Steve Freeman of the Republican Socialist Alliance and the Left Unity Party draws on the revolutionary democratic political tradition in England, linking the Levellers, the Chartists and the Suffragettes. He outlines its strengths compared with the social democratic and economist political tradition of Labour and most of the British Left sects. Steve argues that Socialists should be championing the revolutionary democratic tradition today.

THE COMMONWEALTH OF ENGLAND

“Westminster? It’s old, defunct, a waste of time. I hate the place” – Mhairi Black MP *

Westminster does not look or work any better from the inside or the outside. In May 1991 Tony Benn MP proposed fundamental reform. He introduced the Commonwealth of Britain Bill in the House of Commons, intended to make Britain a federal republic. The current Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn MP seconded the Bill. The Bill’s first hurdle on the parliamentary road to a republic was to get permission from the Queen to submit it to the Commons. Then there has to be majorities in the Commons, Lords and then finally with the royal assent the Bill becomes law.

In 1991 Benn told the speaker, “There is present in the chamber a Privy Councillor authorised to give consent”. It is little known that the Queen and Prince of Wales have the power to block proposed laws reaching the floor of the Commons. The Queen vetoed the 1999 Military Actions Against Iraq Bill which sought to transfer war powers from the Crown to parliament. Buckingham Palace explained the “long established convention” that the Queen is asked by parliament to provide consent to those bills which would affect crown interests. (Huffington Post 15 January 2013). Benn’s bill came into that category. The Queen graciously gave consent to a Bill that would not get beyond a first reading.

A second Bill was tabled in the Commons in 1996 to establish a democratic and secular Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Wales. It proposed to abolish the monarchy and the constitutional status of the Crown, abolish the Privy Council, disestablish the Church of England, and end British jurisdiction over Northern Ireland. It included proposals to reform the House of Lords and elect County Court judges and magistrates.

In his book Common Sense – A new constitution for Britain Benn explained his arguments [1]. A written constitution as the basic law of the country is central to the case for popular sovereignty. This would change the legal and institutional framework in which class politics and political struggle is conducted. His Bill proposed a referendum to seek the agreement of the people.

Tony Benn was ahead of his time in proposing a “Commonwealth of Britain”. But there were two major problems with his plan. First trying to introduce a republic through a loyal monarchist parliament is futile and more importantly the wrong approach. A republic will not come through a top-down approach spreading from parliament to the people. Of course making propaganda in parliament for radical democratic change has merit. But it is not a real or realistic process for democratic change. The people must win or take their sovereignty ‘from below’.

Second transforming a constitutional monarchy into the republic is no mean feat. There has to be a republican party committed to and capable of fighting for a republic. This is one of the lessons of history shown in the struggles of the Levellers, Jacobins, James Connolly and the Bolsheviks. Benn had no republican party, either in the country or in parliament. His battle in Westminster had no chance of progress. It hit a brick wall. He did not try to organise outside parliament.

Benn was not elected by the people of Chesterfield on a republican manifesto. He was elected on a Labour manifesto and acted as rebel against his own party, although consistent with his own democratic values and principles. He was committed to Labour, which was and remains committed to constitutional monarchy. It was a heroic and principled effort to raise the issue of radical constitutional change without real class forces behind it.

Democratic revolution

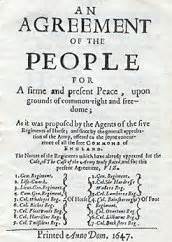

Tony Benn had a keen sense of history. The title of his Bill was an historic reference to the English democratic revolution. It is twenty six years since Benn presented his Bill and three hundred and sixty years since the House of Commons abolished the monarchy and the House of Lords. In January 1649, England became a Commonwealth, a republic which supported the common good or the well being of the people. The Levellers presented the House of Commons with a proposal for the Commonwealth to have a written constitution known as An Agreement of the People.

The Levellers were the republican party of the revolution. An Agreement of the People began life outside parliament. It originated through the 1647 Putney debates at St Mary’s Church within the ranks of the New Model Army. Power was already passing from the old regime through the victories won by a popular democratic revolution which culminated in 1649. This was not the end. The Commonwealth opened the door for a social revolution through the common ownership of the land.

In the Diggers occupation at St George’s Hill, for example, there was the potential extension of the republic into the economy of land and food production. Unfortunately by the middle of 1649 Cromwell’s counter revolution (within the revolution [2]) had taken over. The Leveller leaders were arrested. In May 1649 a mutiny by Leveller soldiers at Burford was suppressed. With the army firmly under Cromwell’s control the Diggers were driven from the land.

There have been many democratic revolutions. The fundamental difference from the ‘normal’ parliamentary road followed by Benn’s Bill is the mobilisation of people outside parliament and the growth of democratic mass movements asserting the sovereignty of the people. Of course such extra-parliamentary movements will be heard in parliament. But power is not in parliament. Its roots and strength are in the democratic organisation of the people in communities, trade unions and workplaces.

In this sense democratic revolution has more in common with the anti-poll tax movement and the anti-Iraq war movement or the 2014 political awakening around the ‘Yes ‘campaign in the Scottish referendum. In 1968-70 in Northern Ireland at the height of the struggle for civil rights, nationalists and republicans organised their own communities to repel the ‘B Specials’ and take control of “Free Derry”. Democratic revolution grows out of the self organisation of the people.

A social republic

Capitalism has transformed the world since the seventeenth century. It has created the modern working class whose productive power has transformed the world. Over the last two hundred years democratic revolutions have produced liberal republics, like America, with private ownership and free market capitalism and bureaucratic ‘socialist’ republics with welfare states, like the former USSR and Cuba. Democratic revolutions in the 21st century will have to learn from all these examples.

A social republic is a ‘mixed’ economy which makes public provision for the welfare of the people. It is not full state ownership, bureaucratic state capitalism, or socialism in one country. It does not mean abolishing capitalism or international socialism or world communism. However a social republic arising from a democratic revolution is a different kettle of fish. It is not simply or mainly about the extension of public ownership. A democratic revolution is the engine which drives the extension of democracy and workers’ control in both the public and private sectors.

A commonwealth is a fully democratic social republic. In the twenty first century, the lost ‘Commonwealth of England’ will be resurrected or reborn out of democratic revolution. It will not come from the Westminster parliament as Benn’s Bill proposed. It will be born outside parliament out of popular working class struggles. It will require the construction of new organisations – a republican party, a democratic movement and the self organisation of working people into democratic assemblies.

England crying out for democracy

Since 1991 there have been significant changes in the UK constitution, including devolution to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, the reform of the House of Lords, and the Human Rights Act. Devolution has left a vacuum in England with growing demands for an English Parliament and proportional representation. Democracy has been neglected by the traditional left and this has opened a space to be exploited by UKIP and the far right.

In 2014 the referendum in Scotland was a game changer. The impetus for democratic change throughout the UK came from the mobilisation of the Scottish people. Ending the Union between England and Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales is now the aim of all revolutionary democrats and prefigures the unity of progressive forces throughout the Kingdom. But the drive for this will come from Scotland and Ireland not from Tory England.

The UK may one day be replaced by a federal republic of England, Scotland and Wales as envisaged by Tony Benn. This will come after a peaceful and speedy divorce not before it. The Union state must be ended so that each nation can determine its democracy and freely choose whether to remarry on different terms or not. If Scotland wants to become a republic and England clings to its monarchy then the two nations will go their different ways.

Today the ‘crisis of democracy’ is not simply because more and more people do not believe that Westminster is listening to them or addressing their issues and problems. This is a ‘crisis’ because it is permanent, endlessly discussed but never resolved. The UK is stuck in a ground hog day, ever circulating around its permanent inability to move on. We are living in a long drawn out democratic paralysis. The old constitution is rotting and the stench is growing. Keeping this in place will pose an ever growing danger of authoritarian right wing reaction.

The 2016 EU referendum and the vote in England to leave the EU is a measure of the crisis of democracy. It highlights the desire for greater democracy, the danger of people being drawn to racism and chauvinism, the ability of right wing demagogy from the Tories and UKIP to exploit the crisis for reactionary ends. The idea of “taking back our democracy” was a powerful slogan and more dangerous because of popular myths about Great British ‘democracy’ and the ‘Mother of Parliaments’ rather than Mhairi Black’s “old, defunct, a waste of time” Westminster.

Chartism and Labour

Does England’s democratic revolution in the seventeenth century have any relevance today? Trotsky thought so. In his 1920s Writings on Britain he specifically references this period. He praises Cromwell as a revolutionary leader, “the Lion of the seventeenth century”. He contrasted Cromwell’s revolutionary determination with the liberal reformism of Ramsey McDonald and the Labour Party. Trotsky added another important historical reference to the Chartist Party in the 1840s.

An historical line from the Levellers can be traced through Tom Paine, the American and French democratic revolutions and on to Chartism. The demands of the People’s Charter were very moderate but the ruling class saw more democracy as dangerous and even revolutionary and dealt with Chartism by force. The Chartist party was the first mass working class party making democracy its political priority. They reasoned that without democratic political change the working class would have no influence on political power and this made social reform utopian.

In contrast Labour accepted the existing constitution of the Crown-in-Parliament as providing all necessary means of achieving social reform and socialism. All Labour needed was a parliamentary majority. Unlike Chartism, Labour did not seek to change the system of government but work within it. The Labour Party was first and foremost a parliamentary party and although members are active in trade unions and campaigns this is subordinate to winning elections. Labour is committed to principles of constitutional monarchy as Her Majesty’s Government or loyal opposition.

Chartism and Labour represent two distinct approaches to mass working class politics. Chartism was a mass working class political movement to force democratic constitutional change. It was an extra-parliamentary party fighting against anti-democratic political laws by mass action, strikes and demonstrations. Labour accepted the political system and worked through its institutions and laws, which have been designed to ensure that government policy operates within the narrow parameters of a conservative centre ground.

The party of democratic revolution

Between 1997 and 2007 the New Labour government supported Tory anti-union laws, privatisation, the Iraq war and the destruction of the welfare state. New Labour failed to regulate the banks and in 2008 the banking sector plunged into a major financial crisis. In 2010 New Labour lost the general election and Ed Miliband became leader. New Labour undermined the working class movement, saved the banks by nearly bankrupting the country and handed it to the Tory coalition.

Left Unity was set up in 2013 as a party to unite those on the left who wanted to fight New Labour. The new party was inspired by the “the Spirit of 45” the title of a Ken Loach film about the 1945-50 Labour government. At the founding conference the majority endorsed the idea of the party which defended the welfare state, opposed privatisation, opposed Tory anti-union laws, imperialist wars and NATO and supported public ownership. There were two minority positions – the call for a revolutionary communist party and for a party of working class democracy. The three historical reference markers were 1945 Labour government, 1917 Russian revolution and the 1649 English revolution.

There have been major and significant changes in UK politics, unimaginable in 2013. We have seen the 2014 Scottish referendum, the double election of Jeremy Corbyn and most significantly the 2016 vote to exit the EU. This demands a radical rethink. In 2015 Labour’s new leader reclaimed the “Spirit of 45”. Left Unity’s communists – Workers Power, CPGB and Socialist Resistance – left to join Labour. In 2016 the vote to leave the EU is the start of the biggest shakeup in class politics. The crisis of democracy can no longer be denied or ignored.

In 2017 Left Unity must prepare for new developments in the ‘crisis of democracy’. The working class movement needs a new kind of party more like the Chartist party than a pale imitation of Corbyn’s Labour. The desire for democratic change is widespread. As yet there is no mass party to represent this. There is no party of democratic revolution. There is no working class republican party campaigning for a social republic and workers control. Left Unity cannot simply create an alternative by wishing it but it must at least point the way.

Mhairi Black had not been born when Benn proposed his radical reforms in 1991. It is her generation that will have to carry forward the democratic revolution. They can take inspiration from Tony Benn’s Bill and the long historic struggle for democracy. Left Unity has to become the party that can link across the generations from Benn to Black by setting the clear goal for a ‘Commonwealth of England’ and new written constitution or An Agreement of the People in alliance with the people of Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Left Unity is well placed to stand in the traditions of the Levellers, Diggers, Chartists and Suffragettes. In Wigan, the Left Unity branch has shown the importance of 1649 in their annual Diggers Festival combining history and culture with contemporary politics. Celebrating the Wigan Diggers or the Burford Levellers has to be a central part of building a new party of the left – a party of democratic revolution.

13.3.17

- From The Guardian, 13.3.17

[1] Common Sense – Benn, Hood, Winstone ed 1993 Hutchinson

[2] My insert in brackets – AA

This was first posted at:- http://www.republicansocialists.org.uk

_______:

For Some Observations on The Commonwealth of England by Allan Armstrong see:

http://republicancommunist.org/blog/2017/04/07/the-commonwealth-of-england/

_______

also see:-