This article by Brendan McGeever was first posted on OpenDemocracyUK at:- https://www.opendemocracy.net/uk/brendan-mcgeever/easter-rising-and-soviet-union-untold-chapter-in-ireland-s-great-rebellion#.VvUvpKvURyY.twitter

THE EASTER RISING AND THE SOVIET UNION: AN UNTOLD CHAPTER IN IRELAND’S GREAT REBELLION

In a previously undocumented corner of history, research in old Soviet archives shows the extent of the USSR’s interest in Ireland’s Easter Rising.

It is early July, 1920. Roddy Connolly, teenage participant in the Easter Rising, is travelling without a passport in a cargo boat through the Norwegian fiords. The destination: Soviet Russia. As they edge towards the northern tips of the Kola Peninsula, the boat is blown off course by an incoming storm, pushing them some 250 miles towards the North Pole. After bouts of seasickness, they eventually dock in a besieged Murmansk, where Connolly begins a three-day rail journey across Civil War-torn Russia. Finally, he reaches revolutionary Petrograd, just in time for the opening of the Second World Congress of the Communist International. On arrival he is warmly greeted by Vladimir Lenin, who informs him that not only has he read his father’s book Labour and Irish History, but that he rates him “head and shoulders” above his contemporaries in the European socialist movement (1).

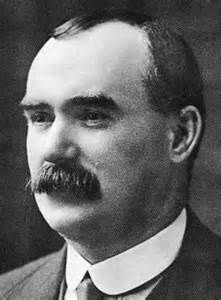

Roddy’s father was James Connolly, the Scottish-Irish revolutionary who led the Easter Rising of 1916. Though carried out by a relatively small number of poorly armed soldiers, the Rising had consequences all out of proportion to the military strength of its participants. It set in motion a chain of events that would eventually lead to the formation of an independent Irish Republic. As we approach the 100-year anniversary of this historic event, there is a chapter that remains untold: the story of how the Rising was remembered in the Soviet Union.

The Easter Rising caught the imagination of Bolshevik revolutionaries as soon as news of the events travelled across Europe. Leon Trotsky recalled the impact the Rising had on him in a letter to James Connolly’s daughter, Nora Connolly, in 1936: “The tragic fate of your courageous father met me in Paris during the war. I bear him faithfully in my remembrance”. Other Russian revolutionaries were similarly moved. In 1916 the Bolshevik Platon Kerzhentsev was living in New York in the same boarding house as the Irish poet and novelist Padraic Colum. When news of the Rising broke, Kerzhentsev offered financial assistance to Colum so that he could return to Ireland. Kerzhentsev’s connection with the Rising would be a lasting one: after the October Revolution of 1917 he established himself as a leading Soviet authority on Irish history, publishing various pamphlets and monographs that explained the Easter Rising for a Soviet readership.

Lenin and the Easter Rising

The most famous Soviet encounter with the Rising was Lenin’s. As Connolly’s army took the General Post Office in Dublin and raised the Irish tricolour, Lenin was in the throes of writing his theory of imperialism and national self-determination. Sensing that events in Ireland were confirming his new perspective, Lenin embraced the Rising as a decisive “blow against the power of English imperialism”. He was therefore aghast when fellow Bolsheviks like Karl Radek denounced the Rising as a “putsch” carried out by “petty-bourgeois” nationalist dreamers.

This dispute was far from trivial, for it went right to the heart of one of the key problems facing the Bolsheviks: how to develop a revolutionary strategy in an imperial context such as Russia, where national and class questions were fused. This became an acutely practical issue when the Bolsheviks came to power in October 1917, for they were suddenly faced with the difficult task of unifying the multinational Soviet state. Interestingly, the Easter Rising became a touchstone in these Party debates. Time and time again, the example of Ireland was raised in speeches by leading

Bolsheviks who promoted the principle of national self-determination. Lenin eventually won the day, and in 1922 a number of quasi-independent Soviet republics were established. The Easter Rising thus played its part in the formation of the Soviet Union.

Despite having its detractors, the Easter Rising enjoyed an overwhelmingly positive reception in the Soviet Union from the 1920s onwards. When the first Soviet accounts of the Rising were published, they invariably noted the “heroism” and “courage” of those who participated in it. During the early years of the Soviet state, the Rising also served as an important, symbolic resource of hope pointing to the possibilities of revolution in Europe.

The Easter Rising in an era of decolonization

Yet as it became clear that revolution had failed to materialize in the west, Bolshevik attention shifted towards the liberation movements of the Global South. In this changing context, post-War Soviet interpretations of the Easter Rising went through a subtle transformation. Now reframed as a specifically anti-colonial struggle akin to those taking place in Nigeria, Egypt and India, the Rising was repositioned within a Soviet lens whose gaze was directed at the decolonizing world.

Soviet interest in the Easter Rising had always been steady. Between 1918 and 1963 at least 25 specific works on the Rising were published in Soviet Russia. Things really took off in 1966, when the Rising’s 50th anniversary was celebrated at the 23rd Party Congress and various other meetings across Moscow. Two years later, the centennial of James Connolly’s birth was similarly marked in the Soviet capital, and in 1969, a Russian translation of Connolly’s writings was even published by the official Party publishing house. Amidst the new-found interest, Soviet biographies of Connolly were issued and doctoral dissertations were written in Moscow universities on the significance of the Easter Rising.

Translating the Easter Rising into Bolshevik Russian

Yet, despite all the enthusiasm, Soviet writers had long struggled to get to grips with the complexities of class, religion and nationality in the Irish context. When HG Wells arrived at the Kremlin in 1920, Party leader Grigorii Zinoviev quizzed him on the Easter Rising, asking “which do you consider are the proletarians, the Sinn Feiners or the Ulstermen?” According to Wells, Zinoviev could make neither head nor tale of the Irish situation.

One of the key problems facing those trying to render a ‘Soviet’ interpretation of the Easter Rising was its apparent religious character. When the Irish Proclamation was read outside the General Post Office in Dublin in Easter 1916, it began with the words “In the name of God…” Soviet writers tended to avoid quoting these overtly pious lines.

Settling on a suitably Soviet name for the ‘Easter Rising’ also posed great difficulties. The Russian term for ‘Easter’, especially if used in its adjectival form (paskhal’noe), risked framing the event as a distinctly religious event. Various alternatives were therefore adopted, including ‘The Irish Uprising’, ‘The Dublin Uprising’ and ‘Bloody Easter’. By 1966, some Soviet writers had simply taken to calling it the ‘Red Easter’. In this way, the Rising was translated into the language of the Russian Revolution: the Irish Citizen Army became the ‘Red Guards’, the British Army the ‘White Terror’

James Connolly: the ‘Irish Lenin’

Given Lenin’s high praise of James Connolly, it is not surprising that most Soviet treatments of the Easter Rising placed great emphasis on him. In the 1960s, when the Rising had become increasingly revered, even mythologized in the Bolshevik press, Soviet writers were routinely referring to Connolly as the “Irish Lenin”.

Yet earlier Soviet assessments had not been so favourable towards Connolly. In 1936 the aforementioned Kerzhentsev described Connolly as an “un-Marxist” radical who had failed to “overcome his syndicalist errors”. In the Second Edition of The Great Soviet Encyclopaedia, Connolly was similarly rebuked for having failed to distinguish between the “proletarian” and “petty bourgeois” elements of the Rising.

Not all treatments of Connolly were so overtly political. A 1966 article in the Soviet periodical Ogonek described Connolly as a “muscular, stocky man with a broad face and eyes that always shone”, almost as if he was one of the heroic Soviet monuments lining the streets of Moscow. Elsewhere, he was described as a working class guy who “liked a laugh, was a keen dancer and enjoyed a pint of beer in the evening”.

Legend has it that Lenin spoke English with an Irish cent (2). What is clear, however, is that the Bolsheviks read Irish history with a Soviet inflection.

(1) This account is based on Charlie McGuire’s vivid description of Connolly’s trip to Russia. See C. McGuire, Roddy Connolly and the Struggle for Socialism in Ireland, Cork: Cork University Press, 2008, pp. 20, 31-32.

25.3.16

About the author

Dr Brendan McGeever is a Lecturer in the Sociology of Racialisation and Antisemitism at Birkbeck, University of London.

I’m sure many will take issue with this but it takes a more critical view of Connolly

http://socialismoryourmoneyback.blogspot.com/2014/09/connollys-nationalism-equalled-betrayal.html#more