Ray Burnett, who lives in Benbecula, wrote the following article for Bella Caledonia on the continuing significance of the ‘Land Question’ in Scotland.

‘Divide and rule’. It’s the oldest game in town, so why on earth do we fall for it? Set up the polarities: Highlander/Lowlander, Gaidheal/Gall, local/incomer, crofter/environmentalist and let rancour commence. Scotland fractures, this great ‘Union’ of ours is thereby preserved and we will all live happily hereafter – ‘Better Together’ an’ a’ that.

These thoughts came to mind as I read my way through Domhnall Iain Domhnallach’s recent posting asking ‘Whose Land Is It Anyway?’ by way of response to an earlier spat over the promotion of Gaelic down in the South West and across Scotland generally. The array of issues Domhnall Iain touches on – the future of Scotland’s languages, our ‘wild lands’, the local governance of our island communities – are all important and worthy of further discussion. However, for brevity in this response I would like to focus on the core issue of: ceist an fhearainn, the ‘land question’.

The ‘land question’ in all its manifestations, I have for long felt, is an issue of particular and fundamental significance to the past, present and future of the left in Scotland. Firstly, it goes deep. It takes us to the heart of the matter as to what a struggle for ‘freedom’ in our contemporary world is ultimately all about, namely how we liberate humanity from the fetters of a capitalism order rooted in the practice of dispossession and the private appropriation of our common wealth and resources, sustained by the fetishised fictions of ‘market forces’. Secondly, it is an issue that has a specific resonance within Scotland because of the peculiarity of its place and importance in our social, cultural and political history. It takes us to the roots of our radical thought, the origins of our oppositional agencies and the legacy of inspiration and lessons to draw from an array of popular actions and struggle across a diversity of locations and particular cultural and social resonances. From this diversity and its achievements we learn some valuable lessons as to how success is achieved not by sowing division and internal discord but through the mobilising of a national-popular bloc that draws on, to borrow a phrase, a ‘national collective’ of shared cultural historical referents and memories, the agenda and the resources of an organically rooted Scottish left, as opposed to a left in Scotland.

A recent reading of David Harvey’s latest stimulating refresher, Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism, reinforces the validity of the first. A scan through some of the troubling divisions bubbling within the exchanges on this and related issues that filter through the contributions and comments to Bella underlines the dangers to the second. There is no better way for the toxic poison of manufactured division to enter the system of our body politic than through the open wounds of self-inflicted lacerations. By way of antidote let me attempt to cauterise the wound by offering a very different diagnosis of the Highland historical case notes.

Fuadach nan Gàidheal

The representation of the clearances as ‘the expulsion of the Gaels’ has a long pedigree. It can be traced to Donald MacLeod’s Gloomy Memories and its fuller explanatory subtitle — A faithful picture of the extirpation of the Celtic race from the Highlands of Scotland. MacLeod’ first hand accounts were widely circulated. But it was when they were subsequently incorporated into Alexander MacKenzie’s compendium The History of the Highland Clearances, that MacLeod’s accounts assumed their position as the standard narrative of the events they covered. Principal amongst these were ‘the enormities perpetrated in South Uist and the Island of Barra in the summer of 1851’, (the very events on the island estate of the Aberdeen-shire Colonel Gordon of Cluny that removed Domhnall Iain’s forebears from South Uist to Eriskay and many like them to the mainland and North America).

But there was a crucial elision in the account as subsequently re-presented by MacKenzie. When the forced emigrants from Barra went public with what had happened to them their testimony was scornfully repudiated and their character traduced by the public authorities on Barra. In a powerful passage on ‘The Exiled Barramen and their Calumniators’, MacLeod had scathingly denounced this local resident network of the absentee landlord’s authority and power as ‘vicious dogs’ to be classed alongside ‘the Devil and his angels’ and deserving of the same eternal fate. Yet, as he must have been aware, ‘the oppressors of the poor’ of the poor he was so intent on exposing, were all themselves island Gaels, each firmly embedded in Gaelic society and culture, each with their own deep kinship lineages and sense of ‘dualchas’. Precisely the same applied to those responsible for the parallel events on South Uist. But when MacKenzie came to re-present Macleod’s account in the form it has been commonly received ever since, he omitted this critical passage of criticism and exposé of the complicity of fellow Gaels. This better facilitated the presentation of these forced emigrations of 1851 as moments in a deeper, wider process: the systematic ‘ethnic cleansing’ of an indigenous culture and people by other non-Gael external forces fuelled by institutionalised racism.

That there was an ethnic and racist element involved is not in doubt. But once the ethnic and cultural dimension is introduced the real tragedy is not the in the compulsion of the clearances but in the complicity. It was an awareness of this that led Neil Gunn, when asked later why he had written only one novel on the Clearances (Butcher’s Broom), to give the painful reply, ‘Because of the shame of the thing.’ And pressed as to why he personally felt so ashamed, so long after the event, he put it in the starkest possible terms: ‘Because our own people did it’.

Nowhere was ‘the shame of the thing’ more manifest than on the islands of Benbecula, South Uist, Eriskay, Barra and the Barra Isles. The proprietor, Colonel Gordon of Cluny, was indeed, a non-Gael. But the beneficiaries of the wholesale evictions carried out on his island estate, the tacksmen who took up the tenancy of the newly created grazing farms were all Gaels. All those who continued to hold the tenancy of these farms under his successors were Gaels. And all those in authority in the islands who subsequently praised the memory of the late landlord as an outstanding benefactor of his tenants and all who implemented the pursuit of policies based on the continuing promotion of emigration, the curtailment of crofting and the denial of the restoration of land for resettlement were also Gaels.

Màiri Mhór nan Oran and the ‘Crofters’ War’

A similar pattern of complicity prevailed elsewhere throughout the Gaidhealtachd, not least on the Skye, the island that emerged as the focal point in the 1880s of an emergent resistance. Domhnall Iain rightly flags up the role of Màiri Mhór nan Oran as the embodied voice of the resurgent people but in doing so he makes a virtue out of what was, in fact, her principal weakness. No one championed the poetry and song of ‘Big Mary of the Songs’ more passionately than Sorley MacLean who felt strongly that ‘her limits have been exaggerated and her merits depreciated.’ Yet it was also MacLean who drew attention to the fact that ‘inconsistencies abound’ in the contradictory array of those she praised and those she condemned. He was unambiguous in his criticisms of her misplaced allocation of blame, noting that ‘she attacked the English for their doings in Skye, although it was very plain that not one Clearance had been made in Skye by anyone who had not a name as Gaelic as her own.’

MacLean shared Màiri Mhór’s deep sense of attachment to the places, the people and the cultural landscape of Skye and his own native island of Raasay. He was, however, all too aware that the systematic clearances of Raasay’s townships, the memory of which will endure forever in his timeless lines on ‘Hallaig’ and ‘Screapadal’, were also a terrible consequence of the Gaelic complicity that Màiri Mhór found so difficult to acknowledge. And, as his early writings make clear he was conscious of a capacity for ‘intellectual shufflings’ amongst the bards of Gaeldom as they sought to avoid the unavoidable as to the extent of collusion within the Gaidhealtachd as to what happened to the people, their land and their culture.

It is a measure of MacLean’s own intellectual courage and integrity as much as the acumen of his observations that even when introducing a seminal paper on the subject to a body (the Gaelic Society of Inverness) whose roots were firmly in the very ambivalency that he was addressing, MacLean did not present ceist an fhearainn, ‘the land question’, in racial or ethnic terms but in the unambiguous language of capital and class:

‘The Highland Clearances constitute one of the saddest tragedies that has ever come on a people, and one of the most astounding of all the successes of landlord capitalism in Western Europe, such a triumph over workers and peasants in a country as has rarely been achieved with such ease, cruelty and cynicism.’

What is more, he went on to argue, the principal causes of the emergent note of ‘courage and hope’ in the ‘resurgent spirit’ of the 1880s, were to be found external to Gaeldom, not least in the emergence of working class radicalism in Scotland’s Lowland cities and the active agitation driving forward the struggle for land in Ireland.

Vatersay and the post-WWI Land Raids

As Domhnall Iain notes the resistance gained the Napier Commission and the Crofters’ Act 1886. It did not, however, win back the land. This process did not begin until a sequence of land raiding began on Vatersay in 1906. Stalled in 1914 by the hiatus of the Great War, over 1918-1923 it was galvanised by the latter into a proliferation of direct action land seizures across the Highlands and Islands in the post-war context of failed promises and wider social upheavals. As with the earlier 1880s, for Gaeldom this was also a period marked by a combination of complicity within and commonality beyond. The lines of opposition and alliance were determined not by the identity of race, ethnie or language but by the interests of class. Although the period of extensive land seizures and consequential legal proceedings was also the era in which there was a resurgence of promotion of Gaelic language and culture by a growing body of Gaelic cultural enthusiasts and societies, the noticeable absence of public expressions of support for the imprisoned raiders, their families and communities by leading Gaelic cultural figures and agencies is striking.

Those who were aware of a common cause and who expressed it accordingly were the working men and women of Lowland Scotland, from the dispossessed crofters and farm servants of the rural hinterland, the women campaigners against landlordism and rack-renting in the slum tenements of the cities and the miners who challenged land and mine owners over ‘ownership’ and control of the resources of the land. When, in 1906, the protracted and ultimately successful campaign to reclaim the island of Vatersay began, it was the columns of Tom Johnston’s Forward and the meetings and resolutions of an array of Trades Councils across Lowland Scotland that rallied support behind the Vatersay raiders. Significantly, when all Scotland, not least the crofting communities of the Highland was carried along in the jingoistic imperial patriotism of the Great War, it was over the iniquities and power of landlordism that Johnstone’s Forward and the wider Left in Scotland were able to sustain a campaign to expose in whose class interests the war was ultimately being fought. They did so by focussing on landlordism – ‘The Pure Milk of Prussianism’ as it was described in relation to the Glasgow women’s housing campaign. In this promotion of a shared resistance to the landlords of the Highlands, the profiteering mine-owners and big farms of the rural Lowlands and the rack-renting landlords of the cities, urban and rural working class families, Gael and non-Gael, were thereby drawn together in a national-popular struggle against ‘The Huns at Home’.

Nor – and this is the crucial point – was this notion of a common cause something that was somehow foisted on the Gaelic communities of the Highlands from the outside. Nowhere demonstrates this better than out here in the Uists and Barra, the very islands on which Domhnall Iain constructs so much of his argument for Gael/Gall antipathy. The history of the struggle for land in these islands over this period shows quite clearly that from the outset the raiders and their communities had a deep sense of solidarity, a clear awareness of commonality and a strong feeling of empathy with the rural and urban struggles of the people of Scotland from the Barra Isles to Buchan, from Shetland to the Borders. When the Vatersay raiders attacked individual Lords who had made pronouncements on the land issue, they were put down in no uncertain terms not just for their ignorance as to the reality of life in the crofting townships as opposed to the deer forest and grouse moors, but also for their equal lack of awareness of hardship and adversity elsewhere in Scotland, not least in the congested squalor of the urban tenements.

It was a consciousness of class that also drew on the solidarity of nation, a sense of the national-popular that most vividly expressed itself in relation to the governance of Scotland from Westminster. When, in context of the constitutional ‘Peers versus the People’ crisis, the Lords also blocked a Scottish Land Bill designed to facilitate a limited degree of land settlement through a modest measure of land reform, they were immediately denounced by the Vatersay raiders in scathing and angry terms. The response was not couched in terms of the localised grievance of a small outlying community, nor in the wider terms of the ‘dispossessed Gaels’ of the Gaidhealtachd, bit in the battle front numbers of Lords of Westminster versus the Scottish nation. ‘There are four hundred of you’, declared the Vatersay raiders, but, ‘there are four million of us’.

Class and nation also drew on wider circles of consciousness. After 1917 the seizing of the land by direct action was widely and disapprovingly reported in the Scottish press as ‘Bolshevik tactics in the Highlands’, an ‘alien’ imputation that did not distress the raiders and their support. In 1919 the Greenock branch of the re-formed Highland Land League cheerfully concluded its meeting with two Gaelic songs and the choir singing the International. And as an old North Uist raider told me of the itinerant visitor he remembered who acted as their contact with their supporters in Glasgow and the mainland: ‘Oh, he was a great friend of the crofters. He must have been a Bolshe-ayvik, or something.’

When a ‘national committee’ for Scotland was formed, Angus Macdonald of the HLL and Joe Duncan of the farm servants union joined leading Clydesiders, including the great John MacLean, to issue a manifesto declaring that Scottish workers were being held back by the sluggishness of the less-progressive English labour movement. They must go it alone for socialism. Nowhere is this promotion of a radical ‘national collective’ agenda more evident than in the aims of the reconstituted Highland Land League itself. Its stated objects included, ‘the return to the people, for their use and enjoyment, of the land taken from them and now held in large areas by nobles and other landholders in the Highlands of Scotland’. This, however, was prefaced by the first declared aim of the HLL: ‘1. The objects of the League shall be to secure Autonomy for Scotland’, the emphasis being in the original. The means of achieving this, the discussed and adopted land policy declared, would be through the State assuming public ownership and possession of all the land, lochs and rivers of Scotland.

The radical Gaels of the HLL, however, had their own reactionary counterpart. While the HLL and their non-Gael Lowland allies came together in a shared opposition to landlordism on a national-popular agenda of ‘expropriating the expropriators’, the Gaelic petit-bourgeois of the Highlands, the dominant social force in Inverness, the Highland capital, and across the small town network of the Highland counties, was strident in its defence of property, privilege and the prevailing order. The Highland hegemony of landlordism was built not on coercion but on complicity. In the Uists and Barra it was John MacDonald, Lady Gordon Cathcart’s resident factor, a Gael who despised crofting as much as Catholicism, who dutifully warned her ladyship how the crofters and Gaels of the islands were aligning themselves with fellow malcontents in the Lowlands and beyond. The young men returning from the Army, he reported, ‘appear to be polluted with revolutionary ideas’, an influence, they both agreed, that could be easily traced to Glasgow. While ‘this unfortunate state of affairs’ was prevalent throughout the Hebrides, on the predominantly Catholic islands of Benbecula, South Uist and Barra, there was an additional subversive element. Deeply anxious for the threat it posed to estate authority, landlordism and the established order, Macdonald loyally informed her ladyship that ‘over and above Bolshevist ideas’, there was ‘clear evidence that Sinn Fein ideas are rampant… and one hears on every hand threats being made to establish a similar state of affairs in the islands as we have in Ireland today.’

‘Whose land is it anyway?….’

Domhnall Iain asks the Left to ‘pay attention’ to the Highlands and Islands in the move to and beyond independence and cites fellow Gaelic activist, Angus MacLeod who argues that to gain ‘an understanding of the experience of those marginalised by economic exploitation, then a genuine engagement with an exploited culture close to home, is … a good place to start.’ This basic proposition that the Left needs to understand how social and economic exploitation within capitalism is lubricated and facilitated through cultural hegemony and the concomitant processes of subalternity I readily concur.

However, in relation to whichever of our many Scotlands we are addressing, an appreciation of how this subtle process of induced inferiorisation and self colonialism works will never be gained by an uncritical reassertion of the essentialist binaries of the past. Engagement with the plurality of our exploited cultures – and recognizing this plurality is crucial – requires not only a critical revisiting of history but an acknowledgement and understanding of the extent to which collaboration and complicity were a core element in the exploitative process just as solidarities and a sense of common cause across these binaries was a key dimension to successful opposition and resistance. In drawing on the essentialist discourse of the past to remind a present generation of past hardships, struggles and achievements it is imperative to retain a critical awareness of the context in which these polarities were constructed.

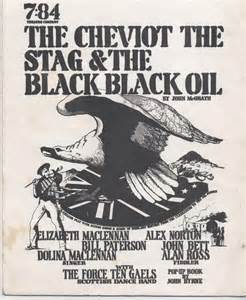

In charting the long march of campaigning on the land question in the Highlands since the 1880s, Domhnall Iain flags up the input in the early 1970s of 7:84 (Scotland) Theatre Company and the West Highland Free Press. Sadly, 7:84 is no longer with us and the epithet ‘radical’ has long ceased to be meaningful in relation to the pavlovian labourist unionism of the WHFP (aka The Unfree Press). However the engagement with the land question in that brief window of ’73-’75 was significant, not least, of course, in the tour and subsequent tv transmission of 7:84’s ‘The Cheviot’.

All the more ironic that 40 years on Domhnall Iain’s chooses to conclude his own idiosyncratic account of campaigning on the land question in the Highlands with the same lines from Màiri Mhór’s Eilean a’ Cheo with which The Cheviot ended, the high optimism as to the future of Skye when the wheel will turn, the resources of the earth will be available to the people and the ‘Sasunnaich’ will be driven from the Green Isle of the Mist. In drawing on ‘the big brave heart’ of Màiri Mhór na Oran, The Cheviot sought to end on a note of high optimism that went beyond localism and circumscribed grievances (as the next generation of land raiders did) through the building of common cause national-popular alliances against the formidable power of global capitalism. Both here and related writings there was a careful utilisation of powerful essentialist poetry and song for a national liberating political purpose, a deployment that has been subsequently described as strategic essentialism.

It is sad that Domhnall Iain seeks to use the same songs not to take us forward or to promote unity but in the service of a misguided tirade against illusory enemies and a divisive polarisation as to who ‘belongs’ and who does not.

Those who seek to defend and promote both our Scots and our Gaelic languages and cultures, or to protect the biodiversity and vulnerable environment of the ‘wild lands’ of our ‘wee bit hill and glen’ against inappropriate developments and exploitation by multinationals, or to defend the people of our small towns and big cities against the loss of common lands to speculative property development and the communities of our inner cities against gentrification and anti-social landlordism are allies, not enemies. Discussion and debate over emphasis, or balance is positive and healthy. Denigration and division over ethnie or language over ‘native’ or ‘foreigner’ is debilitating and damaging, particularly at this critical juncture in the campaign. Perhaps the best way forward is to step back from further acrimony and re-unite around the answer to the question ‘whose land is it anyway?’ given in

This land is your land, this land is my land ……..

This land was made for you and me.

With Pete Seeger’s pertinent additional verses added on for good measure, of course.

This article was first posted at:- This land is your land, this land is my land

also see:-

History and Resistance: The Rise of Latin America’s Indigenous Movements

Three Reviews Of Allan Armstrong’s ‘From Davitt To Connolly’ (with replies)

A new review of ‘From Davitt to Connolly’ by Tara O’Sullivan

For a rural south perspective on the ‘Land Question’ see http://radicalindydg.wordpress.com/2013/09/14/the-duke-the-mines-and-the-black-black-coal/

Thanks for this very useful link Alistair. In the follow-up to the work I did on the Covenanters, (see http://republicancommunist.org/blog/2003/08/03/beyond-broadswords-and-bayonets-2/) I found your own work on the Lowland Clearances very informative.

Just whoe land? Editorial of the Socialist Standard http://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/socialist-standard/2010s/2014/no-1321-september-2014/editorial-it-better-be-exploited-one%E2%80%99s-fellow-c

‘If they speak consciously and openly to the working class, then they summarise their philanthropy in the following words: It is better to be exploited by one’s fellow-countrymen than by foreigners.’ (Marx, 1848)

A separate parliament in Scotland would be a capitalist parliament. It would not provide Scottish workers with any greater control over their own lives. Scotland would remain an integral part of international capitalism. An Edinburgh sovereign parliament will leave the workers in exactly the same position as before.

Scottish nationalism is the reaction of one section of the Scottish capitalist class to what they perceive as the declining fortunes of British capitalism and their ‘unequal’ treatment within it. They seek to keep the taxes on North Sea oil revenues and create a corporate tax structure more suited to their own needs. The SNP advocate industrial harmony and an end to class conflict. They entice Scottish workers with offers of a reformist programme and wild promises of more money and a better life. But no natural resources will be put to a sensible or beneficial use until the working class itself has gained control over the use of these valuable and non-renewable resources.

The question of independence threatens relations between English/Welsh and Scottish workers. Scottish workers are asked to place their trust in the local employing class rather than in unity with other workers. United working-class action cannot be easily achieved by insisting that there are supposed national differences in consciousness that distinguish Scottish workers from, say, their English brothers and sisters. And certainly it is not aided by combining with particular Scottish bosses, which lead Scots working people to identify with Scottish businessmen and landowners on the basis of shared ‘nationality’.

Working class unity enables us to combine our tactics for defending our class with the strategy of liberating our class. Socialists do not fall into the trap of the ‘progressive’ facade of nationalism. The success of the right-wing Ukrainian and Russian nationalists shows the danger of believing that radical nationalist slogans always lead to radical results. Scottish nationalism does not strengthen the campaign for socialism or create a united, class-conscious working class, but fragments and weakens it.

To those who are in the ‘Yes’ camp, we are saying independence will not improve your condition one iota. Only class struggle could do that and only with difficulty. Any success or otherwise of any workers’ movement in Scotland depends on close ties with similar movements in England (and elsewhere). At the same time, we are not defending ‘British nationalism’ and the unity of the United Kingdom in any way. That would be an endorsement for the status quo, something we do not support. So we do not argue that the present constitutional arrangement benefits ordinary people either. The liberation for Scottish workers can only come about by overthrowing capitalism itself. If this is not done, no amount of separatism can ever succeed in bringing freedom. Instead of tragically wasting time fostering nationalism, workers should be struggling for a socialist society without national borders.

‘Because the condition of the workers of all countries is the same, because their interests are the same, their enemies the same, they must also fight together, they must oppose the brotherhood of the bourgeoisie of all nations with a brotherhood of the workers of all nations.’- Engels, November 29, 1847.