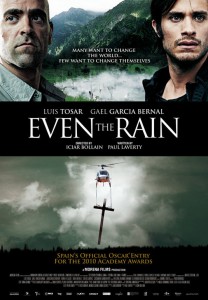

Paul Laverty’s Even the Rain is a very powerful film that works on several levels. As a piece of drama, with a compelling musical soundtrack, it captures and holds your attention. You would not have to be politically engaged to enjoy this film. However, for anybody at all concerned about the present state of the world, and the inspiring growth of challenges to the global corporate order in South America, this is a must-see film.

The film begins with two Spanish film-makers, Sebastian and Costas, recruiting a cast from amongst the local Quechua Indians of Cochabamba in Bolivia to make their own film. This film-within-a-film is to be about Columbus’ conquest of the Tainos Indians in Hispaniola; and two Dominican friars, Antonio de Montesinos and Bartolome de Las Casas, who attempted to challenge the brutal behaviour of the Spanish conquistadores. This film’s director, Sebastian, has been greatly affected by his personal discovery of La Casas’ unsuccessful appeal to King Philip of Spain. In protest at the sheer brutality of the treatment of the Indians, Las Casas held to the view that, “All people of the world are humans.” Sebastian sees this as having a strong contemporary relevance.

However, the producer, Costas, has chosen Bolivia for the film-shoot, because it has the cheapest labour in South America. Furthermore, in order to make the film, it is the official Bolivian and Cochabamba authorities, still dominated by the descendants of the original conquistadores, who Costas and Sebastian deal with. Early on, whilst enjoying themselves, eating and drinking in conditions of some luxury, the principal Spanish actors in this film become engaged in arguments about the nature of the Conquest, and about Columbus, Montesinos and Las Casas. However, as the main film proceeds, the limitations of conservative versus liberal sentiments becomes very clear. By the end of the film, the original participants in these arguments adopt quite different positions.

For what makes the fortunes of this particular planned film different from other films, using ‘Third World’ settings and low-cost local casts, is the dramatic intrusion of external events. In 2000, a massive protest emerged in Cochabamba. This involved the local Quechua population struggling against the Bolivian government’s attempt to enforce water privatisation. A joint British, Italian, US and Spanish consortium, Aguas del Tunari, was given monopoly control of Cochabamba’s water supply under the World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Programme. The main film shows how the Bolivian state starts to enforce the company’s monopoly by getting the local police to padlock the people’s wells. Initially, only Maria, Sebastian’s assistant, understands the wider significance of these events, and wants to devote time to making a film about them.

Meanwhile, Sebastian and Costas have recruited Daniel, a local Quechua Indian, to play the role of Atuey, a key leader in the failed Tainos revolt against Columbus and Spanish rule. However, whilst impressed by Daniel’s forceful character, they do not initially realise that he is a prominent activist in the Cochabamba protests. Even the Rain is largely made in the Spanish language, although the sub-titles hardly detract from the unfolding drama. However, when Costas resorts to the English language so that Daniel won’t understand what he says, he reveals his own prejudices. Daniel has worked in the USA, and understands English – as well as speaking both Spanish and Quechua. From then on the central dramatic narrative of the film turns on Costas’ and Daniel’s changing personal relationship.

The Bolivian government’s clampdown on the massive protests in Cochabamba increasingly impinges on the making of Sebastian and Costas’ Columbus film. The completed scenes from this film are powerful in themselves. However, the Quechua women actors refuse to finish a scene which would involve them showing the drowning of their babies to avoid them being ripped to pieces by the conquistadores’ hunting dogs. Meanwhile, Daniel’s daughter, Belen (who has been given an important role in the Columbus film as Panuca) and his wife, Teresa are shown actively involved in the water privatisation protests. Costas and Sebastian become more and more aware of the contradictions of trying to complete a film showing the historical inhumanity of the Spanish conquest, whilst Daniel and Belen, in particular, become subjected to the contemporary brutality of the Bolivian government and Cochacamba authorities.

The dramatic highpoint occurs when, during the making of the Columbus film, the conquistadores burn Atuey and other Tainos at the stake. Las Casas beseeches the conquistadores not to go on with the burning, because it will show the Catholic Church in a bad light, and make a martyr out of Atuey. This has no effect, highlighting the limitations of such liberal appeals. However, this is immediately followed by the direct action of the Quechua Indian actors, when they overturn the police car, sent to the film-set to arrest Daniel. Daniel is set free to continue the anti-water privatisation protest, which results in a notable victory.

The last scenes of the film concentrate on the relationship between Costas, Teresa, Belen, and Daniel. Indeed, it is the personal transformation in Costas, under their influence, which gives this film a wider appeal, as his own values are challenged and begin to change.

However, for socialists there is also the very strong political message in this film. There are no depths to which corporate capital and its imperial backers will not stoop. The film’s title, Even the Rain, makes this clear. They would even deny people access to life-giving water in order to make a profit. Nowadays, we are witnessing a massive extension and imposition of the Structural Adjustment Programmes, long practised in the ‘Third World’ – most obviously in Greece. However, this film shows a key turning point in the beginnings of the rise of continent wide protest against US imperialism and the activities of the global corporations, the IMF and World Bank. Hasta la Victoria Siempre!

Allan Armstrong, 21st May 2012

(An edited version of this review first appeared in Scottish Socialist Voice, issue 396.)