackluster march sponsored by the Scottish TUC. Once again, the march is held on a weekend and not on May Day itself. (By chance, the coming May Day falls on a Sunday.) The radical Left needs to revive the spirit of the true May Day, so that in the coming years we can renew the events of May 1, 1918.