WORLD WAR I – THE CATASTROPHIC RESULT OF IMPERIALIST RIVALRIES

On June 28, 1914, Gavrilo Princip, A Serbian nationalist, assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian empire. This incident sparked World War I, that soon engulfed much of the world and led to the deaths of millions of soldiers, and millions of civilians.

Glorification of militarism

The UK government is using the events around the centenary to glorify militarism and to uphold the British role in the war. The government’s propaganda line concedes that the war devastated an entire generation, and yet it insists the war was a necessary response to the determined effort of Germany to expand its autocratic rule over all of Europe.

This rationale is simplistic and self-serving. The reality was far more complex. Indeed, the UK was instrumental in unnecessarily prolonging the war as it sought to defend its position as the dominant imperial power.

Then, as now, Europe was deeply divided by cross cutting imperial rivalries and the nationalism of a host of religious and language ethnicities. World War I began as a regional conflict in the Balkans, an area where ethnic differences had often led to local wars. The situation was made more explosive by the presence of two conflicting empires, the Austro-Hungarian empire and Czarist Russia. The Austro-Hungarian empire was a loose agglomeration of many ethnic groups with German language Austria at its imperial centre. In an effort to further its presence on the Mediterranean, it had occupied, and then annexed, Bosnia. This act of imperial expansion antagonized Czarist Russia, which was intent on expanding its influence within the Balkans, as a preliminary step to gaining control over the Dardanelles, the gateway to the Mediterranean, then a part of the Ottoman Turkish empire.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand was hardly the act of a single fanatic. On the contrary, this was the result of a carefully organised plot directed by Serbian military intelligence. There is considerable evidence that the Czarist regime knew of the assassination plot before it occurred and gave it, at the very least, its tacit approval.

Thus, the assassination an only be understood in the context of the broader rivalry between the Austro-Hungarian empire and Tsarist Russia. Contrary to the common wisdom, the imperial powers did not blunder unsuspectingly into World War I. During the month of July 1914, in the immediate aftermath of the assassination, the potential combatants put out feelers to assess the situation. The Austro-Hungarian authorities reached out to the British in the hope that the UK would remain neutral.

An Austro- Hungarian official wrote to a key member of the UK government stressing the threat posed by Russia and its role as a protector of Serbia. The official insisted that his government would feel compelled to respond with a military attack even if this involved the possibility of triggering a total confrontation of the European powers. Both sides understood that the localized conflict in the Balkans could easily lead to a wider war, and yet both sides refused to enter into meaningful negotiations that might have led to a compromise agreement that could pull the world back from the abyss.

Total war

Although the conflict began as a local dispute, it soon widened into a total war of the imperial powers. Underlying the war was the rise of Germany as an economic and strategic power. In the era prior to World War I, the UK reigned as the foremost military power. Its control of the seas allowed it to exploit inexpensive raw materials and valuable resources, providing the basis for enormous wealth and an advanced industrial base. Germany’s rapid industrialization challenged the UK as an economic competitor, while the creation of a strong army meant that Germany became the most powerful military force in continental Europe.

Germany’s rise to power was also viewed as a threat by its two imperial neighbours. By the 1890s, Russia and France had entered into a military alliance, the Entente. Germany responded by developing closer relationship with the Austro-Hungarian empire. The British empire had frequently collided with Russia as both sought to expand their empires into Asia.

Nevertheless, the prevailing sentiment within the British ruling class was that Germany posed a dire threat to the empire. This sentiment hardened as Germany cultivated closer ties with the Ottomans, thus blocking the British drive to control Middle Eastern oil. By 1905, the UK had overcome its historic hatred of France, and its contemporary rivalry with Russia, to become an unofficial member of the Entente.

Thus, on July 29, 1914, when the Austrian army began shelling Belgrade, the capital of Serbia, the conflict escalated rapidly from a localized battle to a global total war. Once Russia mobilized its troops to defend Serbia, the Germans knew that the French would soon join Russia as an ally. Germany then acted pre-emptively, attacking France and occupying Belgium. The UK then declared war on Germany and the terms of the conflict were set.

Tinderbox

There is little point in attempting to determine which side bears the primary responsibility for starting World War I. Europe in 1914 was a tinderbox. A conflict over Morocco had already nearly drawn Germany and France into war in 1911. Both sides refused to negotiate a meaningful compromise and both sides understood that this meant that a total war was a significant possibility.

At first both sides cultivated the illusion that the war would be a short one. As the war quickly reached a stalemate, these illusions were shattered. Within a few months after the war had begun in August 1914, the German government realized that it had committed a disastrous blunder by entering the war. The UK government was intent on destroying Germany as a military threat and determined to force it to unconditionally surrender. Furthermore, Britain and its allies signed a number of secret treaties dividing the potential spoils, treaties that could only be implemented once a total victory was achieved. The UK was intent on gaining control over Middle Eastern oil.

Creating a famine

During the four years of the war, both sides engaged in horrific acts of brutality. The Germans introduced poison gas into modern warfare, and the Ottomans conducted a genocidal campaign against its Armenian minority, leading to the deaths of 1,500,000 innocent civilians. On the other side, the British instituted a strict naval blockade that included foodstuffs as contraband. This was done with the deliberate aim of creating a famine.

As casualties mounted, popular pressure for an immediate peace intensified. The German government began looking for a way out, indicating a willingness to withdraw from occupied France and Belgium. Yet the UK government refused to enter into negotiations with Germany, insisting that the war be continued until a decisive victory was won. This adamant refusal was a crucial factor in prolonging the war. Once the United States was persuaded to enter the war as an ally of the UK, and US troops began fighting in the trenches, a German defeat was certain.

Enormous impact

World War I had an enormous impact on the course of world events, an impact that is felt to this day. The defeat of the Russian army lead to a popular revolt in March 1917 and to Lenin’s Bolsheviks coming to power in November 1917. When the war ended in November 1918, the UK and its allies dictated the terms of peace at Versailles. One element in the peace treaty was the artificial creation of Iraq, which was placed under British control. A century later, Iraq is disintegrating into sectarian warfare.

As we remember World War I we need to keep in mind the catastrophic consequences of imperialism. A century ago, the UK was the dominant power and the United States was just beginning to assert itself as a world power. The situation has since been reversed, as the UK is reduced to a subordinate role in an alliance with the United States.

Through NATO, Scotland provides the United States with military bases that it uses to launch attacks. We need to raise the demand: SCOTLAND OUT OF NATO.

Eric Chester (RCN)

NATO IS DEAD – WHY JOIN IT?

Two years after the SNP’s historic vote for a future independent Scotland to remain a member of NATO, what has changed?

The UK’s membership of NATO has been successfully kept off the political agenda since joining, apart for one discussion at a Labour Party Conference in the early 1980s. The level of understanding about the consequences of staying a member remains low and is wrongly understood as secondary to domestic issues. Only two nationalist MSPs felt strongly enough about the change to resign.

Although NATO membership briefly intruded on the political agenda for the left this has been swept aside by concern over austerity cuts and future Scottish national identity. This has suited the political and military elites. For decades, according to Professor Malcolm Chalmers former Director-General of the Royal United Services Institute membership has “given [the UK’s] elites the self-confidence to make a disproportionate contribution to international governance.”[1]Emancipation & Liberation Issue No 21 Winter 2012 The Slippery Slope Salmond’s strategy is to keep that continuity in place.

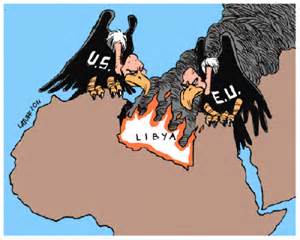

NATO is not the unified, disciplined military command it was during the Cold War but has attempted to become a pool out of which a “coalition of the willing” could be assembled for more limited Out-of-Area Operations. However, the intervention in Libya was a disaster and NATO was discarded when plans for involvement in Syria were being made. The Libyan intervention was essentially the death of NATO even if the corpse still twitches.

Serious tensions

France had withdrawn from NATO’s integrated military command in 1966 only to rejoin in 2009. Immediately, it sought leadership of the organization over activities in the Middle East and Africa seeing the US’ “pivot to Asia” as a limited withdrawal from these areas. Serious tensions arose between France and the US, and Italy, Germany. Eventually, Germany and NATO’s most important member in the region.

Turkey also opposed the intervention. “Few dispute the assertion that NATO jets enabled the Libyan rebels to come knocking at Qaddafi’s door in Tripoli,” assessed Professor Michael Clarke, Director-General of the Royal United Services Institute, “But as he falls, it will be difficult to avoid the conclusion that NATO emerges from this successful operation weaker than it went into it.”[2]The Slippery Slope It was a disaster the US did not want to repeat over Syria. And it will happen again in other areas.

NATO may be a “nuclear alliance” that creates an umbrella where non-nuclear states may seek to shelter. But it is also an organisation of political approval and a powerful economic force. These are the main reasons that many countries join. NATO has around 1,300 standardisation agreements that create the basis for numerous massive international contracts for not just warships and jet fighters but boots, uniforms, water bottles, catering and other products and services. Gaining or losing these contracts can have an enormous effect on some countries especially during periods of so-called austerity.

Applications refused

The Soviet Union applied for NATO membership in 1954, and the Russian Federation during the noughties. Their applications were refused. NATO is not simply defined by the countries that join it, but also by who it refuses. It creates a ready-made list of friends and enemies, even when those friends have been at war with each other such as Greece and Turkey and reinforces US supranational legislation prohibiting trade with Iran, Sudan and revolutionary Cuba. NATO membership makes impossible a real independent foreign, economic and military policy. The existence of “exclusive” military pacts is prohibited by the United Nations. A future independent Scotland should include this as an important article in any national constitution,

Though the left has failed to understand the consequences of NATO membership let alone build a campaign against the organisation, the issue has at least been raised. Concerns have not disappeared either. As commemorations about 1914-1918 conflict are remembered, it is to be hoped that a better understanding of imperialism’s current military arrangements can be developed.

Murdo Ritchie (RCN)

REMEMBERING THOSE WHO RESISTED WAR

Whilst the ruling class seeks to glorify World War 1, minimising the suffering of hundreds of thousands of soldiers butchered in this slaughter; it is worth noting the hidden history (or in some cases her story) of brave people who resisted this needless butchery.

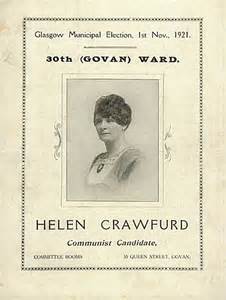

Helen Crawfurd was in the militant wing of the suffragettes and was the wife of a Church of Scotland Minister. She compared her actions to those of Jesus driving out the money lenders from the temple. She was moved by speakers like Keir Hardie and was outraged at Christabel Pankhurst speaking for the war, so she heckled her shouting “Shame on you!”

The anti war movement began in Scotland in 1914. It included the Independent Labour Party (official Labour was pro war), No Conscription Fellowship (including the Quakers who supported people who didn’t want to fight), Union for Democratic Control, Christian pacifists, Labour women’s movement re aligned with pacifist feminists, arguing after the war against the notion that women were only given the vote for supporting the war.

The Women’s International League (WIL) saw the militarising of the British state for war, talking of the gendering of war and arguing that only women could build peace and educate their sons not to fight in wars.

Meanwhile the Clydeside women led by Mary Barbour organised rent strikes and worked with shop stewards at the local shipyards. Helen Crawfurd realised the WIL were not in tune with working class women, so advocated similar tactics to union men; which led to a 5000 strong demonstration on Glasgow Green in 1916.

The 1917 Russian revolution gave peace campaigners more heart and activity stepped up. Meetings heard personal stories from bereaved wives whose husbands had been at the front. A “Peoples Peace Manifesto” was written which made several demands for peace.

Mary Barbour was from Renfrew and moved to Govan. Housing was a problem, particularly when landlords took the opportunity to hike up rents. Mary was the chair of Govan Housing Association and helped organize rent strikes. Signs were put in windows saying, “We’re refusing to pay” which led to legal actions and evictions.

Women rang a bell to alert each other when sheriff’s officers arrived, who were stopped by the women known as Mrs Barbour’s Army. Noisy demonstrations followed 18 evictions in Patrick. Mary got shipyard workers to help get back money for a woman who’d been tricked into paying. Eventually Lloyd George intervened with the Rent Restrictions Act and evictions were stopped. This was the biggest success for the working class in Scottish history and boosted the anti war movement.

Chrystal Macmillan was a suffrage campaigner, was in the National Union of Women Workers and elected Secretary of International Women’s Suffrage Association. With others she wrote the “International Manifesto of Women” in July 1914, starting with “We the women of 26 countries appeal to you to end war” signed by Chrystal Macmillan and Millicent Fawcett, and delivered to all the embassies in London. Despite difficulties with travelling, a Congress of Women went ahead in Holland in 1915.

Poverty, education and equality were addressed and a plan of action for permanent peace was put in place. They met a King, the Pope and other dignitaries to try to organise a peace and disarmament conference with neutral nations. Unfortunately the neutral nations were too afraid and it didn’t materialise.

John Maclean of course was a campaigner against war who was imprisoned several times for “sedition” meaning his opposition to war. He was force-fed food, which he believed was poisoned, in an effort to break his health and spirit but was always applauded and well respected by the working classes of Glasgow.

Pauline Bradley (RCN)

References

| ↑1 | Emancipation & Liberation Issue No 21 Winter 2012 The Slippery Slope |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Slippery Slope |

Interesting article. Imperialism was certainly the major underlying cause of WW1. But there were also other causes such as the need for Europe’s ruling classes to contain threats from the working class through nationalism and war. As Marx said: Governments use war as a fraud, a ‘humbug, intended to defer the struggle of the classes’.

This ruling class strategy is explored here:

World War I and 100 years of counterrevolution

https://libcom.org/history/world-war-one-100-years-counter-revolution-mark-kosman