Socialists are now confronted with the unexpected rise of Jeremy Corbyn and the re-emergence of British Left social democracy. This first part of this article by Allan Armstrong will examine the significance of this and make a critical appraisal of their future prospects in the face of the current global multi-faceted political, economic, social, cultural and environmental crisis.

Contents of Part 1

1. From May 2007 to June 2017 – the SNP rules the social democratic roost in Scotland.

2. The rise of Jeremy Corbyn and British Left social democracy

3. The prospects for Corbyn and British Left social democracy when handling economic and social issues

4. The limitations of Corbyn and British Left social democracy when dealing with matters of state

A. Brexit

B. The National Question

a. Conservative, liberal and unionist attempts to maintain the unity of the UK state since the nineteenth century

b. Corbyn and the National Question in Ireland

c. Corbyn and the National Question in Scotland

d. Corbyn and the National Question in Wales

1. From May 2007 to June 2017 – the SNP rules the social democratic roost in Scotland

i. Following the demise of New Labour and its successor, ‘One Nation’ Labour, the SNP has been the most effective upholder of social democracy in the UK. In 2007, the SNP won 363 council seats; 425 in 2012, and 431 in 2017. In 2007, the SNP won 47 MSPs; 69 in 2011; and 63 in 2016, (still easily the largest party at Holyrood). In 2010, the SNP won 6 MPs; 56 out of 59 in 2015, but fell back to 35 in 2017 (still having the largest number of MPs from Scotland by some way).

ii. The SNP has been able to project a Centre social democratic image, which stood out against the Right social democracy of the British Labour Party. New Labour had embraced imperial wars, particularly the disastrous Iraq War. ‘One Nation’ Labour had embraced conservative unionism, particularly during the ‘Better Together’ campaign. These brought Labour and the Conservatives closer together, a political trajectory already well established with New Labour’s commitment to neo-liberalism – or ‘Blatcherism’. Given the even faster rightwards stampede of the Scottish Labour Party, and their woeful record in the running of many local councils, the SNP did not have to move much to the Left. They just had to occupy some of the old social democratic ground vacated by Labour.

iii. The push from below, shown in the 2012-14 IndyRef Campaign, reinforced the SNP’s social democrat credentials. The party claimed to be the most effective defence in Scotland against Westminster-imposed austerity – although, in practice, this has meant mitigating not defying austerity (e.g. over the bedroom tax following a grassroots campaign). This new emphasis was consolidated after the change in leadership from Alex Salmond to Nicola Sturgeon in November 2014. Like Right social democrat Gordon Brown, Salmond had held considerable illusions in finance sector-led economic growth. Salmond’s vision of an independent Scotland, a ‘Scottish Lion’, joining Ireland and Iceland in the ‘Arc of Prosperity’, was dashed after the 2007-8 Banking Crash, in which the RBoS and BoS played a major part. Since becoming party leader, Sturgeon has adopted a more Centre/Left social democratic stance. The SNP leadership, although still eager to meet the interests of business in Scotland, also wanted to be seen as the party that protects a wider range of class interests, including those workers who once supported Labour.

iv. Over a longer period, the SNP had changed politically in another important respect. The SNP of the 1970s was a populist party, with Right and Left components, mainly reflecting whether it was based in Conservative or Labour dominated areas. Its nationalism was ethnic (as was that of British unionism). Throughout Western Europe and the USA an earlier racial nationalism, based on natural physical features, e.g. skin colour, had been largely replaced by a newer ethnic nationalism based on cultural features, e.g. language, religion, shared history, dress, and diet.

v. However, this ethnic nationalism, once it had largely displaced the earlier discredited racist nationalism, was itself made into a new force for ‘othering’. Right wing ethnic nationalism was very much influenced by Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilisations, with its claims of unbridgeable and antagonistic cultural differences between different groups of people. Thus, instead of hatred of black people, we can now see growing Islamophobia. The impact of this newer ethnic nationalism was so pervasive, that even many fascists began to ditch their emphasis on racial physical features and prioritise the celebration of ethnic cultural traditions. This became one of the significant differences between fascism and neo-fascism. In the wider UK, the neo-fascist BNP began to displace the fascist NF from the later 1980s. Scotland had an early form of neo-fascism in Siol nan Gaidheal. The SNP had to officially proscribe this group in 1981.

vi. However, a more mainstream form of ethnic nationalism also began to replace the earlier racist nationalism, which had been widely accepted in society and even mainstream politics in the relatively recent past. Under New Labour and the Tories attempts were made to define an ethnic British nationalism on the grounds of a shared history and cultural values. However, other identities, such as gender, as well as a person’s class, mean that this history and these cultural values are far from shared and have been contested.

vii. The SNP has subsequently moved beyond this ethnic nationalism to civic nationalism, welcoming all who choose to live in Scotland regardless of ethnicity. The positive effect of this was highlighted when the SNP accepted that all EU residents (as well as 16-18 year olds) could vote in the 2014 IndyRef1. The Conservatives, backed by Labour, both masked their British nationalism under a false ‘international’ unionism. The exclusion of EU residents in the European referendum highlights their continued adherence to ethnic nationalism.

viii. The SNP leadership remain thoroughly constitutional nationalists. They accept the legitimacy of the UK state based on the principle of the sovereignty of the Crown-in-Westminster. In 2005, 4 elected SSP MSPs mounted a protest in Holyrood, in an attempt to uphold its earlier decision to support the right to demonstrate at the Gleneagles G8 conference [i]. The Crown, US and UK security services, including the Met, overrode this decision. The SNP MSPs, not then even in office, rushed to join with Labour, Lib-Dem, Conservative, (and even Green) MSPs to have the SSP MSPs expelled from Holyrood and heavily fined. This SNP subservience to the Crown-in-Westminster and its devolved offspring in Holyrood is a product of their long-term aim of getting a ‘junior managerial buyout’ of the UK’s Scottish ‘branch office’, without any challenge to the Crown Powers. If this proposed ‘buyout’ were to be successful they would be quite happily accept the rUK too.

ix. This ‘Independence-Lite’ stance would, in effect, create a Scottish Free State under the Crown. The SNP leadership hope to achieve this without either the republican revolution or anti-republican counter-revolution, which brought about the Irish Free State. The SNP leadership argues that many people support the queen, so it makes little electoral sense to oppose the monarchy. However, the immediate effect of this acceptance of the monarchy is that any independence referendum is held under the Crown Powers, where ‘Britannia waives the rules’. But, the SNP’s business backers would also like to keep some of those Crown Powers in reserve, for unseen contingencies. Thus their proposed future Scottish state would still be subject to the UK state’s Crown Powers; just as ‘independent’ Australia found out, when the Governor General dismissed Gough Whitlam’s reforming Labour government in 1975.

x. The SNP leadership want their particular political plans for independence to proceed in as orderly a manner as possible, with a minimum of active popular input. That could upset their sought-for business allies. The preferred political means of achieving their aims is to gradually take over as much of the devolved apparatus of the UK state in Scotland as possible. Control of Holyrood and local councils provide the patronage needed to win over Scottish business and professional managerial interests. Forming the Scottish majority of MPs at Westminster opens up the prospect of winning further concessions, particularly in the event of minority governments.

xi. The SNP leadership supports the current global corporate order. They accept its continued domination by the USA, and back the EU as its regional economic upholder. Since 2012, they have officially supported NATO, which militarily protects this imperial order. However, like some of NATO’s member state governments, the SNP leadership can oppose particular US-promoted and UK backed military interventions as not being in the best long-term interests of the global corporate order. Thus, the SNP has opposed wars in Iraq and Syria. But it also supported the Afghanistan and Libya wars, highlighting the limitations of their critical stance.

xii. The SNP leadership appreciate that the UK is a declining global power and that the costs of maintaining the British ruling class’s continued imperial pretensions are increasingly heavy. This is one reason why they oppose Trident renewal. They are strongly opposed to the ‘Singapore with a union jack’ or the ‘Empire2’ trajectories adopted by sections of the British ruling class following the Brexit vote. Thus the SNP can also be seen as backers of those would-be liberal modernisers of the UK state, who want to cutback on its overblown imperial trappings, maintained mainly for the benefit of a reactionary elite. They are prepared to cultivate allies amongst other parties in the UK – Labour, the Greens and Plaid Cymru – to speed up this modernisation process.

xiii. The SNP leadership have been looking for wider support against Brexit, or at least, for the minimisation of its likely very negative impact on the Scottish economy. Brexit threatens continued EU regional aid to Scotland. Brexit undermines Scotland’s potential transition to a new renewables and creative industries based economy. A reinforced UK state would leave large areas of Scotland subject, as before, to the British ruling class’s serial economic ‘looting’ (e.g. coal and North Sea oil), without investing for change, leaving environmental and social devastation in its wake.

xiv. The SNP leadership’s current political strategy has meant a return to their earlier push for more enhanced Devolution. They have tried to find some support from the liberal unionist wing of the British ruling class, which had been responsible for Devolution-all-round. However, this prospect has receded, in the aftermath of the narrow defeat of the Independence Referendum. During the Referendum Campaign a worried British ruling class abandoned its support for creeping Devolution-all-round in favour of a conservative defence of the constitutional status quo. This was linked to a continued but Eurosceptic support for the EU. Cameron and Miliband represented this conservative unionist political approach, although an attempt was made to give this some liberal unionist cover. This cover was soon abandoned once the prospect of Scottish independence had been defeated.

xv. Furthermore, the British ruling class’s retreat from liberal unionism also gave confidence to a thoroughly reactionary unionism (previously confined to Northern Ireland), which linked UKIP and the Tory Right [ii]. They are contemptuous of the existing Devolution settlement, which has provided the basis for the SNP leadership’s constitutional nationalist road to Scottish independence. This Right is decidedly Europhobic. They won a major victory by getting a majority Brexit vote in the 2016 referendum. This ‘No’ majority was achieved on the basis of a largely British ethnic franchise by excluding EU residents, and by not allowing 16-18 year olds to vote.

xvi. Despite the setback the Brexiters faced in the June 2017 general election, when May failed to deliver an overwhelming majority and a ‘strong and stable’ government, the SNP also fell back, losing 21 MPs, mostly to the Tories. This significantly undermined their political clout. The Tories had fought a strongly unionist campaign – ‘No IndyRef2’ and ‘Send Nicola a message’. They were quite prepared to work, openly and behind the scenes, with deeply reactionary forces.

xvii. Nevertheless, despite some rumblings in the SNP ranks after the recent election results, the party’s highly centralised and disciplined nature means that Sturgeon faces little internal challenge and her supporters remain in full control of the party. She can ensure that any Left challenge is limited and that the Right vote for Centre promoted policies at Westminster, e.g. over opposition to the Syrian War and renewal of Trident.

xviii. It is indicative of the priorities of the SNP government that despite the party’s 2015 Westminster general election triumph, Ninewell Hospital porters, workers living in independence and SNP-voting Dundee, still had to take strike action. They faced an intransigent Tayside NHS management, unwilling to remedy years of underpayment. FE lecturers have faced similar problems with public sector managements refusing to honour agreements. These managements feel confident that the SNP government will let them get away with their behaviour. The SNP leadership has a history of fawning before business interests, e.g. the Scottish banks, Murdoch, Trump and Ratcliffe (over his threatened closure of Grangemouth in 2013). In contrast to independence-supporting workers, there has always been a welcome for business lobbyists, even if unionist, at Holyrood.

ix. The SNP government has accepted a top-down managerial market-based approach (borrowed from private industry) to running Scottish services, particularly in education and health. In the process, education has been largely reduced to meeting the training needs of industry, and health to servicing the actual or potential workforce, rather than meeting people’s real needs.

xx. The SNP government still see their primary role as developing a new Scottish ruling class, by winning over influential business figures. These people usually see cutting costs, whether workers’ pay, business taxes and rates, as the most effective means to achieve their aims. Already, some on the Right have been involved in taking action to support Scottish managements against their workforces. Ex-MP Angus Wilson is a key figure in Charlotte Street Partners. They were employed by Colleges Scotland management to help them break the agreement they had made with Scottish lecturers’ union, EIS-FELA. And even many rank and file SNP members have worries about the Right’s possible role, with Fergus Ewing as Energy Minister, in undermining opposition to fracking in Scotland.

xxi. The older ex-79 Left social democratic group has long been absorbed into the party’s social democratic Centre. Any criticisms of the leadership are confined to those who no longer hold governmental office, e.g. Alex Neil and Kenny MacAskill. Furthermore, along with the more populist Jim Sillars, they remain Atlanticists, highlighted by their crucial support for Angus Robertson, when he led the backing for NATO at the 2012 SNP conference. None of the old 79 Group has shown any republican leanings. Alex Neil has attended royal garden parties, whilst Alex Salmond is one of the most pro-monarchy politicians in Scotland.

xxii. The post-2015 emergence of figures like Mhairi Black, Tommy Sheppard and George Kerevan does point to a new Left social democratic current in the SNP. However, in 2015, Sheppard was easily beaten, when he stood for party depute leader. In 2017, he withdrew as candidate for SNP’s Westminster leader. In both cases the Right candidates won.

xxiii. Two key figures on the Right are centrally placed in the SNP leadership. John Swinney (ex-Scottish Amicable strategic planner) is depute party leader. Ian Blackford (investment banker and recipient of a £3000 electoral donation from David Craigen, a Tory hedge fund owner) is the SNP’s Westminster leader. He replaced another Right winger, Angus Robertson. Angus Wilson chairs the SNP’s Growth Commission, which will determine future economic policy of the party. This means the Right are well positioned to push the party into supporting any ‘sacrifices’ they claim will have to be made by others, especially the working class, in order to win their version of Scottish political independence, should the opportunity arise again.

xxiv. If such independence came about then the Right would likely push for major corporate tax cutbacks. Some also support flat rate income taxes (John Swinney) and a major reduction in the proportion of public spending in the economy (Michael Russell). However, as long as it seems necessary for the SNP to put on a more Centre/Left face to win electoral support, the Right is prepared to put some of these policies on the backburner, and publicly support Sturgeon.

xxv. The SNP leadership has devoted a great deal of effort into derailing the more radical possibilities stemming from Scotland’s thwarted democratic revolution. 97% of people had registered and 85% actually voted; support for independence increased from 30% in 2012 to 45% in 2014, after a massive extra-parliamentary campaign. This led to the ‘secession’ of working class Dundee, Glasgow and West Dunbartonshire from the Union. An SNP mass membership drive hoovered up 85,000 new members (a 350% increase). Sturgeon was anointed at a 12,000 strong rally held in November 2014. This was held next door to the 3000 strong Radical Independence Campaign conference, which offered a radical alternative. All this was done so the SNP leadership could gain maximum control over the whole of the Independence Movement, and subordinate it to their constitutional nationalist strategy [iii].

xxvi. However, the continuing use of precarious labour, declining living standards, lack of access to affordable housing, increasing gaps in educational and health provision, and mounting personal debt, mean that many workers in Scotland have become increasingly dissatisfied. In the face of this, the SNP tends to fall back on, “But things are worse in England”. This inadequate response has led many, who looked hopefully to independence in 2014, to drift towards other politics. Some of those atomised workers, no longer in trade unions or supportive community organisations, and lacking in political self-confidence, have looked in despair to a Right-led populist Brexit. Others, especially young people, angry but not yet demoralised, have started to look to Jeremy Corbyn and the Labour Party, and an alternative British Left/Centre social democratic road away from austerity and neo-liberalism.

2. The rise of Jeremy Corbyn and British Left social democracy

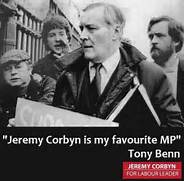

i. The re-emergence of British Left social democracy (not seen since Tony Benn’s challenge in the early 1980s and the Great Miners Strike from 1984-5) has occurred in two phases. The first corresponded to Corbyn’s campaigning and winning two Labour leadership elections – in September 2015, and again in September 2016 after an attempted Right coup in the party. The key feature in this phase was the big increase in Labour Party membership, now at 500,000. This has helped to revive the party’s fortunes and reduce, but not eliminate, the influence of the party’s Right.

ii. The second phase, in the rise of Corbyn, has been his ability, in the June 2017 general election and after, to severely dent the Tory Right’s triumphalist advance, following their Brexit victory in 2016. In April Theresa May called a snap general election, to seek a ‘presidential’ mandate for a ‘hard Brexit’, with minimal input or opposition from Westminster, or its devolved offspring at Holyrood, Cardiff Bay and Stormont. This was to be accompanied by major attacks on the working class to pay for any ‘hard Brexit’, in order to win over those still doubting sections of the British ruling class. The precedent for offloading such costs on to the working class lay in New Labour, Conservative/Lib-Dem and Conservative governments’ austerity offensive following the 2007-8 Banking Crisis. Only this would be done in an even more draconian fashion, now that the ascendant Tory Right had taken on UKIP’s mantle, and won the leadership of the UK government.

iii. Corbyn’s breakthrough occurred very late in the general election campaign. This was highlighted in England by Labour’s very poor results as recently as the local council elections on May 5th. Labour lost 146 seats, whilst the Conservatives gained 313, at the expense of Labour, UKIP and the Lib-Dems. The Conservatives also won the mayors of West Midlands and Tees Valley. (Scotland and Wales will be addressed later)

iv. Corbyn’s surge, much of it in the last few days before the election on June 8th, was due to Tory hubris following the Brexit victory and their big advances in the local council elections. Corbyn successfully countered this by motivating his mainly young new supporters with a Manifesto, which, for the first time in recent Labour history, addressed some of their needs. Furthermore, Corbyn’s campaigners (like those in the 2012-14 Scottish IndyRef campaign) knew there would be no sympathy from the mainstream media, so they took to the streets, registering mainly young voters, and holding very well attended rallies. They began to whittle away May’s early commanding lead.

v. The Left/Centre social democratic meat of Labour’s Manifesto was accepted by all but the most unreconstructed neo-Blairites in the Labour Party. Those people even unwittingly played into Corbyn’s hands by leaking the Manifesto to the press. The less histrionic section of the Labour Right was reassured by its success in sandwiching the Manifesto’s key economic and social policies between opposition to any future Scottish independence referendum and support for Trident renewal. This showed that, even under Corbyn’s leadership, Labour would still officially recognise the British ruling class’s existing UK constitutional and imperial order. A jittery ruling class was given some crumbs of comfort. The Labour Right, cowed but not defeated, could also still help undermine Corbyn, if the political situation changed.

vi. However, Corbyn also managed to pull off his own clever piece of political triangulation. By supporting May, in the crucial Westminster votes over Brexit (e.g. over invoking Article 50), Corbyn neutralised Brexit as the major issue to attack him on. The Right-dominated media turned instead to Corbyn’s ‘Loony Left’ policies, which turned out to be more far popular than the dismissive Right wing media had thought. Furthermore, by supporting the abolition of student fees, he also neutralised any defection of his own young supporters, mainly Remainers, to the Lib-Dems. Labour’s winning of student votes in the Sheffield Hallam constituency highlighted the success of this tactic. Here Labour ousted Nick Clegg, the architect of the Lib-Dems’ own climb down over student fees, when in coalition with Cameron’s Conservatives from 2010-15.

vii. Corbyn’s support for Brexit was also designed to win back Labour defectors from UKIP and the Tories. Although Labour took 25 seats from the Tories in England (winning their biggest increase in votes in university towns), the Tories still took 6 seats from Labour – Copeland, Derbyshire North East, Mansfield, Middlesbrough South, Stoke-on-Trent and Walsall North – benefitting from the collapse of UKIP. These are all very longstanding Labour seats. This highlights the continued Right pull shown in the earlier rise of UKIP and the strong Brexit vote amongst atomised working class communities, ravished by the closure of traditional industries, and looking outside their own ranks for saviours and scapegoats.

viii. Clearly those recently UKIP-supporting but previously Labour voters, mainly found in the old devastated industrial areas in the North, Midlands and South Wales, and pulled into the Right’s Brexit anti-migrant worker and asylum seeker slipstream, are still on Corbyn’s mind. The continued pull of politics to the Right has been shown in his stance over Brexit, siding with May’s Tories over crucial votes, and particularly in his ambiguous stance over the defence of EU migrant rights.

3. The prospects for Corbyn and Left social democracy when handling economic and social issues

i. There are many of obstacles when it comes to a prospective Corbyn-led government implementing its Manifesto. It remains the case that the Labour Party bureaucracy, the majority of its MPs and councillors are on the Right. However, for the immediate future, any open challenge by the Labour Right appears to have receded, after Corbyn’s unexpectedly good showing at the general election.

ii. It is not just the Labour Right, though, which is reining in Corbyn’s own Left social democratic politics. Len McCluskey was a key figure in ensuring the Labour Manifesto commitment to the renewal of Trident. McCluskey is a recent convert to supporting Corbyn, having opposed his close ally, John McDonnell, in the 2010 Labour leadership challenge, in favour of ‘One Nation’, Miliband. McCluskey has a record of Left posturing and mounting token strikes and protests before climbing down. He did this over the November 30th, 2011 Pension Strike of public service workers, and in 2013 over Grangemouth oil refinery workers, who became victims of his political manoeuvring in the Falkirk Labour Party.

iii. What McCluskey wants, above all else, is to restore the role of trade union bureaucrats within the Labour Party. As the highly paid general secretary of the largest trade union in the UK (also extending to the 26 Counties), and in effective control of the appointment of many officials, he envisages wielding considerably enhanced political power. What McCluskey certainly does not want is any independent Left in the Labour Party putting its own demands on Corbyn or a future Labour government. Should Labour take office, then McCluskey and other trade union leaders can be expected to use their bureaucratic power to enforce whatever ‘sacrifices’ are required of their members to prop up Corbyn; just as the Left trade union bureaucrats, High Scanlon (AEU) and Jack Jones MBE (TGWU), did for the Wilson and Callaghan governments under the Social Contract (or ‘Contrick’ as it became termed by union militants) between 1974-9.

iv. To this end, McCluskey and Corbyn will be reassured by the development of Momentum. Momentum was formed to win a Corbyn Labour leadership and campaign for a Labour Westminster victory. Many within Momentum want to subordinate the Parliamentary Party to the party membership. However, Momentum’s chair, and effective leader, John Lansman, sees the organisation as being a collective cheerleader for Corbyn. To a considerable degree he goes along with Corbyn’s continued accommodation with the Labour Right, which they both see as necessary for Labour’s further electoral advance. This was highlighted in Lansman’s support for the ousting of Jackie Walker as vice-chair of Momentum, under internal and external pressure from the Right.

v. Although Momentum does not have the political coherence to match the Campaign for Labour Democracy in Benn’s day, it is still likely that the Left will increase its influence in the party at the expense of the Right through ad hoc local challenges. With the unsettled political situation, following the mauling of May – “a dead woman walking” – during and after the general election, and the political impact of the Grenfell Flats Disaster, Corbyn could yet form a Labour-led government. The real problems would begin when Corbyn took office.

vi. Corbyn and his supporters are aware of the opposition he is likely to face from the Tories and the Right wing media, when it comes to implementing the economic and social measures in the Labour Manifesto. To provide Corbyn with support, the Left inside and outside the Labour Party are already planning demonstrations, and looking forward to the possibilities of strike action (underestimating the likely opposition of the trade union bureaucrats).

vii. Yet Corbyn has not put forward any plans to deal with the power of the City of London, which has long held a stranglehold over the Treasury, and consequently over economic and social policy. The City ensured that Gordon Brown and Alistair Darling buckled to its demands (not that they needed much persuading!) and that the working class has had to pay for the 2007-8 Banking Crisis.

viii. Although the possibilities of The City creating an economic crisis to directly impose a business-led caretaker government could not be ruled out, their preferred option would more likely be to get the Labour Right, supported by the Centre, to ditch Corbyn and the Left. This would be similar to what happened in 1983 when the Bank of France was able to provoke a breach between the Socialist Party under President, Francois Mitterand, and the Communist Party ministers, in a shared government, formed in 1981. It had been elected under a Common Programme based on neo-Keynesian policies. After ousting the CP ministers, Mitterand adopted the ‘tournant de la rigeur’, or the austerity turn. Should Tony Benn have triumphed in the Labour Party with his Labour Left/CPGB supported Alternative Economic Strategy, and become Prime Minister in the 1980s, he would have faced the same pressures, with likely the same result.

ix. More recently, in Greece, we have seen the Left populist Syriza government (with significant Left social democratic support) elected on a considerably more radical Manifesto than Labour’s (albeit still on an essentially neo-Keynesian economic basis). However, rather than being ousted from office, Syriza leader, Alexis Tsipras, following a spectacular climb down, took direct responsibility for implementing the Troika’s austerity programme.

4. The limitations of Corbyn and Left social democracy when dealing with matters of state.

A. Brexit

i. Although Corbyn and the Labour Left appear more confident when it comes to putting over their economic and social policies, when it comes to matters of state, they are on much less sure grounds. Like Right social democrats, the Left tacitly accepts the existing UK constitutional order, or tails the constitutional policies of whichever section of the British ruing class, or aspiring ruling class, it hopes will advance its immediate interests. To explain their lack of support for independent working class politics with regard to the state, social democrats often argue that the working class is only really interested in ‘bread and butter’ issues.

ii. Thus, the Left are ill-prepared for any state actions done under the cover of the Crown Powers. Corbyn’s public acceptance of the monarchy, the Privy Council and the House of Lords (by appointing Shami Chakrabati), highlights this longstanding weakness of British Left social democracy with regard to the limitations imposed by the UK state.

iii. When it comes to matters of state, a Corbyn led government would inherit two major problems currently confronting the British ruling class and the UK – Brexit and the unresolved National Question in Ireland and Scotland. In the short term, Brexit seems the most pressing, but this too is linked to the National Question, with the future of Northern Ireland, in particular, at the very centre of negotiations. It may well be on issues such as these that a Corbyn-led government could first find itself politically paralysed and then toppled. Or it could be Corbyn’s capitulation in the face of another US promoted imperial war. His acceptance of NATO and his backtracking on earlier support for Palestinian self-determination, in the face of an Israeli state, Labour Friends of Israel, Labour Right, Tory, Lib-Dem and right wing media offensive, reveal his weaknesses in the face of imperial pressure.

iv. Corbyn’s own weakness with regard to Brexit has already been shown. On July 5th, Nicholas Watt, speaking on BBC Newsnight, said, “I did speak to one senior {Tory} Brexiteer who is absolutely confident that Brexit will happen if only for one very simple reason – Labour divisions mean that the legislation paving the way for Brexit will get through Parliament” [iv]. In other words, in order placate anti-migrant sentiment amongst wavering Labour supporters in the traditional industrial heartlands, Corbyn backs May when it comes to crucial Brexit votes.

v. Therefore, if the wheels are currently coming off May’s own proposed ‘hard Brexit’, despite her frequent resort to a Right populist anti-migrant stance, migrant workers from the EU will not necessarily be any more secure under a Corbyn-led Brexit. You can get some indication of this from the interview where he said, “If you talk to the people of West Bromwich, they will tell you that {freedom of movement} is the reason they voted to leave the EU in very large numbers [v].” In other words, Corbyn could bow to anti-migrant sentiment he has found amongst Brexiters and indeed within his own party. This includes people like leading Brexiter and UKIP-Lite, ex-MP, Tom Harris.

vi. Despite the clear differences between the official Remainers and the official Leavers over Brexit, both were united in wanting increased control over migrant labour. The opening of detention centres like Thamesmead and Dungarvel was started under New Labour. The attempt to construct an ethnic (i.e. cultural) basis for attaining officially recognised British citizen (read subject) status began under Gordon Brown and was continued under Michael Gove. Labour did not oppose the British ethnic restrictions imposed on the franchise for the 2016 EU referendum.

vii. The first demand of Eurosceptic Cameron was to try to limit the welfare rights of new EU immigrants. This special treatment represented an extension of the ‘exemptions’ principle, which Thatcher, Major, Blair, Brown and Cameron already supported in relation to the EU’s Social Chapter. Cameron hoped that by appealing to the Right wing governments in Eastern Europe, which had openly defied the EU over the dispersal of asylum seekers, he would be able to put pressure on its key leaders. Along with the rise of wider anti-asylum seeker sentiment in the EU, he thought that this could create the political momentum to further undermine the free movement of people within the EU.

viii. Furthermore, the Tories, like the populist-led eastern European governments, had already been to the forefront of attacks on a long settled minority group within the UK and EU – Travellers and Gypsies. This was highlighted by the evictions of Travellers from land they owned at Dale Farm in Basildon, Essex in 2011. So freedom of movement, and even of property use for certain ‘outsiders’, had already been curtailed in the UK, without any opposition from the EU.

ix. Tory Home Secretary, Theresa May, then a Remainer, was responsible for the introduction of the draconian 2014 and 2016 Immigration Acts. These virtually eliminated the welfare rights of non-EU migrants. Labour did not oppose these Acts, which contributed to the creation of a more highly segmented workforce. At the bottom are ‘illegals’ without any work or residency rights. They are subjected to harassment by state officials and police, and to super-exploitation by gangmeisters and sex traffickers. Denied other options, some of these ‘illegals’ do become involved in these and other criminal activities, e.g. drug dealing. Although these are all illegal businesses, their profits are readily laundered by mainstream banks, which globally recycle huge amounts of criminal funds (as well, of course, the vast amounts to be made from tax evasion).

x. Above the ‘illegals’ in the hierarchy, are different levels of labour – unskilled, semi-skilled, skilled, professional and managerial – often characterised by different citizenship status, residency rights, work contracts, and pay and conditions. At the very top of the hierarchy are those non-British business executives, Gulf oil sheiks with their domestic slaves, and Russian gangster capitalists, who move freely, buying businesses or shares in businesses in the UK, expensive houses in London or estates in the country, as well as football clubs and art galleries. When not openly courted by British governments, they can ‘buy’ Westminster politicians. Significantly, the City of London is already seeking its own deal with the EU, independent of the UK government, to allow the easy movement of business executives. Of course, May’s government will warmly sanction this unofficial action, unlike unofficial attempts to defend migrant workers. Brexit only means Brexit for some.

xi. A key aspect of the recent Immigration Acts is to involve non-government personnel in the policing of migration. Landlords, health, teachers and social workers and others have to monitor prospective tenants, users of health, education and social work services. There are penalties for landlords who provide accommodation for ‘illegals’. Not surprisingly, landlords err on the side of caution and refuse tenancies to people who might be ‘illegal’, merely on the grounds of their appearance. The 2015 Counter-Terrorism and Security Act takes process this considerably further. Through the so-called Prevent strategy, many public sector workers are being drawn into state attempts to prevent ‘radicalisation’ (targeting people from as young as the age of three). As with the 1974 Prevention of Terrorism Act designed to deal with the situation in Ireland, a primary purpose is to silence all opposition to government policies of military repression (in Ireland in 1974 and in the Middle East and Afghanistan today). The earlier promotion of anti-Irish racism takes the form of Islamophobia today.

xii. Although official Remainers – Conservative and Labour – have been united with Leavers – official and unofficial – in undermining migrant and asylum seeker rights (and promoting Islamophobia), the Leavers wanted to go much further and make EU migrants living in the UK subject to the draconian 2014 and 2016 Immigration Acts. This would create a massive increase in workers with far more limited residency and welfare rights and many more ‘illegals’. This would also massively divide the working class in the UK, and provide greatly increased scope for stepped up racism, both officially by the state and state-contracted private security agencies, and unofficially by the Far Right. The effect of this would be to drive down the pay and conditions of all workers. This, and the bonfire of other regulations (e.g. health and safety and environmental safeguards), was the mouth-watering prospect with which the Right hoped to win over the majority of the British ruling class to Brexit.

xiii. The 2014 and 2016 Immigration Acts have to be seen alongside Ian Duncan Smith’s 2012 Welfare Reform Act, again not opposed by Labour at the time. This represents another attempt to create a segmented workforce, with access to welfare subjected to a harsh disciplinary regime, administered by private agencies whose primary aim is profit making. Here, the equivalent of ‘illegals’ are those, particularly the disabled, who are stripped of benefit rights and forced into dependence on food banks, other charities, or sometimes driven to suicide. Immediately above these people in the welfare hierarchy are those in low paid, often precarious, jobs, who need welfare benefits to augment their incomes and obtain access to housing. Furthermore, earlier attacks on welfare users were accompanied by government attempts to draw non-government personnel, e.g. neighbours, into reporting anonymously about perceived fraud. The more recent Immigration and Counter-Terrorism and Security Acts have developed this much further, by placing a legal requirement on many public sector workers be part of a government surveillance exercise.

xiv. It is becoming clearer that the UK state wishes to create a more segmented workforce, through differential residency and welfare access. Responsibility for this is divided between state-run and privately contracted security agencies. To fill the recognised gaps in the labour market a new ‘gastarbeiter’ system is planned to manage migrant labour. This would also enable British employers to turn much more to cheaper contracted labour from outside the EU. The UK state is also able to control and monitor the movement of migrants and benefits applicants, through its requirement that people constantly register themselves and fill in forms to access any rights or benefits, and through the all-pervasive surveillance of CCTV.

xv. Thus Corbyn’s decided ambiguity over migrant rights can also be seen as contributing to the employers’ desire for greater management and control over migration. Shadow Business Secretary, Clive Lewis said free movement of workers “hasn’t worked for a lot of people”, while Shadow Brexit Secretary Keir Starmer said the right to live and work in any EU country – “was no longer sustainable”, and called for “the reasonable management of migration” [vi].

xvi. Corbyn and most in the Labour leadership would be opposed to the open racism of the Right wing media, the Tory Right and Far Right wing, which would inevitably accompany such closely state-managed migration. However, for those migrants subjected to such treatment, the mainstream Right and the Far Right, although a real threat, would be secondary in the impact on their everyday lives to the activities of official state (e.g. immigration officials and police) and state-contracted private security and welfare companies.

xvii. Social liberals can become quite vocal in their opposition to the Right and Far Right, but tend to remain much quieter about the impact of the agents of the state. Corbyn’s social democratic politics, which largely accept the nature of the UK state, reflects this silence, when it comes to the implications of implementing a more comprehensive state-managed migration system.

xviii. And to provide cover for such silence, we have the CPB, along with its Labour Left allies (particularly those in trade union bureaucrat positions). These people are advocates of that chimera – ‘non-racist’ immigration controls. This notion gives succour to any state attempt to control and manage migration by its own officials and or through contracted private agencies. By means of their everyday practice, they implement British chauvinist and racist discrimination, which does not have the public visibility of the activities of the Right and Far Right. It is not surprising that detention centre security agents, police and others officially responsible for handling migrants and asylum seekers often have such poor records, and usually support the Right and in some cases the Far Right. The number of migrant deaths in police custody (e.g. Sheku Bayou in Kirkcaldy) is just one indicator of this.

xix. Corbyn’s tail-ending of May over Brexit has also provided the first new opening for the Labour Right. They still follow the same Eurosceptic line as Blair and Cameron, opposing further unification of the EU, supporting British ‘exemptions’ and greater state control of migration. However, the Labour Right have sensed that some sections of the British ruling class have not been fully won over to an acceptance of Brexit, particularly the hard Brexit supported by May. Her promise of a ‘strong and stable’ leadership, with little opposition, formed the basis of her attempt to win over those still doubting sections of the British ruling class. Many are also not keen on her dependence upon the obdurate DUP for support.

xx. Chukka Umunna is playing the most skilful game on the Labour Right. After the general election he indicated that there would be no immediate Right challenge to Corbyn as party leader. However, Umanna has carefully chosen opposition to May’s ‘hard Brexit’ as an issue to build up wider support in the future. Unlike the Lib-Dems, Umanna is no Europhile, and has in the past supported Blue Labour, one of the furthest Right groups in Labour (along with business financed and uber-Blaitrite Progress and Israeli state-backed Labour Friends of Israel). Umanna is on record as having said that, “If continuation of the free movement is the price of single market membership then clearly we couldn’t remain in the single market [vii].” In adopting this stance he is little different from Corbyn, who has also said that, “Labour is not wedded to freedom of movement for EU citizens as a point of principle [viii].”

xxi. Nevertheless, on June 28th, Umanna’s pro-Single Market amendment to May’s ‘hard Brexit’ Queen’s Speech proposals, was rightly seen as a challenge to Corbyn too. Furthermore, embarrassingly for Corbyn, on this occasion it was Umanna, who was breaking Labour Parliamentary Party discipline in order to oppose the Tories. Umanna would be in little doubt about his immediate political fate in defying party discipline, after Corbyn’s perceived general election triumph. Umanna, though, was looking to the future, and the political possibilities opening up if the Brexit negotiations with the EU leaders go pear-shaped. In the vote, Umanna won the support of 49 Labour rebels, mainly fellow Eurosceptic Remainers, and 12 Lib-Dem Europhiles. However, he also won the support of 34 SNP, 4 Plaid Cymru and 1 Green MP. These three parties have better post-2010 Westminster voting records than Labour, even under Corbyn.

xxii. If the economic crisis deepens and things start to seriously unravel, then the prospect of key sections of the British ruling class pushing for a National Government, formed from Labour, Conservative and Lib-Dem Remainers, can not be ruled out. Less likely, but not beyond the realms of possibility in the current highly unstable international political situation, is the creation of a new Centre populist party, along the lines of Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche (formed as recently as April 2016, and taking office in May 2017). Umanna would be well positioned in either of these political scenarios.

xxiii. Even the TUC urged Corbyn to back a Single Market to protect jobs, whilst also showing its concerns over the potential for a bonfire of Social Chapter protections after any Brexit, especially if a Tory government manages to hold together. During the Euro-referendum campaign, Corbyn, although critical of the EU, had followed the TUC’s pro-Remain line. During the grim years under Thatcher, the TUC had ditched its earlier opposition to the EEC, seeing the EU as offering at least some social and economic protection through its Social Chapter provision and regional funding.

xxiv. In defying the TUC (with the exception of the pro-Brexit Bakers Union and the still Labour unaffiliated RMT), Corbyn was looking, on June 28th, to those one-time pro-USSR CPGBers, now pro-Putin’s Russia CPBers, along with their Labour Left supporters. They have long been part of the Europhobic camp. This section of Corbyn’s supporters is quite prepared to look far beyond the ranks of organised Labour, now much diminished anyhow. Corbyn adviser, Seamus Milne and Corbyn supporter, John Trickett MP, have argued explicitly for Corbyn to adopt a Left populist stance. The problem with populism is its easy switch from Left to Right. This was shown by Europhobe, wannabe Labour member, George Galloway’s open embrace of Nigel Farage during the Euro-referendum campaign. (At an international level, the post-1991 Communist Parties’ continued pro-Russia stance has led to the formation of Red-Brown alliances in Eastern Europe, whilst Putin openly courts the Far Right in Europe).

xxv. Thus Corbyn’s current ability to appeal to Remainers and Leavers, either young people or cynical MPs concerned for their careers, can work to an extent, whilst he remains in opposition. But, if Labour were to take office, the contradictions would become apparent as soon as they took over responsibility for the British Brexit negotiations. Indeed they might surface even before that, if Labour needed the support of other parties to form a government.

B. The National Question

i. The other area where Corbyn faces a considerable problem is addressing the National Question. Although there are some who argue that after the defeat of the Scottish independence bid in 2014, the British focus provided by Brexit since 2016, the setback for the SNP and the containment of Plaid Cymru within Welsh-speaking Wales during the June 2017 general election, and the electoral advance of Labour in England (+21 seats), Scotland (+6 seats) and Wales (+3 seats); the National Question has now been marginalised or contained, and a British social democratic road has been reopened.

ii. However, even the most starry-eyed Labour supporters understand that the National Question has not disappeared in Northern Ireland. Some have called for Sinn Fein to abandon its abstentionist position to increase a social democratic and Labour-supporting contingent at Westminster – particularly with the DUP propping up the Tories. In this they can also make use of Corbyn and McDonnell’s own much earlier open support for Sinn Fein, which, however, they are now distancing themselves from.

iii. Those thinking that the National Question is unimportant can be found amongst Labour supporters who see the existing UK state as providing a quite adequate vehicle for their proposed social democratic reforms. They often look nostalgically back to the ‘Spirit of 45’ or 1974-6. They have little notion of just how the reactionary the UK state is, with its draconian Crown Powers allowing the British ruling class to block any substantial reforms in a period of economic and political crises.

iv. Furthermore, the unionist nature of the UK state, underwritten by the sovereignty of the Crown-in-Westminster, is another major obstacle to reform. This is why the British ruling class is very aware of the significance of the National Question and the need for its successful management in maintaining the unity of the UK state. Sections of this class have developed different strategies – conservative, liberal and reactionary unionist – to help them achieve this. Labour, particularly its Left wing has tended to opt for liberal unionist Home Rule or devolutionary solutions to the National Question, to maintain the unity of this state.

v. Occasionally Labour goes as far as verbal support for federalism, by which they understand advanced Home Rule or Devo-Max. Properly constituted federalism is impossible within a state based on supremacy of the Crown-in-Westminster that denies the right of national self-determination. The UK’s constitutional set-up always maintains the right of Westminster to over-ride any subordinate assemblies, even in areas where they are normally deemed to be competent.

vi. In the face of national democratic challenges, Labour’s Right wing (but also some on its Left) has sometimes supported conservative unionist, and even reactionary unionist defence of the UK constitutional order – especially in Ireland/Northern Ireland. County Antrim-born Kate Hoey, Labour MP for Vauxhall and Countryside Alliance supporter, went as far as campaigning for the Ulster Unionist Party in the 2010 general election, when they were in an electoral pact with the Conservatives. But she did provide her signature to let Corbyn stand for the Labour leader. She is a very keen Brexit supporter, campaigning alongside Nigel Farage proclaiming, “We want our country back.” Such is the politics of populism. But hopefully even Corbyn realises she would not make a good Northern Irish Secretary!

vii. It is this combination of hostility, indifference, and adaptation to ruling class varieties of unionism within the Labour Party, that Corbyn would have to deal with, when addressing the pressing National Questions in Ireland and Scotland, and the less pressing but nevertheless potential National Question in Wales.

a. Conservative, liberal and unionist attempts to maintain the unity of the UK state since the nineteenth century

i. When addressing the National Question, it is necessary to understand the unionist nature of the UK state, and how it acts as a block to reform. The UK state is not a unitary British state, but a Union of constituent nations (or part nation in the case of Northern Ireland) – England and Scotland from 1707, and Ireland from 1801-1922, Northern Ireland from 1922, and Wales from 1998 (when it was finally politically recognised as a constituent nation, having been incorporated into the unitary English state in 1536) [ix].

ii. This Union has been developed to give national self-determination to the component sections of British ruling class – Scottish-British, Irish-British, ‘Ulster’-British and Welsh-British. The promotion of these hybrid forms of Britishness has also been used to mobilise the subordinate classes in the component parts of the UK behind this state [x]. To do this more effectively there have been conservative, liberal, Labour, reactionary and even marxist British unionist parties and political organisations, to ensure that politics are constrained by an acceptance of the UK state as the framework for their activities. Although the British ruling class has always preferred the Conservative (and Unionist) Party, other Union-accepting parties, e.g. Liberals and Labour, can sometimes provide emergency ‘fire-and-theft’ back-up, in the face of national democratic challenges.

iii. So far though, the British marxist unionist organisations (e.g. the SDF /BSP- the originator of ‘the British road to socialism’ – the CPGB, the CPB, the pre-2012 SWP, the pre-1998 Militant (now Socialist Party) and the Alliance for Workers Liberty have not been called upon directly, but have acted as props to the Labour unionists, e.g. in opposing the 1916 Rising during the First World War, Scottish Home Rule after the Second World War, Scottish and Welsh Devolution in 1979, and Scottish independence from 2012 [xi].

iv. The various hybrid sections of the British ruling class allied under the Union to defend their class interests. This was done initially against French-backed Jacobite challenges, then later French-backed republican and Napoleonic imperial challenges. They wanted to benefit jointly from British imperial plunder and longer term exploitation. Along with the House of Lords, this Union has provided particular sections of the ruling class with the means to get assistance from their class cousins in other parts of the UK whenever needed. This is done to impose their own narrow class interests, or to deny the wishes of the majority in their particular constituent unit of the state.

v. Thus, the suspension of legal rights in the constituent nation of Ireland, along with the use of non-Irish military forces to suppress domestic discontent was often resorted to in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This was done to defend the class interests of the Ascendancy landlord class, later extended also to the north-east Ulster industrialists. The House of Lords vetoed land reform measures that had majority support in Ireland, Scotland and Wales, in order to protect the local landlord class in these constituent nations. In 1919, regiments and tanks from England were sent to Glasgow to suppress the 40 Hours Strike. In 1969, the Ulster Unionists were able to get the backing of British troops to defend their sectarian statelet. In 1998, the poll tax was tested out first in Scotland in 1998, despite Thatcher’s Tories being in a minority here. In 2003, Tony Blair used Scottish Labour MPs to provide a narrow majority to impose foundation hospitals on England.

vi. More recently, May has made use of the House of Lords to get Ian Duncan into Westminster, after he had been just rejected by the electorate in Perth and North Perthshire in June. She wanted him to become depute Scottish leader to David Mundell, which lets us know what May thinks of her 12 new recently elected Scottish MPs! Danielle Rowley MP has just failed to be elected chair of the Scottish Parliamentary Labour Party, because there are now more Scottish Labour lords than Scottish Labour MPs at Westminster. They voted instead for ultra-unionist Tory collaborator, Ian Murray.

vii. In the earlier days of the Union, administrative devolution was considered sufficient to run the affairs of Scotland, Ireland and Wales. When challenged by liberal unionists campaigning for political devolution (then called Home Rule) at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, opposition to this became associated with conservative unionism. In the later nineteenth century, the UK was increasingly challenged as world leader by other imperial powers, particularly Russia, France, Prussia/Germany, and later the USA. This led the conservative and reactionary sections of the British ruling class to dig in their heels to oppose constitutional reform. They mobilised every anti-democratic force in the UK state – the House of Lords, the judiciary, the police, the army, plus the extra constitutional UVF – during the struggle to oppose 1913-4 Third Irish Home Rule Bill, which was seen by them as weakening the UK state.

viii. A long term and unintended consequence of this intransigence was the loss, following the 1916-23 International Revolutionary Wave, of 26 Counties of Ireland in 1922. But not before the UK state was able to impose Partition, with an Irish Free State under the Crown, and what became the political slum of a devolved 6 Counties Stormont statelet. To achieve this, the UK state armed the anti-Republican, pro-Treaty forces in the Irish Civil War, and sanctioned Orange pogroms in Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland replaced Ireland as a constituent unit of the UK. Official Irish-Britishness disappeared to be replaced by a narrower ‘Ulster’-Britishness.

ix. After the end of this International Revolutionary Wave, with the containment of the situation in Ireland, and the death of John Maclean in Scotland, the National Question disappeared from the UK’s political agenda. However, towards the end of, and immediately following the Second World War, a strongly supported Scottish Home Rule movement did re-emerge. The new Labour government opposed this though. It ditched earlier Labour (particularly ILP) support for Scottish Home Rule and became strongly wedded to a conservative unionist approach to the UK constitution; just as it remained committed to the maintenance of as much of the British Empire as could still be retained. Instead Labour, in the ‘Spirit of 45’ (following its participation in the wartime coalition), opted to build the UK as social monarchist and imperialist welfare state, following the (Liberal Lord) Beveridge Report of 1943, and celebrated in the 1951 Festival of Britain.

x. The continued decline of traditional industry in Scotland and Wales, the negative impact of the massive inequality in land ownership in rural Scotland, and the growing disparity in incomes between Scotland and Wales on the one hand, and London and the South East on the other, contributed to a new impetus for political devolution for Scotland and Wales in the late 1960s and 1970s. This was shown by the rise of the constitutional nationalist SNP and Plaid Cymru. That led the then dominant liberal wing of the British ruling class to once more contemplate political devolution. The Labour government introduced Scottish and Welsh Home Rule Bills in 1979.

xi. However, by that time, a growing international economic crisis had persuaded the majority of the British ruling class to abandon any liberal constitutional experiments and batten down the hatches of UK Ltd. This led to a split between liberal and conservative unionists in the Labour government and the wider party. The conservative unionists joined with the rising Tory Right and succeeded in thwarting Scottish and Welsh political devolution. This brought down the Labour government, paving the way for the brutal Thatcher years. Neil Kinnock’s sell-out of the miners in 1984-5 had already been anticipated in his role as a conservative unionist opponent of Welsh Devolution between 1977-9. He bowed to ruling class pressure, when ‘the enemy within’ threatened the UK state.

xii. In the lead up to the 1979 Scottish and Welsh devolution referenda, the Labour government’s proposals also had the support of the SNP and Plaid Cymru. But, since their challenge was of a very mild and thoroughly constitutionalist nature, the UK state did not have to resort to its more draconian Crown Powers. It confined its activities to the suppression of key economic documentation, the use of the ‘apolitical’ queen to let her ‘concerns’ be known in her Christmas Speech, resort to agent provocateurs on the Scottish nationalist fringe, and mounting a simulated ‘anti-terrorist’ military and naval practice exercise. However, the main work in seeing off Devolution was done by the mainstream conservative unionists, both Labour and Tory.

xiii. This was in marked contrast to Northern Ireland, where the UK government resorted to military backing for the Ulster Unionists to suppress the Civil Rights Movement. This was highlighted by Bloody Sunday in Derry in 1971. This led to the re-emergence of the revolutionary nationalist Irish Republican Movement, whose activities were in defiance of the UK constitution. In 1972, the UK Conservative government stood down the devolved Stormont administration the better to take full control of defeating this new challenge. Initially, under the 1973 Sunningdale Agreement, some attempt was made to set-up a new reformed power-sharing Stormont, with a few liberal unionists and the constitutional nationalist SDLP. However, this was seen off in 1975 (after Labour had been elected) by a reactionary Loyalist offensive, which united the rejectionist wing of the Ulster Unionists, the DUP, the semi-fascist Vanguard Party, the Orange Order and the Loyalist paramilitaries, including the UDA, legally recognised by the UK state until 1981. Behind-the-scenes, the British security forces assisted the UVF in the murder of 33 civilians in Dublin and Monaghan in 1974, to frighten off the Irish government from giving any support to their state-recognised citizens in the North.

xiv. Under Northern Irish Secretary, Roy ‘Stone’ Mason, Labour followed this by mounting its Criminalisation Offensive. This was mainly done by resort to the Crown Powers, the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act having already been passed in 1973 under the Conservatives. The UK state made use of Loyalist death squads, SAS shoot-to-kill, juryless Diplock Courts and internment without trial. Successive Northern Irish Secretaries prioritised military and security service activities. After 1979, the Criminalisation Offensive was stepped up under the Tories.

xv. UK Direct Rule, accompanied by Northern Irish administrative devolution, proved to be no more liberal than the suspended Orange Stormont regime. No wonder the Civil Rights Movement (for equal rights throughout the UK) disappeared rapidly. However, the level of repression resorted to in Northern Ireland failed to suppress the Republican Movement. It mounted a combined military and political counter-offensive after the Hunger Strikes in 1981. It proved impossible to contain and marginalise the National Question in Ireland, in the manner which been achieved between 1922 and 1972; or which initially appeared to have been achieved after 1979 in Scotland and Wales. The dire economic and social effects of the deindustrialisation of Scotland and Wales, and the testing out of reactionary laws, such as the poll tax in Scotland, contributed to the reappearance of the National Question here too.

xvi. Because of its failure to see off the Republican Movement, a ‘New Unionist’ strategy was developed for the British ruling class, once Major had replaced Thatcher. The first indication of this was the 1993 Downing Street Declaration. This represented a new attempt to bring about a power-sharing Stormont, this time (unlike Sunningdale) with the active involvement of the Republican Movement. As it turned out, a Conservative government, dependent on Ulster Unionist support at Westminster, could not deliver. It was left to the incoming 1997 New Labour government to further develop and implement this ‘New Unionist’ strategy.

xvii. To woo the Republican Movement, the 1998 Good Friday Agreement provided a guarantee for nationalist representation in a new devolved Stormont government. In effect, this meant that Partition was moved from the Border (which became quite open) to the make-up of the new Stormont administration, with its officially recognised Unionist and Nationalist blocs. Sinn Fein has tried pushed for ‘parity of esteem’. Stormont has opened up considerable career prospects for middle class nationalists. In the process, the revolutionary nationalist Republican Movement has given way to the constitutional nationalist Sinn Fein.

xviii. However, whilst claiming a neutral arbiter status between Unionists and Nationalists, Blair and all subsequent British government leaders have publicly indicated their preference for the Union. The latest deal between May and the DUP means that the government has abandoned any pretence of neutrality, with the DUP now forming part of the UK-wide reactionary unionist alliance.

xvix. Sinn Fein sees its future prospects as based on upholding the new partitioned Stormont, until the Northern Ireland Secretary approves a Border Poll, leading to 6 Counties Ireland (Northern Ireland) voting to join 26 Counties Ireland. Although not openly stated, this is usually understood as happening in the relatively near future, when the demographics have turned to the Nationalists’ advantage. In the meantime, all sorts of retreats have had to be accepted in the face of DUP and Loyalist intransigence, and a UK government more determined after the 2007-8 Crash to impose austerity.

xx. Hence in 2015, after much huffing and puffing, Sinn Fein, prompted by local trade union bureaucrats, signed up to Fresh Start – The Stormont Agreement and the Implementation Plan. The UK government is manipulating Sinn Fein’s desire to keep Stormont running in order to impose austerity. However, in the absence of a mass democratic all-Ireland alternative, a return to Direct Rule is likely to be no more progressive than when the UK government suspended Stormont in 1973. Such a scenario could also see a stepping up of Loyalist violence and dissident Republican militarism.

xxi. Until very recently, British governments would probably have preferred it if a new liberal unionism could take root in Northern Ireland. However, reactionary unionism has retained its political domination. The DUP has made electoral deals with the conservative unionist OUP, the more reactionary Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) and Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) (as well as UKIP). In the process the DUP has eaten into their electoral support. And the Orange and paramilitary Loyalist forces continue to exert their own pressure. The DUP has undermined and diluted the initial Good Friday Agreement, with subsequent retreats such as the 2006 St. Andrews and 2015 Stormont Agreements. The Loyalist-initiated, and subsequently DUP-backed, 2012 Belfast Flag Riots orchestrated physical attacks on the liberal unionist Alliance Party. The latter’s marginalisation has meant that a British government, pledged to maintaining the Union, has had to continually appease the dominant reactionary unionists. Its difficulties in this regard were highlighted by its failure in 2013, even after bringing in US imperial assistance in the form of Richard Haas, to get the DUP to moderate its sectarian stance.

xxii. However, a key new element in Blair’s updating of ‘New Unionism’ was its extension from Northern Ireland to Scotland and Wales, with ‘Devolution-all-round’. The Irish government was also brought in, in a junior supporting capacity, to help create the optimum conditions throughout these islands for corporate profit maximisation. Neo-liberalism ruled the roost on both sides of the Celtic Sea. Whilst the intrinsically partitionist constitutional set-up in Northern Ireland prevented any liberal unionist road from developing there (and indeed provided a constitutional basis for a resurgence of reactionary unionism), the creation of Scottish and Welsh devolved assemblies were genuinely liberal constitutionalist measures.

xxiii. Liberal devolution prompted the Labour/Lib-Dem Holyrood and Labour/Plaid Cymru and Labour Cardiff Bay administrations to make use of these bodies to make some breaks with Westminster conservatism. No longer subject to the House of Lords, feudal land tenure was finally abolished by the Labour/Lib-Dem coalition in Scotland in 2002. It was the Labour/Plaid Cymru coalition (in the face of continuing opposition by some Welsh Labour and Tory conservative unionists), which pushed for the referendum to give Cardiff Bay the same powers as Holyrood in 2011. Cameron’s Conservative government provided official backing. This marked the highpoint of liberal unionism. It showed that the majority of the British ruling class, and its traditional first party of choice, the Conservatives, had been finally won round to ‘New Unionism’.

xxiv. But in today’s crisis-ridden world, nothing lasts long. It was the SNP’s proposed Scottish Independence referendum, and the failure of Labour to commit itself to further constitutional reform, which led to the demise of the British ruling majority’s commitment to ‘New Unionism’. The only reason that the Cameron government, backed by Miliband’s Labour opposition (Wendy Alexander’s “Bring it on!”), allowed the Scottish independence referendum to proceed in 2012, was because they thought it would be heavily defeated. Polling support at the time was between 28 and 33%. The SNP’s mounting political challenge could be seen off for a generation. Labour, under Miliband, backed by Gordon Brown, Alistair Darling, Jim Murphy, John McTernan, Blair McDougall and “branch office” manager, Johann Lamont, threw itself into the arms of Cameron’s Conservatives and formed (along with the Lib-Dems) Better Together or ‘Project Fear’.

xxv. The political essence of Better Together was a conservative unionist defence of the constitutional status quo, with a pretended liberal unionist gloss provided by Labour. This meant that Labour made all sorts of empty promises, which they were in no position to deliver. When the British ruling class took fright in the final weeks before the September 2014 referendum, following a narrow pro-independence majority poll, Gordon Brown was even wheeled out to make his notorious federal Britain promise.

xxvi. In IndyRef1, the combined political forces of conservative unionism, the mainstream media, especially the state’s BBC, constituted the main means to defeat Scottish independence. The ‘Yes’ campaign remained constitutional in its approach, although there was a much wider popular mobilisation than occurred around the 1979 Devolution referendum. The SNP government agreed to abide by Westminster rules in its campaign. These rules, of course, give a strong advantage to the UK state. Because of the official secrecy provisions, it will be many years before we know the full extent of behind-the-scenes state activities sanctioned under the Crown Powers. However, The Guardian revealed that UK state had plans to directly annex the Clyde nuclear bases in the event of a Scottish independence vote, creating a sort of ‘Guantanomac’ enclave. This was surely only one of the contingency plans drawn up under these powers.

xxvii. As soon as it became clear that Scottish independence had been defeated, Cameron ditched the liberal unionist mask, and donned that of the reactionary unionists, the better to defend the conservative unionist quo in the face of another challenge, this time to his Right within his own party and from UKIP . Thus he brought in English Votes for English Laws and the promise of a EU referendum. Although Cameron put on this reactionary mask to defeat UKIP and the Tory Right, it was his own victory over the SNP’s Scottish independence proposals, his Eurosceptic ‘exemptionist’ policies, and such anti-migrant activities, as May’s notorious ‘Go Home’ bus posters, that gave considerable impetus to UKIP and the Tory Right (several of whom were already in his Cabinet).

xxviii. During the IndyRef1 campaign Cameron had offered Scottish Labour the leading position in Better Together. After the 2015 general election, though, he was quite happy for Scottish Tory leader, Ruth Davidson, to launch the Tories’ own conservative unionist counter-offensive. Labour’s Right wing leader, Kezia Dugdale bowed to this at every turn, despite the spectacular failure of this strategy under former leader, Jim Murphy, when Labour were reduced from 46 MPs to 1! The first hint of the success of the Scottish Tories was their emergence as the second largest party at Holyrood in the 2016 election, replacing Labour. The SNP also lost its overall majority, but this represented a shift within the pro-independence vote, as the Greens gained seats, and provided support in Holyrood to back IndyRef2 sometime in the future.

xxix. UKIP and the Tory Right were successfully able to link EU membership and anti-migrant sentiment. In the 2014 Euro-elections, UKIP had won the majority of MEPs in England, came a close second in Wales, and even managed to win an MEP in Scotland. Previously opposed to devolution, UKIP’s work in Northern Ireland with the Loyalists showed it how to undermine devolutionary agreements from within. David McNarry, Assistant Grand Master of the Orange Order, had defected from the UUP and become UKIPs Stormont representative in 2012. In 2016, UKIP won 7 seats in the Welsh Assembly. Holyrood proved more resistant, and unlike England, Wales or Northern Ireland, UKIP failed to win any local councillors in Scotland. Nevertheless, UKIP became the only party in the UK to have political representation in all four constituent units.

xxx. Usually considered a ‘Little Englander’ party, UKIP was able to extend its support across the UK by appealing to all the state’s most reactionary features – the Crown, her majesty’s armed forces, the constitutionally privileged position of Protestants. They couple this to British chauvinist and racist hostility to migrants, and opposition to official support for minority languages, including Welsh and Irish and Scots Gaelic. UKIP’s state-imposed British ‘internationalism from above’ provided the template for the cross-UK reactionary unionist alliance, which has currently taken governmental form with the Tory DUP ‘coalition’.

xxxi. The dangers and possibilities presented by the reactionary Right’s spectacular Brexit victory in England and English-speaking Wales were quickly recognised by the British ruling class. They looked to their traditionally preferred political party, the Conservatives, to sort this out. After Cameron’s resignation, Theresa May with the compliance of the previously openly Brexit supporting Tory Right – Boris Johnson, Michael Gove, David Davis, and Liam Fox – donned UKIP’s coat and prepared for a ‘hard Brexit’, where “No deal is better than a bad deal’.

xxxii. However, the reactionary Right also wanted to use their Brexit victory to end the possible challenges provided by the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, and to ensure that Devolution could not offer any social democratic alternatives to full-on austerity. This could be done through a combination of cuts in the Westminster-allocated budgets to Holyrood, Cardiff Bay and Stormont, and by ensuring devolved powers are restricted to the devolution of responsibility for administering cuts.

xxxiii. Some on the Right also support their own form of devolution – to elected mayors, who are surrounded by business figures and like-minded officials. They act with almost total disregard to meeting the needs of their respective cities’ working class majorities, but concentrate instead upon attracting corporate business offices and retail centres, and the gentrification of residential areas. This soon leads to the corruption of officials and councillors, whose acquiescence is bought by various means, i.e. corporate ‘hospitality’ and sometimes direct below-the-counter bribes. This model took earlier root in England, after the failure of Labour’s John Prescott, in 2004, to deliver political devolution to the North East England (originally meant to be starter for all-round English regional devolution to complement Scotland, Wales and Stormont, in Spanish-style asymmetrical devolution combining subordinate nations and regions to dilute national democratic challenges). However, corporate corruption of local councils is found throughout the UK.

xxxiv. Both conservative and reactionary unionists felt that special attention had to be directed towards the threat that had so recently been made by the unexpectedly high Scottish independence vote. They also wanted to reverse the SNP’s steady march through the institutions of the UK state. This problem had been highlighted by the SNP’s spectacular winning of 56 out of Scotland’s 59 Westminster MPs in 2015. Ironically this was greatly assisted by Westminster’s first-past-the post system, which, to their credit, the SNP oppose.

xxxv. Focussing their attention on opposition to IndyRef2, a Tory and Labour alliance fought the April 2017 local council elections almost entirely on this issue, despite this not being within the remit of local councils. The Tories emerged as the second largest party in Scotland’s local councils, and also overtook and beat the SNP in several councils, particularly in the North East. The SNP did make an overall gain in council seats, but this was entirely at the expense of Labour, especially in Glasgow.

xxxvi. In Aberdeen, so blatant was the Labour group in its post-election Tory coalition deal to exclude the largest party – the SNP – that even Kezia Dugdale, faced with an up and coming Westminster election, had to suspend them. Other previously Labour controlled council groups quietly made behind-the-scenes deals with Tory councillors to exclude the SNP, e.g. in North Lanarkshire and West Lothian.