This article by Ben Wray on the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune was first posted on bella caledonia.

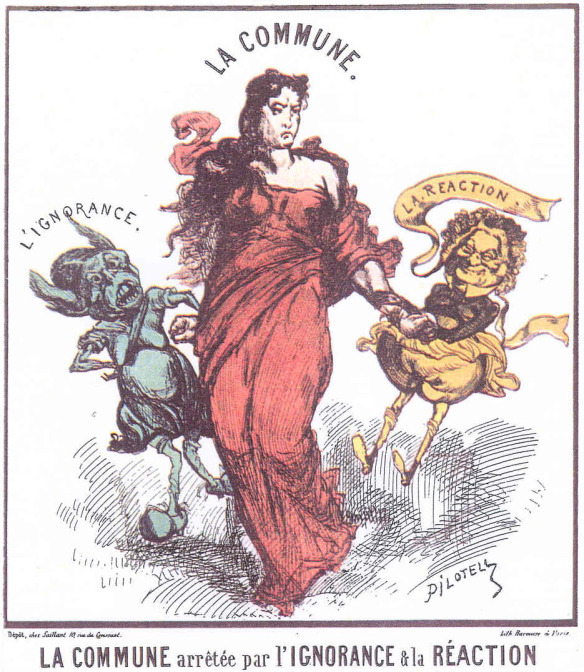

In the morning of 18 March 1871, a crowd of women in the Parisian working class district of Montmartre demonstrated. They were responding to the regular army of the French Government, fresh from defeat in a war with Prussia and now fearing civil war, who were about to seize the cannons of the National Guard (a voluntary force). The Parisian masses had paid for the cannons themselves through a public subscription, and were not about to give them up.

An army General ordered his troops to fire on the crowd three times, but they refused. Instead, the General and his officers were arrested by the National Guard, who were now openly fraternising with the demonstrators, and the cannons stayed in Montmartre. By the evening, barricades were up across Paris, and the French Government was fleeing the city for nearby Versailles. The next day, the red flag was raised above the Town Hall, the Hôtel-de-Ville, and an election was called. It was the beginning of the Paris Commune, one of the greatest experiments in democracy history has known.

The Commune only lasted 72 days before it was drowned in blood, in perhaps the most savage massacre of Europe’s 19th century. But those 72 days reverberated around the world, and has shaped the thinking of anyone seeking revolutionary change since. For the Commune was something unique; a municipal government run by and for the city’s poor and downtrodden working class. And this revolutionary administration had ideas, big ideas about how not just Paris, not just France, but how the world should be governed.

As one Communard, Arthur Arnould, wrote afterwords: “The Paris Commune was something MORE and something OTHER than an uprising. It was the advent of a principle, the affirmation of a politics. In a word, it was not only one more revolution, it was a new revolution, carrying in the folds of its flag a wholly original and characteristic program”.

In a speech in London commemorating the Paris Commune four years later, the Russian anarchist and Commune advocate Peter Kropotkin said: “The Commune did but little, but the little it did sufficed to throw out to the world a grand idea, and that idea was the working classes governing through the intermediary of a Commune—the idea that the state should rise from below and not emanate from above.”

150 years on, what ideas and strategies can we excavate from the Commune for the present day?

The Paris Commune and the arts: ‘Communal Luxury’

When looking at the Commune, one of the mistakes to make is to focus only on what officially was decreed in its short life-span, such as the free return of household goods and tools that had been pawned by desperate debtors, the suspension of rents, and price controls on food. All of that was important, but much more interesting is the processes that were at work at the base of the Commune, which was made up of volunteer committees who effectively ran different aspects of the city. These committees were led by men and women who had never previously been involved in public administration, and suddenly found themselves with collective power – and collective dreams.

Kristin Ross, in Communal Luxury – The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune (2016), invites us to pay attention to the committee of artists, which demanded “the free expression of art, released from all government supervision and all privilege.” State subsidies were considered to be a means of top-down control of artists, and in its place they sought “complete independence from the state” through agreeing to “share equally among themselves the ordinary tasks and requisitions commissioned by the Commune,” Ross writes. This revolutionary approach to organising artists’ labour is obviously relevant today, when artists struggle to make a living and have to compete with one another for subsidies, through state-funded institutions like Creative Scotland.

But the really big idea of the Commune’s artist committee was summed up in its manifesto: “We will work towards…the birth of communal luxury”. This manifesto was read aloud at a meeting of over 400 artists. One sculptor in attendance said: “The results of the manifesto’s propositions were enormous, not because they elevated the artistic level…but because they spread art everywhere.”

This is the idea of communal luxury: that rather than art being the preserve of elites, commodified as as a product to be sold to the highest bidder, it should be integrated into the fabric of all of our lives as an ever-present public good, accessible to all in its creation as well as its enjoyment. As Ross puts it: “At its most expansive level, the “communal luxury”, whose inauguration the committee worked to ensure, entails transforming the aesthetic coordinates of the entire community.”

There is no need to limit inspiration from the Commune’s artist committee to just the arts: the toppling of hierarchies through the de-commodified, collective association of labour can be applied across all sectors. And the turning of the concept of luxury on its head can also be thought of well beyond art: we need communal luxury in our relationship to nature, our transport policy, and much else besides. In an age where we must limit material excess to stay within ecologically sustainable boundaries, communal luxury is the only type of luxury we can afford.

Strategy and tactics of the Commune

There has not been a year since 1871 when the strategy and tactics of the Communards has not been scrutinised as part of wider debates about how to change the world. The Commune was an insurrection in the capital city, but while it had armed power it did not strip the French Government – which was allowed to regroup in nearby Versailles – of its arms when it had the chance. Neither did the Commune take full advantage of all the resources which were available to it within its territory, which included the Bank of France. Rather than seizing the bank and its gold, the Commune allowed the bankers to stay in control, a power they used primarily to help finance the French Government’s massacre of the Commune.

These were the great mistakes of the Commune, ones that Russian revolutionaries most notably would go on to learn from, but more interesting for us is the broader strategic dilemmas raised by what could be called revolutionary municipalism (some Communards afterwards described it as ‘anarchist communism’). Because there was a vision among Communards for how to spread the revolution beyond Paris.

The idea was for autonomous Communes to be established in cities across France and beyond, which would then be linked up in a decentralised and voluntary federation. It never came to pass due to the speed at which the Paris Commune, and some of the embryonic communes which did emerge in other French cities like Lyon, Marseille and St Etienne, were crushed, but nonetheless it is an interesting idea to think about in the modern context.

The obvious question which is raised by this city-orientated strategy is: what about the countryside? And indeed the inability to link the aims of the Commune to the pressing needs of the French peasantry was another major strategic weakness: peasants ended up being recruited into the French army to destroy the Commune. The political problem of a city v town/rural divide is fundamentally different today, but just as important.

We have seen in France with the ‘Yellow Vests’ movement how the geographies of revolt can shift – there is nothing pre-ordained about the city being in the vanguard. Post-industrial cities, including Paris, have been hollowed out by gentrification and over-tourism. The most recent census data shows that the share of Parisian residents defined as working class has declined to just 26 per cent, compared to 51 per cent nation-wide. Montmartre is now “an international tourist hub” and “prime real estate”. The city of Paris’ average age is over 50. Given these demographics, does the city still have the revolutionary potential of old?

“It is easier in towns than cities today, because people are more connected there,” Parisian activist Pierre Lalu tells Bella Caledonia.

Lalu is a member of ‘La 18 en Commun’, a municipalist project to take back the city’s 18th arrondissement. Like many municipal projects in Europe, Lalu’s was inspired by the successes of Barcelona en Comú and its mayor Ada Calou, who had built her reputation leading anti-eviction protests following the 2008 financial crash. La 18 en Commun did not win in the municipal elections last year, but is continuing a variety of projects based on municipalist principles: participatory budgeting, developing a local currency, a co-operative cycle scheme, and even seeking to create a digital app-game which would attempt to connect Parisians with one another.

Lalu, many of whom’s friends and family have left Paris because of the extortionate cost of living, says even the very idea of collective self-empowerment, which the Commune symbolises, “is a confused concept today”.

“People express this concept through ideas like the blockchain, or even through entrepreneurship as a means of empowerment, not necessarily in the old school municipalist way of taking collective, public power over the city.”

The case of Colau and Barcelona en Comú highlights the potential, as well as the limits, of municipal politics in the present era. Her administration has made important, if modest, achievements in rolling back neoliberalism in the city. But the problem of national politics has continually invaded the municipal-space, not least in the Catalan independence crisis since 2017, which Colau has struggled to adapt to, adopting a position between the independence movement and Spanish nationalism that has won few supporters.

At the level of the Paris administration, centre-left mayor Anna Hidalgo has sought to connect with the municipalist image of Calou, and has even achieved some results including introducing rent controls and restricting AirBNBs, but Lalu does not believe that there is a true municipal project emanating from the Hôtel de Ville today.

“It is a jewellery,” Lalu says. “They have no idea what municipalism is really.”

Winning ‘the Right to the City’, which Henri Lefebvre famously said was both “cry and demand”, is a battle in itself for the Parisian working class in 2021, never mind forging a revolutionary municipality.

Beyond Europe

However, take a step back from Europe’s ageing, gentrified cities and we can see that in much of the world, urbanisation is just taking off.

In China alone hundreds of millions of young workers have moved from rural to urban areas over the past 20 years, in the largest internal migration in history. The tipping point for a majority urban world was in 2008, with 68 per cent of people expected to be living in urban areas by 2050, and 85 per cent by 2100. New ‘mega-cities’ – population over 10 million – emerge every year, especially in Asia, and often have an average age about half that of Paris. Just like in Paris in the late 19th century, in the new mega-cities of the global south production and consumption – worker and citizen – intwine.

The Paris Commune may no longer be a model for Paris, but why not in Chengdu, Bogotá or Jakarta? 150 years on, the greatest Commune may still be to come.

Paris Commune Resources

To get a flavour of what the Paris Commune might have been like, I’d recommend Peter Watkins’ epic ‘La Commune’.

Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray’s first-hand account, ‘History of the Paris Commune of 1871’, is a great read. Eric Touissant’s essay on the Paris Commune, the banks and the debt is very interesting. As cited in the article, Kristin Ross’ “Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune” is available at Verso.

18th March 2021

This article was first posted at:- The Paris Commune’s revolutionary ideas – 150 years on

also see:- Emancipation & Liberation – Coverage Of What Is Communism?