The following article by Allan Armstrong looks at the significance of the struggles around the issue of language in Ireland, Wales and England and how they provide a challenge to the UK state. An edited version of this was given as a talk to the Critical Labour Studies Colloqium, held in Aonach Mhacha, Armagh on 19.2.23.

THE LANGUAGE STRUGGLE AND THE CHALLENGE TO THE UK STATE

a) Introduction

On Monday December 5th, the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act was passed at Westminster.[1] On Thursday, December 8th, the consultation period for the SNP government’s proposed Gaelic and Scots Languages Bill[2] ended, clearing the way for legislation in the new year. The politics underlying these developments are convoluted but relate to the struggle over the future of the UK, not only in Northern Ireland and Scotland but in Wales and England too.

b) The Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act – Tory reactionary unionists forced to make liberal unionist concessions

The Tories’ backing at Westminster for the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act hardly reflects any commitment to either the Irish or the Ulster Scots (Ullans). Instead, facing pressure, they have fallen back on a longer, liberal unionist inspired tradition which gives recognition to minority languages in an attempt to uphold the Union in the face of potential political challenges – first Welsh (1993 and 1998 at Westminster)[3], then Gaelic (2005 at Holyrood with unionist support)[4] ) and now Irish and Ulster Scots (at Westminster, but opposed by the DUP, representing the Unionist/Loyalist bloc at Stormont).

Some hardcore Tory reactionary unionists still supported the DUP in their opposition to the Bill. But the otherwise reactionary unionist-dominated, Tory government sees this Act’s language concessions as a way to get the constitutional nationalists (Sinn Fein and SDLP) and the liberal unionists (Alliance Party of Northern Ireland) on board to restore the Northern Ireland Executive and Northern Irish Assembly (Stormont mark 2).

Unionists in Great Britain have long wanted to maintain Northern Ireland’s semi-detached constitutional status, under which its sectarian and fractious politics are kept well clear of Westminster and British media attention. If the DUP continues to boycott Stormont, then perhaps some other carefully selected laws will be imposed by Westminster, to undermine their continued intransigence. But the DUP will also be offered the carrot of further government backing to weaken the special position of the EU in Northern Ireland, following Boris Johnson’s insincere backing for the EU Protocol.

An Dream Dearg (ADD) is the principal organisation promoting the Irish language, and has mounted large demonstrations. The first of these, held on May 20th, 2017,[5] was organised in Belfast to protest against Sinn Fein’s prioritising the maintenance of its position in the Northern Ireland Executive over the promotion of the Irish language. And this year, on May 21st, ADD organised another large demonstration in Belfast[6] . ADD has active links to Northern Ireland’s communities of resistance, which had their origins in the Jaitacht[7] and the Shaws Road Gaeltacht in West Belfast,[8]during the ‘Troubles’. The UK government and Stormont, including the constitutional nationalists, all want to marginalise these. However, ADD, whilst quite understandably celebrating the passing of the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act, is less likely to fall in behind any liberal unionist or constitutional nationalist limitations.

c) The Welsh language connection, communities of resistance and EU backing for minority languages in these island

ADD also looks for inspiration to Cymdeithas yr Iath/Welsh Language Society (CyI/WLS)[9] with its social approach to language, seeing communities with their livelihoods as central to the maintenance of a living language. CyI/WLS has been the pacemaker for minority language development within these islands. Unlike all other Celtic languages, Welsh is no longer considered an endangered language. CyI/WLS’s long campaign of direct action, with many jailed, was very much based on local communities of resistance. CyI/WLS has been the principal force behind the significant achievements made for the Welsh language. Whilst Sinn Fein and Plaid Cymru are respectively supportive of the Irish and Welsh languages, both ADD or CyI/WLS remain grounded in the communities of resistance. They are prepared to challenge any backsliding by constitutional nationalists. And in looking to CyI/WLS, ADD has shown a wider internationalist approach to language not seen in Sinn Fein, SDLP. Plaid Cymru or the SNP.

Yet, despite the Welsh language’s official status in Wales within the UK, this position can still be reversed by future British governments under the UKs anti-democratic. sovereignty of the Crown-in-Westminster constitution. The reactionary unionist-dominated Brexit campaign brought this possibility into sharp relief. UKIP, the Brexit Party, many Tories and some Labour figures (and earlier, the maverick populist George Galloway) all declared their open hostility to the Welsh language. Jacob Rees-Mogg went as far as to call Welsh a “foreign language.” [10]

Whilst EU membership remained, its European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages provided the most effective support for the Welsh, Irish, Ullans and Gaelic languages. Therefore, it is not surprising that Welsh-speaking Wales stood out against English-speaking Wales in rejecting Brexit. But the reactionary unionist Brexiteers were unable to sustain their anti-Welsh language and often anti-Welsh Senedd offensive in the Senedd elections in 2021. The leader of the winning Labour Party in Wales, Mark Drakeford, is a liberal unionist and a Welsh language speaker. His new Labour Welsh government remains committed to the Welsh language and to increasing the powers of the Senedd.

However, there has also been growing support for Pawb Dan Un Faner Cymru/All Under One Banner (Cymru) with its commitment to Welsh independence. They are also backed by Undod,[11] the Welsh equivalent of the Radical Independence Campaign in Scotland. In the Welsh-speaking heartland of Gwynedd, the local council voted on 10th October, this year, by 46 to 4, to call for the abolition of the Prince of Wales.[12] Thus, there is a good possibility of further developments in the communities of resistance, which have long formed the backbone of the Welsh language.

In Northern Ireland, the original 1998 Good Friday Agreement (GFA) made provision for the Irish language by supporting Foras na Gailge (FnG)/Irish Institute (FnG/II), an all-Ireland body promoting the Irish language. The GFA also promoted Ulster Scots by supporting the Ulster Scots Agency/Boord o Ulster Scotch (USA/BoUS). Furthermore, the EU recognised Irish as an official language in the ‘South’. Most Unionists and Loyalists are opposed to any all-Ireland organisations. The late Lord Laird, with a pronounced, if at times eccentric, sectarian past and a history of expenses swindling and paid lobbying, was an early promoter of Ulster Scots to counter the Irish language and Irish Nationalism. He was a founder member of the USA/BoUS).[13] In an attempt to prevent the USA/BoUS being used for sectarian purposes, the EU also helped to create a regional Ulster Scots office in Raphoe, in east County Donegal in the Republic of Ireland. Historically many Scots had settled here.

But now that the UK has left the EU, this places the FnG/II in a more politically exposed position than CyI/WLS in Wales, strongly backed by the Welsh Senedd, or even Bòrd na Gàidhlig/Gaelic Board (BnG/GB) in Scotland (set up in 2005), backed by Holyrood. FnG/II’s official status now depends on Westminster, which has only ever conceded minority language rights after pressure from below.

d) Scotland and Ireland – Irish and Scots Gaelic, Ullans and Lallans

Now that the Scottish government has undertaken consultations over its proposed Gaelic and Scots Languages Bill, some attention has been focussed upon the Scots or Lallans language. Of all the long-standing languages spoken in these islands, Scots has received the least official recognition. This despite Scots derived dialects being widely spoken, particularly in working class and small farmer communities. In some ways the status of Scots is analogous to that of the Norwegian dialects whilst Norway was still ruled by the Swedish Crown.

There is no grassroots campaigning organisation equivalent to ADD or CyI/WLS for the Scots language (and that goes for Ulster Scots too). However there have been socially committed Scots language activists going back to Billy Kay and today they include for example Victoria McNulty, Len Pennie and Rab Wilson. And popularly supported writers and performing artists such as the late Edwin Morgan, Liz Lochhead, Elaine C. Smith, the Proclaimers and Alan Bissett make extensive use of Scots or Scots derived dialects, as does the internationally recognised author, James Kelman.

Some money has been set aside by Holyrood for the promotion of a Scots language dictionary and for the use Scots in the school curriculum. However, the main body promoting Lallans, the Scots Language Centre/Centre for the Scots Leid (SLC/CfrSL)[14] does not enjoy the official recognition given to the Welsh, Irish, Gaelic or even the Ullans promoting language bodies. But this could change if a new Gaelic and Scots Languages Act is passed.

However, despite the absence of the constitutionally entrenched sectarianism underpinning the Stormont mark 2 political order in Northern Ireland, there have been attempts in Scotland both to undermine the Gaelic and Lallans languages and to promote divisions between them. And such attempts to belittle minority language provision in Scotland have not been confined to Unionists as Stuart Campbell, of Wings over Scotland,[15] Scotland’s equivalent of England’s Katy Hopkins, has shown.

Sadly, in Ireland, some Republicans and Socialists replicate this division mongering. They display the mirror attitude towards Ullans that many Unionists and Loyalists have towards the Irish language – claiming it is only spoken by a few and promoted by Unionists and Loyalists for anti-Irish purposes. However, there are Ulster Scots speakers and supporters who do not see the promotion of this language in sectarian terms.

Indeed, Ullans has historically heavily influenced the speech of Catholics and Irish Nationalists in a swathe of Ulster from east Donegal through large parts of Counties Londonderry, Antrim and Down (north). Indeed, mirroring Linda Ervine’s commitment to the Irish language, there has been a Catholic presenter on the weekly Ulster Scots programme, A Kurst O’ Wurds[[16]. Some support for Ullans has more in common with those in Scotland and England, who champion rural and urban working class speech, and resent upper and middle class disparagement of their speech as ‘slang’ or ‘bad English’. Within Northern Ireland, Unionists elevated the Ulster landlords’ and business leaders’ spoken English and of course the Queen’s English. At times, they were prepared to patronise the ‘lower orders’ and their speech. Those Ulster Scots advocates who oppose this have already cooperated with Irish language speakers in organising joint events, especially for traditional music. The interpenetration of Irish and Ulster-Scots musical traditions is particularly strong.

Furthermore, going back to the political highpoint of Irish cross-community cooperation, uniting Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter, in the late 1790s, many of its United Irish advocates, particularly Ulster-Scots-speaking weavers and their poets, were to the forefront of this struggle. The mainly secular Presbyterian (Dissenter) Belfast leadership of the United Irishmen (and there were prominent women too, both Presbyterians and Catholics in their ranks) also promoted the Irish language and traditional Irish music. Their journal, the Northern Star, published an Irish language miscellany, Bolg an tSolair in 1795 and used the Irish slogan, Eireann go brach – ‘Ireland Forever’.[17] One of their members, Henry Joy, organised the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792.[18]

And the Scots poet, Robert Burns, who wrote much of his poetry in Lallans, was also sympathetic to the Gaelic language and music.[19] He had strong connections with Ulster, and some of its United Irish supporting weaver poets and with Henry Joy, who visited him in Dumfries.[20] Interest in Burns transcends a narrow cultural milieu and is international. Burns has recently been enjoying something of a revival in Belfast.

And more remarkable is the case of “Linda Ervine, one side of her family entrenched in a sectarian political agenda, most recently {in} the… UVF, another part of her family tradition… had a deep commitment to secular labour movement politics, through the Communist Party.”[21] She has become a prominent Irish language rights activist in East Belfast. She is closely involved with the Skainos Centre located in Lower Newtonards Road in East Belfast, a heartland of Loyalist sectarianism. The Skainos Centre is surrounded by many displays of Loyalist murals and paramilitary flags. This makes the existence and success of this non-sectarian, indeed anti-sectarian centre, also supported by the local Methodist Church of Ireland, significant. It houses the Turas Irish Language Programme.[22]

However, even Linda Ervine has been cautious over Ullans. She promoted a stand-alone Irish Language Act instead.[23] One reason for this may be seen in the first word of the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act. The use of ‘identity’ shows the Act is still framed within the terms of the bi-sectarian set-up of the Good Friday Agreement, with its constitutional backing for Unionist/Loyalist and Nationalist/Republican identities. Linda Ervine, with her Northern Irish Protestant background, does not want Irish to be equated to one identity or community. And even the UK state feels the need to court her. She was awarded an MBE in June 2022.

Attempts to bridge ethnic thinking which links language to one community or another are to be welcomed, both with regard to the Irish and Ullans languages, and their wider historical and contemporary connections. It would also represent a considerable socio-political advance if the Irish and Scots Gaelic, Ullans and Lallans languages, and their supporters in Ireland and Scotland, better appreciated these links. This means going beyond a dismissive plague on both your minority language camps, or seeing only one language as that of the ‘truly oppressed’. We need more meaningful solidarity to overcome the long-standing legacy of unionist division-mongering, sadly echoed by some cultural nationalists.

e)The languages of other minorities in these islands

There has been another divisive argument, promoted both by class biased unionists and cultural nationalists. This has been to dismiss the dialects and accents used by the working class and small farmers, including crofters. Schools have long been on the front line of such attempts at suppression. ‘Bad’ English, as well as Irish, Gaelic and Welsh, were often caned or belted out of students. But the use of derogatory verbal dismissals continued long after the abolition of physical punishment in schools and can still be found today. Some cultural nationalists argue, though, that any support for Scots dialects will undermine the re-emergence of their historically ‘pure’ or the emergence of the new synthetic Scots language, first promoted by Hugh MacDiarmid.

The Scottish Book Trust has argued powerfully against such thinking, particularly in its own field, that of education. “Celebrating the use of individual dialects can add richness to any classroom activities… By valuing each dialect equally, we can help our young people to respect the way other people in Scotland speak and learn about their own and other cultures and communities.”. [24] Nor is this seen in isolated Scottish terms. “It can help those with English as a second language to feel more valued, with all languages spoken in the class being considered together”.[25]

Such an approach challenges both the ethnic (cultural) basis of British nationalism (promoted by Gordon Brown and Michael Gove) and the increasing attempts by the reactionary unionist government to impose a Scottish-British provincialism. They are currently rolling back the limited democratic concessions made under Devolution and denying the right of national self-determination through the use of the anti-democratic Supreme Court.[26]

And, as well as opening up the discussion to those promoting regional dialects in England, such an approach also opens up the possibility of links with particular communities of resistance in England, e.g. Brixton in London, Handsworth in Birmingham and St. Pauls in Bristol. Once again, some Scottish nationalists, as opposed to Scottish internationalists, tend to dismiss any possible links with England, seeing only an undifferentiated chauvinism. But the Black-led communities of resistance in England have developed their own forms of the English language, demonstrated in the works of Linton Kwesi Johnson [27] and Benjamin Zephaniah.[28] Linton Kwesi Johnson wrote Inglan is a bitch.[29], rather letting unionist and imperialist Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland off the hook! In 2007 Benjamin Zephaniah rejected an OBE.[30] (Hamish Henderson, that great Scottish internationalist, and promoter of Scots dialects and Gaelic, author of the great internationalist anthem, Freedom Come All Ye, had also rejected an OBE in 1983.)[31]

The massive Black Lives Matter protests in England, especially in Bristol in 2020, and the post-Windrush and Grenfell Towers scandals, highlight the importance of people from Black migrant backgrounds. They have few illusions in the Union or Empire. Furthermore, their communities of resistance retain strong links with the Caribbean, which their former slave ancestors migrated from and where many of their relations still live. One former colonial British West Indian state after another – Bahamas, Barbados, Jamaica., Grenada, Antigua and Barbuda and St Kitts-Nevis – is questioning the Crown connection and pushing to be an independent Republic. This isn’t just seen as a political necessity but is also linked to the socio-economic demand for compensation for the horrific British imperial slaving legacy.

And this in turn takes back once more to that highpoint, in the late 1790s, of Irish cross-community cooperation, uniting Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter. There were divisions amongst the Irish Volunteers, with their liberal, Church of Ireland and Presbyterian members (and approved members of the Catholic Irish elite) and its more radical United Irish rank and file members committed to a more secular approach. The Irish Volunteer, Waddell Cunningham, promoted a slave trading company. In this he was opposed by the United Irish, Thomas McCabe, backed by William Drennan and Margaret McTier.[32] “James Napper Tandy condemned the French counter-revolutionary attack on Toussaint L’Overture”,[33] the leader of the massive slave revolt for full emancipation. “Another United Irishman, John Swiney, named one of his sons Toussaint.”[34]

Robert McVeigh and Bill Rolston, two figures from the politically engaged section of the Irish intelligentsia, have shown how these events “anticipated many of the later tensions between a self-interested Irish nationalism and more principled anti-colonial internationalism.”[35] Indeed, their arguments point to the contemporary relevance of such tensions in the campaigns for a united Ireland, under the current political conditions. On one side there is the possibility of Irish reunification, maybe within the British Commonwealth, but certainly under the City of London and its Irish banking subordinates, and accepting the existing neo-liberal economic order policed by NATO. On the other side there is the possibility of completing Ireland’s democratic revolution as a united Irish Republic, fought for by an ‘internationalism from below’ coalition, extending across these islands and beyond.

So far, no one has so clearly highlighted this distinction between these two traditions for national self-determination in Scotland, as shown by Robbie McVeigh and Bill Rolston in Ireland. This is because the Scottish-British component of the British ruling class was even more deeply involved in Black chattel slavery than the Anglo-Irish, the Ulster-Scots and later the Irish-British components of the British ruling class. The Scottish-British were to the forefront of imperialist endeavours. Union and Empire went hand-in-glove.

And this has contemporary resonance in Scotland. In the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests, Sir Thomas Devine OBE, Scotland’s leading historian and recent convert from Labour liberal unionism to constitutional Scottish nationalism, came to the defence of Henry Dundas, Viscount, later Lord Melville, and his statue in Edinburgh’s St. Andrews Square. Dundas was the Minister of War and the Colonies who helped delay the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade and heavily backed British imperial force to reinstate slavery in Saint Domingue (later Haiti), and upon the Jamaican Maroons, and the Garifuna of St. Vincent.[36] Devine tried to use his professional position as historian to curtail a debate initiated by another academic, Sir Geoffrey Palmer OBE. Palmer , with his Black Jamaican background, is not a professional historian, but a Professor of Life Sciences at Edinburgh’s Heriott-Watt University.[37] But in in the aftermath of Black Lives Matter, Devine was also challenged by the Black Canadian professional historian, Melanie Newton, based in Toronto,[38] (with its strong Orange imperial tradition, once called the Belfast of Canada) on the very historical grounds, which Devine tends to think he alone is fit to judge.

Devine is not a reactionary unionist, though, unlike Dundas and some of his other present-day apologists. Devine has written well about slavery’s key role in financing Scotland’s commercial and industrial development under the Union. Devine’s anti-slavery sentiments appear to be in the William Wilberforce liberal mould; something to be granted by the ruling class at a time that serves them best, and provided they are well compensated. Devine’s historical apologetics for Dundas in the past, indicate that, like the SNP leadership (and of course the British Labour branch office – Scottish Labour), he will not support any whole-hearted challenge from below today. Instead, he looks to the political leaders of the existing corporate capital dominated world to implement from above, at a time of their own choosing, the changes he would like to see. So don’t expect any support from Devine for a campaign of civil disobedience to challenge the UK government’s resort to the Supreme Court to deny any Scottish right of self-determination.

But others in the Scottish cultural field have begun to take up Black and other recent migrant authors and artists. This is shown in the Scottish Book Trust list, which includes for example, Lela Abouela, Safina Mazhar, Frank McChebe, Chitra Ramaswany, Tawona Sithole, Leela Soma, Surieh Tei and Sean Wai-Keung.[39] And, in Ireland, Robbie McVeigh and Bill Rolston show that, for example, Thin Lizzie’s Phil Lynott was “Guyanese-Irish, the singer and actress Samantha Mumba is Zambian-Irish, the footballer Paul McGrath is Nigerian-Irish, the actress Ruth Negga is Ethiopian Irish, – {and} the singer Loah Sally-Matu Garnett is Sierra Leonian-Irish.[40]

The British Empire and its successor Twenty Six Counties state in Ireland, were designed as a hierarchical political order, where all but the native colonial elites, e.g. nabobs and emirs, were allowed, at best, temporary residence to meet British war and economic needs, before they were meant to return to their original homelands. However, in defiance of these restrictions, many migrants became permanent residents, although always treated as second-class subjects. But their multicultural ‘internationalism from below’ traditions have become rooted in mixed personal relationships, communities and trade unions, and in new forms of cuisine, music and the English language.

Such developments were one of the main targets of the British reactionary unionist’s Brexit offensive. The UK state’s earlier state-policed ‘multiculturalism from above’, with its anti-racist laws and state-promoted quangos, was designed, from the late 1960s onwards, to draw in and divide the growing Black- and Asian- British resistance to the state’s deep-seated racism. This racism stemmed from the UK’s imperial legacy. But this settlement is now under attack from the Right (including Labour.) Yet, as with those earlier nabobs and emirs, it is possible today for the very rich and rich from ethnic minority backgrounds still to be fully accepted as British. To do this, they must support the existing socio-economic system in the UK, corporate capital’s global order, membership of NATO and all the wars needed to maintain this order. The current Tory government, led by Rishi Sunak, abounds in such people. Often their private school backgrounds also trained them to speak a different English to the majority sharing their ethnic backgrounds. The racist British Far Right may be appalled at this, but the British ruling class is more than prepared to augment its shrinking white numbers, if newcomers sign up fully to British chauvinism. And, showing that class far overrides ethnic background, Priti Patel and Suella Braverman have been to the forefront of attacks on asylum seekers and other migrants.

The Tory Brexiteers’ Nationality and Borders Bill is designed not to end migration (despite what the Far Right hoped) but to create a new hierarchy in the labour market. This would include permanent British residents, with greater employment rights, yet still within an ever more precarious workforce. Below them would be different grades of workers and students, allowed to take jobs or university courses for strictly allotted periods of time, when it is profitable for companies and higher education institutions to take them on. And there would be a third, super-exploitable, layer of non-documented workers, subjected to constant racist abuse and imprisonable and deportable at will.

And the rise of authoritarian national populism within the EU (and elsewhere in Europe), is likely to mean that many of the worst features of ‘Brexit Britain’ will appear in the EU member states too. Some of the preconditions for the promotion of a specifically ethnic Irish nationalism had already been put in place under the 2004 Irish Nationality and Citizenship Law. This has helped to provide the basis for the development of Hard and Far Right in Ireland. This has been shown by the 2018 Irish presidential candidate, Peter Casey, the independent TD Noel Grealish, Aontu, the Irish Freedom Party and Renua.

The conditions for the rise of this Hard and Far Right were also produced under the EU’s own imposed bureaucratic ‘internationalism from above’. This was policed by the EU’s existing state members on behalf of their various ruling classes. But in opposition to this, those people, who have been the product of the countervailing ‘multi-culturalism from below’, opposed Brexit. This was highlighted in London’s vote to Remain. It is this ‘multiculturalism from below’, politicised as a wider ‘internationalism from below’, that Socialists who opposed Brexit put to the forefront of their campaign.

f) Conclusion

But there is also a remaining obstacle to treating the issue of language and culture seriously and that comes from sections of the Left. They tend to think of capitalism in economistic terms, as primarily a system of exploitation. This leads them to concentrate on so-called ‘bread and butter’ issues, seeing political or constitutional matters as largely the concerns of the ‘chattering classes.’ But during periods of crisis, constitutional issues tend to come to the fore, and the ‘chattering classes’ are joined by more rooted classes, including the working class. This became very apparent during the 2012-14 Scottish independence campaign.

However, there is an even greater reluctance by many on the Left to address cultural matters seriously, including language. This, despite many individual Socialists’ strong commitments to say specific football teams and musical artists. But to address culture properly it is necessary to see alienation as the third prop for capitalism, after exploitation (the extraction of surplus value and unpaid labour for domestic work) and oppression (the denial of democratic rights). Furthermore, our answer to alienation is self-determination in its widest social sense, just as our answer to exploitation is emancipation and our answer to oppression is liberation.[41]

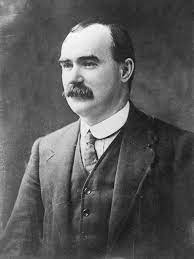

In relation to language, few have put it better than James Connolly. “It is well to remember that nations … which abandon their language in favour of that of an oppressor do so, not because of altruistic motives, or because of the love of the brotherhood of man, but from a slavish and cringing spirit. From a spirit which cannot exist side by side with the revolutionary idea.”

Such an understanding could help us to better appreciate one of the key forms that self-determination takes under capitalism – counter-cultural resistance and cultural celebration. The capitalist ruling class has developed formidable means to deal with our resistance. We have seen this in the decades-long capitalist counter-offensive since the last International Revolutionary Wave from 1968-75. Their success in this regard can lead to quite long periods of lowered economic and political struggle, and apparent worker acceptance of their rule. However, such is nature of the human creative mind that the reappearance of resistance often occurs first in the cultural arena. This resistance to alienation is harder to police, despite all ruling class efforts to do so.

Counter-cultural resistance and cultural celebration are key components of any attempts to assert greater national self-determination. Liberal unionism, constitutional and cultural nationalism cannot maintain the language diversity needed as part of a wider culturally diverse and environmentally sustainable world. This can best be done by uniting the exploited and oppressed on the basis of ‘internationalism from below’, to achieve self-determination in its widest social sense. For Socialists this should begin by promoting our unity in diversity across these islands. In the meantime, we can celebrate the passing of the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act and look forward to the passing of the Gaelic and Scots Languages Bill.

18.12.22

References

[1] https://belfastmedia.com/historic-day-as-irish-language-legislation-officially-becomes-law

[2] https://consult.gov.scot/education-reform/gaelic-and-scots-scottish-languages-bill/

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_language#Status

[4] https://www.abdn.ac.uk/sll/disciplines/gaelic/the-gaelic-language-323.php

[5] https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/thousands-join-irish-language-act-march-in-belfast-35736910.html

[6] https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/large-crowds-take-to-belfast-streets-in-support-of-irish-language-legislation-1.4885032

[7] https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Jailtacht

[9] https://www.dearg.ie/en/nuacht/2022-12-01-welsh-language-rights

[10] https://nation.cymru/news/jacob-rees-mogg-calls-welsh-a-foreign-language-and-compares-it-to-latin/

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/jul/11/lord-laird-obituary

[14] https://www.scotslanguage.com

[15] https://wingsoverscotland.com/the-lesser-of-two-stupids/

[16] Ian Malcolm, Towards Inclusion: Protestants and the Irish Language, p.218, footnote 68 (Blackstaff Press Belfast, 2009)

[17] Brendan Clifford and Pat Muldowney, Bolg an Tsolair, first printed by the Northern Star in 1795 (Athol Books, 1999, Belfast) Ian

p.218, footnote 68 (Blackstaff Press Belfast, 2009)

[18] John Magee, The Heritage of the Harp, pp. 8-13 (Linen Hall Library, 1992, Belfast)

[19] https://electricscotland.com/familytree/frank/burns_lives240.htm

[20] https://discoverulsterscots.com/sites/default/files/documents/2021-05/Belfast% 26%23039%3Bs%20Bonnie%20Burns%20%281%29.pdf.pdf

[21] Paul Stewart, Tommy McKearney, Gearoid O Machail, Patricia Campbell, and Brian Garvey, The State of Northern Ireland and the Democratic Deficit:Between Sectarianism and Neo-,Liberalism, p. 22 (Vagabond Voices, 2018, Glasgow)

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turas

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turas#Advocacy

[24] https://www.scottishbooktrust.com/uploads/store/mediaupload /2703/ file/Using%20Scots%20Language-%20FINAL.pdf – p.5

[26] https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2022/11/26/let-the-people-decide-3/

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linton_Kwesi_Johnson

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_Zephaniah

[29] https://genius.com/Linton-kwesi-johnson-inglan-is-a-bitch-lyrics

[30] http://republicancommunist.org/blog/2007/03/12/me-i-thought-obe-me-up-yours-i-thought/

[32] Robbie McVeigh and Bill Rolston, Anois ar theact an tSamhaidh – Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution, (AattrS/ICatUR) p. 339 (Beyond the Pale Books, 2021, Belfast)

[33] AattrS/ICatUR, p. 339 footnote 14

[34] ibid,

[35] AattrS/ICatUR , p. 339

[36] https://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/henry-dundas-naming-empire-and-genocide/

[38] https://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/henry-dundas-naming-empire-and-genocide/

[39] https://www.scottishbooktrust.com/writing-and-authors

[40] AattrS/ICatUR, p. 397

[41] http://republicancommunist.org/blog/2014/05/07/exploitation-oppression-and-alienation-emancipation-liberation-and-self-determination/ – Alienation

___________

also see:

The Irish Language Act is for everybody – Fergus O’Hare

Cultural capitulation and cultural resistance in Ireland – Socialist Democracy (Ireland)

Exploitation, oppression and alienation; emancipation, liberation and self-determination – Allan Armstrong, RCN – Alienation

https://www.oorvyce.scot/