As part of our series of articles commemorating the centenary of 1916 Rising in Dublin, we are publishing the following article by Dave Temple of the Durham Miners Association, first published in their special journal for the Durham Miners Gala held on July 9th (see http://republicancommunist.org/blog/2016/08/03/david-hopper-and-the-durham-miners-gala/)

JAMES CONNOLLY, THE 1916 EASTER RISING AND THE DURHAM MINERS ASSOCIATION

100 YEARS ON

From its earliest years, the Durham Miners’ Association took a keen interest in political developments in Ireland. They were ardent supporters of the supporters of the Irish Land League-an organisation formed to fight for justice for peasants and tenant farmers against powerful Irish and British absentee landlords.

The issue of home rule for Ireland and Irish independence was debated from the Gala platform on many occasions by prominent Irish campaigners such as Irish nationalist leaders and former Fenians, Michael Davitt and John O’Connor Power, as well as intrepid British supporters of Irish home rule such as the militant atheist and passionate champion of women’s rights Charles Bradlaugh who spoke at the Gala on 11 occasions between 1874 and 1888.

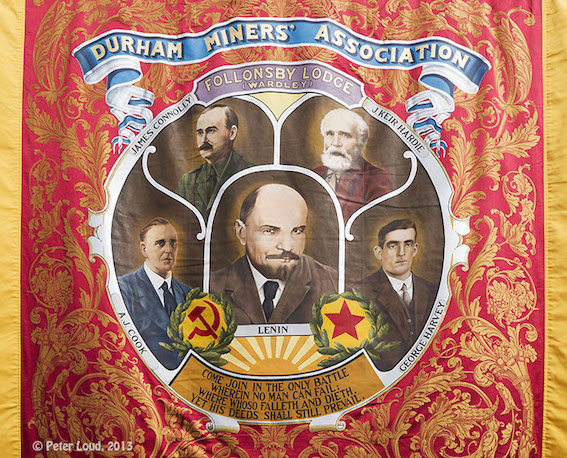

In this article, Dave Temple describes the Irish Rising of 1916 in the role of the Irish socialist leader, James Connolly, commemorated on the DMA Follonsby Lodge banner of 1928.

THE EASTER RISING, 1916

In the early hours of May 12, 1916, James Connolly, dying for a gangrenous bullet wound to his leg, was placed on a stretcher and, taken by ambulance from Dublin Castle to the city’s Kilmainham Jail. In the yard of the jail he was lifted from the stretcher and, unable to stand, was strapped to a chair – still in his pyjamas

The rifles of the twelve-strong firing squad had been loaded by a British army officer who placed a blank amongst the live cartridges – the “conscience round”.

A piece of white paper was then pinned to the left of Connolly’s chest to indicate the position of his heart. When the sergeant gave the order to fire, the intensity of the blast blew away the back of the chair on which he was seated.

So died a most remarkable man.

James Connolly was born on June 5, 1868 in the slums of Edinburgh, the son of impoverished Irish immigrant parents. He received only an elementary education up to the age of 11 after which he began to work at a printing house to help the family income.

After several changes of job, at the age of 14 he lied about his age and enlisted in the 1st Battalion of the King’s Liverpool regiment under a false name and first set foot on Irish soil when his regiment was posted to Cork in 1882.

One day, while leave in Dublin he met and fell in love with Lillie Reynolds a young Protestant woman they planned to marry sometime in 1888. However, when his regiment was posted to Aldershot, prior to deployment India, Connolly deserted and fled to Perth in Scotland. Lillie was to follow later.

From Perth, Connolly moved to Dundee where he met up with his older brother, John who had served in the British Indian Army but, unlike James, had been honourably discharged having served his full term.

It was John who introduced the 21-year-old James the ideas of socialism and, from that point onward, he never wavered in his belief that the only path of the economic and political emancipation of the working class lay in the destruction of capitalism and the establishment of socialism.

Connolly developed impressive leadership skills at an early age. His speaking style was precise and clinical and he wrote with uplifting eloquent prose. He finally married Lillie, the love of his life, in 1890 and struggled to make a living variously as an unskilled labourer, a cobbler and a socialist lecturer, none of which raised him out of the dire, hand to mouth, poverty that afflicted the majority of the working class of that time.

After an appeal for employment, printed in the socialist newspaper Justice, in 1896 he was offered the position of organiser of the Socialist Club in Dublin. In the same year, his third daughter was born and the growing family found lodgings in a single room in the heart of Dublin’s slums where as many as 20,000 families were housed in cramped and insanitary conditions.

LET US RISE

On May 28, 1886, under Connolly’s guidance, the Dublin Socialist club was disbanded and reformed as the Irish Republican Socialist Party with the now famous and inspiring slogan “The great appear great to us only because we are on our knees – let us rise!”

The ability to unite the desire of much of the Irish working class for independence from the British Empire with the establishment of a socialist Ireland set Connolly apart from his contemporaries, both in the developing socialist family and the more conservative nationalist movement dominated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

By 1898, Connolly had established a campaigning socialist newspaper – The Workers’ Republic. But life was desperately hard for the Connolly family in Dublin. Connolly and Lillie found it increasingly difficult to feed their growing family, dependent as they were on the meagre subscriptions of the small band of impoverished members. A fifth girl Moira was born in 1899 and their only son, Roddy, in 1901.

In 1902, to help raise money, Connolly embarked on a lecture tour of the USA organised by the Socialist Labour Party (SLP) of America led by the champion of revolutionary industrial trade unionism, Daniel De Leon.

CONNOLLY FAMILY IN CRISIS

By 1903, the economic situation of the Connolly family was in deep crisis. The movement proved unable to sustain the family and James’s efforts to gain work as an unskilled labourer were impeded by his declining health due to malnutrition. In July 1903, Connolly decided to take his family to the US where he could work and lecture for the SLP.

In America he engaged in a punishing programme of lectures and was periodically employed as an insurance agent, a sewing machine mechanic and labourer. He wrote prolifically and even had time to write poetry and a play.

In 1905, he attended the founding conference of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which became known as the “Wobblies” an all-encompassing union based on the principles of industrial syndicalism – “one big union” – and led by the legendary miners’ leader, William “Big Bill” Hayward.

In 1910, Connolly returned to Ireland and the first thing he did was to visit the leader of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU), James Larkin, who was, at the time, imprisoned in Mountjoy jail. Larkin and Connolly had formed a close relationship, by correspondence, in the last years the Connolly family had spent in the United States and, in 1911, Larkin made Connolly an ITGWU organiser in Belfast.

Connolly and Larkin were both unaware that over the next five years a remarkable coincidence of events will determine the courses of Irish and British history forever

The first event stemmed from the Parliamentary difficulties of the British Liberal party. In April 1912, Liberal Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, dependent upon the votes of the Irish Nationalist MPs, introduced a third Irish Home Rule Bill that so outraged the Protestant population of the northern counties of Ireland, in January 1913, Irish MP, Sir Edward Carson, formed the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). On September 28, 1913, 500,000 Ulstermen signed a covenant pledging to defy Home Rule and rise up against the British Crown.

They proceeded to arm themselves and, with the support and encouragement of the British Tory party and its leader, Andrew Bonar Law, set up a provisional government to rule Ulster in the event of the Home Rule Bill receiving Royal Assent.

The second event was a declaration of class war in Dublin. In the summer of 1913, William Martin Murphy, the leader of Dublin’s Employers’ Federation, challenged the growing influence of the ITGW by demanding all his employees give up union membership or be sacked.

400 employers followed Murphy’s lead and what followed was a brutal war of attrition against the working class of Dublin lasting six months. In the first few days of the lockout, hundreds of Dubliners were badly injured by police and two union men, James Nolan and James Byrne, so severely beaten that they died of their injuries.

The level of violence dished out by the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) so appalled Capt Jack White, a former British Army officer, that he approached Connolly with the idea of forming a workers’ defence force

On November 13, at the victory parade, to mark Larkin’s release from prison, Connolly announced the formation of what was to become the Irish Citizen Army (ICA).

He called for volunteers whom, he said, would be trained by a competent chief officer and added: “I will say nothing about arms at present – when we want them we know where we can find them”.

Just 12 days later, on November 25, leaders of the IRB with other Nationalists held a meeting in the Rotunda rooms in Dublin with the sole purpose of forming a nationalist militia in opposition to the UVF in the North. The meeting attracted several thousand men and women of whom about two thousand signed up to what was to be named the Irish volunteers (IV).

Members of the ICA were also present, armed with wooden sticks used for playing the Irish game of hurley. However, when they try to shut down Lawrence Kettle, whose family had locked out members of the ITGWU, they ejected from the meeting – an incident that highlighted an important class fault line in the social make-up of the two militias.

Towards the end of January 1914, relief aid from the British trade unions began to dry up and, despite repeated requests from both Larkin and Connolly for the British TUC to come to their aid by organising sympathy strikes, the British leaders remained obdurately opposed. With the ITGWU on the verge of bankruptcy, Larkin recommended a return to work on the best terms available at each workplace.

The union had not been definitively defeated… Connolly called it a draw. Many employers had broken ranks and given in as the businesses declined and, despite all Murphy’s machinations and the brutality of the DMP, the union, although weakened, had survived.

The lockout was over but the Home Rule crisis was deepening. By March, the British ruling class was split, the Liberal government contemplating coercing Ulster by force of arms, the Tories actively encouraging the UVF to stand firm and resist.

Some senior army officers were advocating that the officer class should resign their commissions and refuse to move against Ulster, while Bonar Law and the Tory party made assurances that all officers resigning their commissions would have them restored should the Tories win the next election.

Matters came to a head on March 20, 1914 when officers at the main army base at Curragh, County Kildare, many of them from prominent Anglo-Irish families, threatened to resign if the order was given to move against the northern Protestants. This stand, which became known as the Curragh mutiny, encouraged the Unionists but convinced the Nationalists that they would receive no support from the British Army and that salvation was to be found only in the hands of the Irish Volunteers and the Citizens Army.

DURHAM GALA, 1914

That year, James Larkin was chosen by the DMA lodges to speak at the Durham Miners’ Gala where he denounced the “lackadaisical and fossilised trade union leaders” to the great delight of the crowd but much to the disapproval of the Durham miners’ leaders.

As Larkin was speaking a yacht called Asgard was approaching the small port of Howth near Dublin. Aboard were 1500 single shot rifles, of 1870s vintage, bought in Germany and destined for the Irish Volunteers in the Irish Citizen Army.

Soon after the Gala, on August 4, 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. This was the third and most decisive event and the one destined to have the greatest impact on the history of Ireland. It was the big game-changer. Immediately, the threat of civil war in Ireland vanished as thousands of Irishmen from both the north and south of Ireland heeded the call of King and Country and flocked to the colours – but not all. James Connolly and the ICA saw Britain’s troubles as Ireland’s opportunity, a chance to strike a blow in the cause of Irish independence.

REVOLUTIONARY ARMY

After the Dublin lockout ended, the ICA did not disband and, although diminished in numbers, it was transformed from a defence force into a revolutionary army whose first principle was “the avowal that the ownership of Ireland, moral and material, is vested of right, in the people of Ireland”.

The dispute, though, had really sapped Larkin’s strength. Both physically and mentally exhausted, he was encouraged to go to America to recuperate and left Ireland for the USA in October 1914, leaving Connolly in charge of the union and the ICA.

Connolly was implacably opposed to the war which he saw as sacrificing the lives of the working class of Europe in the cause of capitalism. On the other hand, John Redmond, the nationalist MP who saw himself as a future leader of Ireland under Home Rule, supported the war and urged all able-bodied Irishmen to volunteer, effectively making himself a recruiting sergeant for the British army.

This split the IV, the vast majority of who joined with Redmond to form the Nationalist Volunteers, leaving the minority under the command of Irish nationalist and academic, Eoin MacNeill. The influence of the IRB within the volunteers now became decisive.

While members of the Nationalist Volunteers followed Redmond’s advice and departed for the carnage of the trenches in Flanders, the Irish Volunteers (IV) grew closer to the ICA and even started to cooperate, united in their fierce opposition to the war.

Both armies, however, were fighting an uphill struggle against the overwhelming wave of raucous “patriotism” that had engulfed the whole of Ireland.

Undeterred by the lack of support among the general population, Connolly campaigned fearlessly against the war and for Irish neutrality and hung a huge banner across the front of the ITGWU’s Dublin headquarters, Liberty Hall, declaring “We Serve Neither King Nor Kaiser”.

It took the authorities over two months before they had it removed, suggesting a little reluctance on their part to incite the Republicans. The ICA and the IV openly drilled and paraded through the streets of Dublin armed with rifles – incredible to our modern day security–conditioned minds.

Confident that the tide of opinion would eventually turn, leading figures of both armies met on September 9, 1914 to discuss striking a blow at the British Empire while it was distracted. Irish born former British diplomat turned Irish Republican, Sir Roger Casement was dispatched on a secret mission to Germany to acquire arms.

Between January 19 and 22 Connolly secretly met Joseph Plunkett, Patrick Pearse and Sean MacDiarmada and was sworn into the IRB, no doubt a union of convenience allowing Connolly to be co-opted onto the IRB military council and to be informed that they had set a date for the uprising. It was now guaranteed that the IV and the ICA would fight side-by-side in the coming conflict.

On Palm Sunday, April 16, 1916, Connolly dressed for the first time in military union uniform and stood while Molly O’Reilly, one of the many female soldiers of the ICA, hoisted the Irish republican flag – a gold harp on a green background – over Liberty Hall. Outside, a large group of onlookers cheered while members of the IV sporadically fired their revolvers into the air.

The time of the rising was set for the following Easter Sunday but almost immediately things started to go badly wrong. On Thursday, the Royal Navy intercepted the shipment of arms from Germany and the German skipper subsequently scuttled his ship, sending its cargo of vital weapons to the bottom of the Irish Sea.

The following day, Good Friday, Casement, landed from a German U-boat and within hours was in the custody of the Royal Irish Constabulary.

When the disastrous news reached Dublin, Eoin MacNeill lost his nerve and determined that the order to mobilise should be cancelled and sent messages to this effect all over Ireland.

Connolly, however, was unmoved and decided to go ahead with the plan. In this he was supported by the IRB Military Council but the day of the rising was postponed from Easter Sunday until the day after. On the morning of April 24, 1916, Easter Monday, Connolly and Patrick Pearse stood together in front of the General Post Office (GPO) on Sackville Street in the centre of Dublin. Before them a small, and somewhat bemused, crowd listened as Pearse solemnly read out the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

Already the combined forces of the ICA and the IV, now fused into one Republican Army were occupying prominent buildings within the Dublin’s centre and along the main routes into the city. Among them were aimed Eamonn de Valera commandant of the Third Battalion and Michael Collins, aide-de-camp to Joseph Plunkett.

The response of the British Empire was predictably swift, unsubtle and brutal. Crushing rebellion with overwhelming force was a well practised imperial tactic. But, in rushing soldiers and heavy artillery into the centre of Dublin, they were met by stiff resistance and took many casualties.

By Tuesday, evening martial law had been declared. Steadily, the big guns and machine-gun positions were established around the city centre and the patrol boat, Helga, sailed up the Liffey and trained her guns on Liberty Hall. A systematic pounding of the rebel positions in the city centre then set Dublin’s finest buildings ablaze and gradually reduced them to rubble, forcing the Republican army to evacuate the GPO, the symbolic heart of the rising.

By Saturday, there were an estimated 16,000 British soldiers in Dublin pitted against little over 1000 lightly armed Republican soldiers. Connolly was suffering from a second bullet wound that had shattered his ankle and was reduced to moving about on a bed mounted on wheels.

Realising that the rebels’ predicament was hopeless, on the afternoon of Saturday 29 April, a nurse, Elizabeth O’Farrell, stepped out into the street with a white flag to seek terms of surrender.

Unconditional surrender was signed by Connolly and Thomas MacDonagh and, by evening, the rising was over. Just under 500 people had been killed. The greater number, 260, were civilians, mostly killed during the bombardment of the city centre. Others were caught in crossfire.

British soldiers suffered 126 fatalities, the Royal Irish Constabulary 17 and the Dublin Metropolitan Police 3. Astonishingly, only 82 rebels perished in the conflict. But retribution was to be swift.

The army was dispatched to all buildings from which guns had been discharged with orders to shoot all occupants armed or not. It was this order to “take no prisoners” which was to gnaw away at the foundations of British rule in Ireland.

Although the rebels had considerable support within the working class ghettos of Dublin, many families whose breadwinners were fighting in France and Belgium and depended on the army for their paltry subsistence saw the Republican army in a different light. Many turned out to jeer the rebel soldiers as they were marched to Richmond Barracks to surrender their weapons.

However if the wanton shooting of unarmed civilians had begun to undermine Irish perceptions of the British Empire, the swift court martial and execution by firing squad of 15 leaders of the rising began a landslide of opposition to British rule.

In all 90 leaders were sentenced to death, but, Prime Minister Asquith, in one of his more sober moments, was persuaded of the rising tide of revulsion and called a halt to the executions. It was, however, already too late. The subsequent vicious sentences handed out and the internment of just under 2000 suspected rebels only rubbed salt into an open wound.

The fighters of the Easter Rising were quickly elevated to the status of “patriotic heroes” and in the first election after armistice in December 1918, Sinn Fein led by de Valera and campaigning for the establishment of an Irish Republic – by force if necessary – took 73 of the 105 Irish seats in the British Parliament.

This was to become the democratic justification for the Irish War of Independence of 1919 to 1921, leading to the establishment of the Free State and the ultimate partition of Ireland.

______

also see:-

THE EASTER RISING AND THE SOVIET UNION: AN UNTOLD CHAPTER IN IRELAND’S GREAT REBELLION