Reprinted from Issue no. 64, Nov/Dec 2005, of Class Struggle, produced by the International Communist Union (Trotskyist)

More than 5 years ago, on 7 May 2000, British troops landed in Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone. This was the first major intervention by the British army in sub-Saharan Africa since the end of its bloody campaign in Kenya, in 1964.

At the time, Blair’s government claimed that its only aim was to rescue British citizens whose lives were allegedly threatened by a rebel offensive against the capital. This pretext sounded rather hollow, however, in view of the many similar offensives which had already taken place since the beginning of the country’s decade long, on-going and brutal civil war. In fact, within days, Blair was explaining that the army would need to stay for at least a month, to facilitate the build-up of a UN peace-keeping contingent. Soon, however, this one-month mission was extended to a 9-month, during which the British contingent became actively involved in the war, under the pretext of ‘helping’ UN troops to disarm the rebels.

Two years later, when the new rulers, brought to power by London, declared the civil war officially over – whatever this really meant on the ground – a British contingent was still there. And far from pulling out, part of it stayed on, this time on an open-ended mission, ostensibly aimed at training a new Sierra Leonean police force and army.

Five years on, the British forces are still in Sierra Leone. Officially, Britain is now only providing advisors and ‘army trainers’. But their real function is certainly better reflected by the fully manned British warships which are constantly anchored off Freetown’s shores, ready to fulfil Britain’s commitment to deploy its forces within 48 hours, if needed. Blair, who boasts of have restored ‘peace and democracy’ in Sierra Leone, has never bothered to explain why such an idyllic state of affairs should require a heavily armed task force on the ready. Obviously, just like in Iraq, the interests of imperialism in general and British capital in particular have something to do with it.

While thanks to Blair’s military venture, western companies are in a better position today to take the lion’s share of the country’s natural resources, the population of Sierra Leone has gained nothing – except the right to return to the ruins of a country devastated by the civil war and to slide even further into poverty as a result of the systematic looting of the country by imperialism.

A civil war fuelled by poverty and western plunder

It should be recalled that civil war in Sierra Leone began in 1991. As is often the case in sub-Saharan Africa, because of the artificial nature of the national borders inherited from the colonial days, this war started as an offshoot of another civil war, which had been fought on and off in neighbouring Liberia, for more than 8 years.

As in Liberia, the cause of the civil war in Sierra Leone was a combination of three factors: the catastrophic slide of the population into poverty since the mid-1970s, the collapse of the corrupted western-backed cliques in power and the resulting implosion of the state machinery itself, particularly of its backbone, the army.

During the total 11 years of civil war in Sierra Leone, the capital, Freetown, changed hands no less than nine times – and each time, so did the nominal rulers of the country.

At its peak, the war involved 4 main local armed factions. Two of these factions – the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) and the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) – had been set up by young nationalists and former army officers in an attempt to bid for power. Another faction was the rump of the regular army, although it was itself divided into many rival sub-factions, as many unit commanders tended to have their own agendas. The fourth faction, the so-called Kamajors, was a British-backed tribal militia.

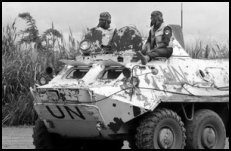

This war also involved a large number of ‘official’ foreign troops. The first foreign contingent to intervene, in the early 1990s, was the Nigerian-led ECOMOG, a multinational force originally set up under western pressure by the Economic Community of West African States, to intervene in the Liberian civil war. However, throughout the war, acting more or less behind the scenes, under the auspices of the western powers, were small armies of highly-trained, heavily-armed mercenaries, provided by organisations such as the British based Sandline and the South-African-based Executive Outcomes. With the intervention of the British army in 2000 and the subsequent build-up of the UN’s 17,500-strong UNAMSIL contingent, the total number of more or less independent protagonists in the war rose to seven, not counting the various mercenary outfits.

Predictably, apart from Freetown itself, much of the war was fought over who would control the country’s main natural resources – its diamond fields and rutile mines (Sierra Leone has the world’s largest known deposits of this mineral, from which titanium is derived, and used in the manufacture of paint and special alloys).

For the Sierra Leonean population, the particular uniforms worn by the soldiers did not make all that much difference. All these forces behaved in the same way, with the same aim – to terrorise the population into backing them. The foreign troops had aircraft and helicopters, whereas the local factions did not. The former avoided direct contact with the population, whereas the latter systematically forced young boys to join their ranks. But ECOMOG’s rifles and incendiary grenades or the anti-personnel bombs of the British and the mercenaries, caused as many casualties among the villagers as the machetes of the local factions.

London’s ‘solution’

By 1996, taking opportunity of another coup led by a general who was willing to toe the western line, the western powers pushed forward their own chosen strongman. This was Ahmed Tejan Kabbah, a seasoned politician and former UN official. In 1996, during a relative respite in the war, a presidential election was organised at Britain’s behest and Kabbah was elected. This election was a farce, as large parts of the country were held by the rebel factions and did not take part in the vote, while 25% of the population had taken refuge in neighbouring Guinea. Nevertheless it allowed the western leaders to portray Kabbah as a ‘democratically elected leader’ and to provide him and his Kamajors militia with their political and military support.

However Kabbah had no real basis of support among the population, let alone among the remaining ‘official’ Sierra Leonean army. He was soon overthrown by a military coup and forced into exile. And his two subsequent attempts to resume his position in Freetown met with the same failure to restore some order in the country, despite the protection of ECOMOG, the Kamajors, the various mercenary forces as well as the first contingent of ‘peace-keepers’ sent by the UN.

It was this failure to maintain Kabbah in power which prompted Blair to send the troops in 2000 – all the more so as, the last thing he wanted, of course, was to leave the country, which was after all part of the traditional backyard of British capital, in the hands of a US-dominated UN!

In fact British ‘advisors’ had been occupying every level of Freetown’s administration – from the military to revenue and finance – since Kabbah’s second return, in 1998, with Keith Biddle, formerly of the Greater Manchester and Kent police forces even acting commander of the Sierra Leone Police. Hardly surprising that many commentators now claimed that Britain was resuming colonial control of the country.

Finally, after a new agreement was signed with the various factions, a second ballot was held in 2002 in which Kabbah was ‘re-elected’ by a ‘landslide’ in ‘free and fair elections’, even if much of the population was still in refugee camps or internally displaced and unable to register to vote.

Today, the war is said to be over. The UN troops have been reduced to 3,000 and are due to leave the country by the end of this year – although no date is set for the departure of the British task force. But has ‘normal life’ been even partially restored by this huge outside intervention? What about the 50,000-200,000 victims of the war (nobody really knows how many) out of a population of less than 6m? What about the barbaric mutilation suffered by civilians as a result of rebel factions’ ‘special’ punishment, which took the form of amputations of their hands, feet, arms and legs? Do these victims all now have artificial limbs and medical care, or even schools, hospitals, roads, water, electricity? Do they all have homes to live in?

The answer is no.

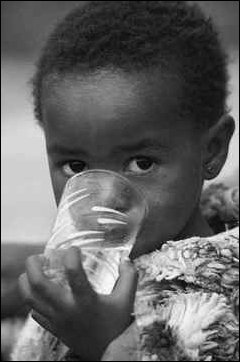

Statistics show that today, 70% of the country’s population are living in extreme poverty. That average life expectancy is 37 years, supposedly up from 34 years in 2003; infant mortality is 70 times higher than in Britain. Only 36% of the population can read and write yet still only 40% of children attend school. Only half the population has access to clean drinking water, etc.

In fact, after having been ranked as the world’s poorest country (177th rank) for seven years in a row by the UN, Sierra Leone has managed to climb to 176th rank this year, but only as a result of Niger’s acute famine crisis!

Such is the great ‘success’ achieved by Blair’s on-going military intervention. But even this is only part of the picture. The truth is that the entire country, with most of its infrastructure, has been destroyed and nothing is done about it.

No plans for the population

What Blair means by restoring ‘peace and democracy’ in Sierra Leone certainly does not include making plans to meet the needs of the population, let alone implementing them – British imperialism has only contempt for the masses, whether in Sierra Leone or in Iraq.

Electricity supply provides a graphic illustration of this. There are only three places in the whole of Sierra Leone which get 24-hour electricity, all in and around Freetown: the government’s complex, the British army compound and UNAMSIL-ville, the UN compound.

As to ordinary households, they are lucky if they get electricity one hour per week! Nevertheless, they do receive electricity bills. And the National Power Authority actually increased charges for the second time this year in October, by 30%, without first notifying anyone!

The problem is that the infrastructure managed by the National Power Authority is in a near terminal state, despite cash injections from donor states, like $10m from South Africa. Freetown’s only oil power station cannot even provide half the capital’s requirement, in spite of recent upgrading. And then, there is the state of disrepair of the distribution network, resulting in massive energy losses.

The power supply problem is to be solved however, but not quite yet! The World Bank only approved a grant of $12.5m in June this year to finance the Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project, intended to supply Freetown, in particular. So, although this project was originally meant to be completed by October 2005, construction will only start next year. In the meantime, the South African state power utility, Eskom Holdings, is in talks to take over management of the National Power Authority, undertake refurbishment and provide technical support – but this will not come for free for consumers, of course.

To make up for the erratic supply of electricity, the people who can afford it, buy little generators – known ironically as ‘Kabbah Tigers’ – which cost 160,000 leones, or around £32 (£1=5,000 leones). But the ‘legal’ (if this means anything) monthly minimum wage is £7.50! Which will not buy a sack of (imported) rice! So even owning an inefficient ‘Kabbah Tiger’, worth the equivalent of nearly 5 months wages, is the privilege of the relatively ‘rich’, just as buying the low-grade fuel used to power these generators as well as all vehicles, at around £2/litre from mostly illegal suppliers over the Guinea border.

The country’s road network is another case of total disregard for the needs of the population. Whole sections of roads are still destroyed, having been blown up during the war, or, simply, for lack of repairs for over a decade. As a result, agricultural products from the rural areas cannot reach the capital where they are need. While food prices are going through the roof in Freetown, threatening the poorest with starvation, rural farmers can hardly scrape a living. But there is no question of using the Navy’s idle heavy-duty helicopters to carry food supplies into the capital until the roads are repaired, nor has the Royal Engineer Corps been mobilised to repair these roads!

Neither have the western forces mobilised their resources to put together a refuse disposal system in the capital as a matter of urgent health and safety. Today, vast mountains of uncollected rubbish are piled up all over Freetown. In a satirical stab at the City Council, a local paper, the Concord Times warned:

Freetown residents are at present working towards setting up a Special Court to try all those who bear greatest responsibility in keeping the city filthy. Those whose efforts have brought the battalion of flies and mosquitoes to inflict mayhem will be tried come 2007 when the court starts sitting.

This being an allusion to the UN Special Court meant to prosecute those bearing ‘greatest responsibility’ for war crimes – and to the coming elections in 2007, when the population will have a chance to pass its judgement on the present regime.

Meanwhile, in Freetown, an army of expensive 4x4s, driven by UN, NGO or British personnel, are pushing their way to the front of the queues of the local mostly unroadworthy vehicles and flaunting their privilege by raising clouds of dust in the faces of the majority who have to walk everywhere they go, not always on two feet and certainly without shoes.

The ‘rebuilding’ of Freetown

However, UN and British forces do contribute in their own way, to the ‘rebuilding’ of the capital by generating a flourishing ‘industry’ – prostitution – to which many young women resort for lack of any other means to survive.

So far, this ‘industry’ has resulted in numerous extremely nasty scandals, as a consequence of the way in which successive units of soldiers from all over the world have regularly sexually exploited vulnerable and impoverished women and girls.

Strangely enough, even though £20m was allocated by the UN towards HIV/Aids projects, there are no statistics as to the incidence of infection – although it is thought to be around 7% of the population. Which merely reflects the fact that there is nothing which even vaguely resembles an organised health care sector.

Of course, UNAMSIL has been forced to recognise its corrupting influence. It recently launched a project dubbed ‘girls off the street’ to cut down the rate of prostitution. The project aims to train these girls as commercial transport drivers and motorcycle riders to ‘transport goods and persons’ around the country. However, the UN’s contribution exposed the cynicism of its alleged goodwill: two taxis, some motorbikes and around 2m leones which is equivalent to around £438!!

It is not just women who are being exploited under Blair’s occupation of Sierra Leone, children are as well. Of course, child labour is a common feature in most poor countries. But it reaches an extreme in the streets of Freetown, where little children, bare-footed, sickly, and in rags, try desperately to sell a handful of nuts, fruit or corn, or a carefully tied plastic bag of water, origins unknown – because access to drinkable water is another unresolved problem.

Other small children who cannot be more than ten years old sit by the roadside, armed with hammers, breaking large pieces of granite into smaller pieces. This child labour is, among other things, an essential contribution to Freetown’s ‘booming’ building industry! These children must load the broken gravel into baskets and strain their puny neck muscles to carry this weight on their heads to the sites where higgledy-piggledy housing is being erected – without any regulation – because access is by foot only, for lack of a proper road.

Three years after the war was declared over, many houses still stand in ruins, shelled, burnt, marked by gunfire, in any case in bad need of refurbishment, if not complete reconstruction. But the construction work which is being done is not for the poor population. This construction is largely being undertaken by Chinese companies, with a boldness to jump in where other countries fear to tread

as the British Financial Times remarked upon in their survey of Sierra Leone published in February this year.

For instance there is the refurbishment by the Beijing Urban Construction Group of the 60,000-seat national stadium complex, the government complex and the army headquarters… One should also mention the 11-acre Bintumani Hotel site, where a ‘Chinese themed’ upgrading continues (on a 25-year lease signed with the government) which includes the construction of a big casino. Another 250-bed luxury hotel complex and conference centre is to be built according to an agreement signed with the Sierra Leone National Tourist Board, in May 2004, as well as a sports stadium in the southern provincial capital of Bo – ‘spectacular’ buildings which will do nothing to solve the housing crisis for the poor.

Under the legalistic fig leaves

Last June, the UN’s Special Court started trials for those accused of war crimes – supposedly, those who bear ‘the greatest responsibility’ for organising atrocities since 1996. Only 13 people were indicted. But, among them, 2 are already dead, one is missing and another, the Liberian warlord Charles Taylor, has been given political asylum in Nigeria. So only 9 accused will be put on trial. Yet this Special Court has managed to spend $81m in 3 years, much to the disgust of a destitute population, when such funds could have been spend on clean water, housing, health care, etc…!

Ironically, one of the first accused to stand in the dock was not a rebel faction leader, but a member of Kabbah’s government, who was indicted as co-ordinator of the pro-Kabbah Kamajors militia. Needless to say, this helped make the Court’s American chief prosecutor extremely unpopular with the regime and he has now decided to stand down. But then, of course, this court, like similar tribunals in Rwanda, is primarily there as a fig leaf aimed at putting all the blame on just a few individuals, while deflecting scrutiny from those in power.

The parallel South African style ‘Truth and Reconciliation Commission’ has a complementary purpose. It grants amnesty to the accused in return for a ‘confession of guilt’, thereby, no doubt, allowing these individuals to be recycled into respectable figures who can then be co-opted by the regime, regardless of their past crimes. This legal charade is all the more cynical because, at the same timeas these sanctimonious proceedings are progressing, the country is sliding into a corruption swamp, despite the appointment of various anti-corruption bodies.

Corruption is legendary in Sierra Leone, as it is in so many poor countries. Today’s British-backed regime is no exception. With diamonds and other attractive minerals involved, there is huge scope for personal gain, including from the granting of mining and prospecting licences. According to a twice weekly local publication called Peep! which exposes misuses of power, Things have gone from bad to worse, ironically since the Anti Corruption Commission has started!

This is confirmed by the executive director of the ‘National Accountability Group’ who is quoted as saying: If you’re put in a government office and you don’t steal, your whole family gets angry with you

. And the conspicuous wealth flaunted by government officials, which is certainly not commensurate with their salaries, is even more sickening in the context of this devastated country. However, exposing the reality of corruption is a dangerous thing to do under president Kabbah.

Actions against journalists have been going on for some time. In 2002, the daily African Champion Newspaper was shut down for 2 months and its editor banned from journalism for 6 months, for accusing Kabbah’s son of corruption and claiming he was protected by his father. The same year, Paul Kamara, editor of the newspaper For Di People was jailed for 2 months and his paper banned for 6 months for calling an Appeal Court Judge a swindler.

Last year, Paul Kamara, again, was given a 4-year jail sentence for slandering the president. He had claimed that Kabbah should not have been allowed to stand for president, since his name had never been cleared of a fraud scandal, which took place in the late 1960s, when he was permanent secretary at the trade ministry.

Far worse even, the acting editor of For Di People, Harry Yansaneh, was beaten up in July this year by thugs allegedly acting on the orders of a ruling party MP. He later died of his injuries. His murderers were found guilty of homicide, but were then somehow freed on bail. So much for Kabbah’s Blair sponsored ‘democracy’!

Open for business

As in most poor countries, the only game in town for the regime is to attract foreign investment. So, despite the county’s general economic bankruptcy and deprivation, Kabbah relaunched the privatisation drive interrupted by the war. Plans have been drawn up to sell off 24 state-controlled companies, including finance, transport, utilities and commerce. The target for completion, originally 2006, is now 2010, while the Commission in charge of the job complains that it would require at least $12.5m in ‘sweeteners’ in order to attract buyers. As a result, the only candidate for privatisation, so far, is the Rokel Commercial Bank – which was formerly owned by Barclays, until it sold it to the government for a nominal £1, in 1998. But since this bank was put up for sale in December 2004, there have not been any takers.

To make the country even more attractive to potential ‘investors’, the Sierra Leone Export Development and Investment Corporations, shortened to a catchy ‘Sledic’, offers them a 7 day fast track registration. Foreign companies are offered an attractive package devised with the help of the World Bank. For instance, investors in large-scale agriculture get a 10 year exemption from the standard corporate tax rate of 35%, with no minimum capital requirements. Besides, materials required for ‘tourism businesses’ and equipment for mining operations are duty-free.

Only a few areas have so far attracted the interest of foreign companies: mobile telecoms (!), agriculture and fisheries, rutile and, of course, diamonds. Mobile telecoms has the advantage of requiring only minimal existing infrastructure, which is why this industry has been blossoming right across Africa, where it has often replaced fixed lines. However, in Sierra Leone, even this minimum barely exists. As the manager of the main mobile operator, the Kuwaiti-owned company Celtel, complains:

Energy supplies are getting worse, so we have to run two generators at every site. Then we have to run a fleet of 20 vehicles on the worst roads in Africa…

As for agriculture – this is a Kabbah’s big headache, since he promised that every single person in the country would have enough to eat by 2007. He has since qualified this by saying he had not meant that he personally was taking responsibility for feeding everyone! Just as well, since the initiative to prop up cash crops like coffee and cocoa, is certainly not going to feed anyone at all. That said, rice production, in which Sierra Leone used to be self- sufficient, is supposed to be improving.

The really big business, of course, is in rutile and diamonds. Rutile used to be the country’s biggest export earner before the civil war – although no-one knew for sure, since an unknown part of the diamond production was smuggled out of the country – and the Sierra Rutile Limited used to be the country’s largest employer. Today, all of Sierra Leone’s rutile operations, together with its smaller bauxite resources, have been regrouped into the Titanium Resources Group, a London-listed company, controlled by a very shadowy business character -Jean Raymond Boulle, a British citizen based in the French tax haven of Monaco. Boulle’s name has been associated, one way or another, with just about every recent African civil war in which mining resources were at stake – such as Angola and Congo-Zaïre, for instance.

Under Boulle’s auspices, Sierra Leone’s rutile mines were reopened officially at the beginning of November, thanks to EU and US loans. Full production should resume later this year. As to diamonds, last year’s outputreached 32% of the 2m carats which used to be produced annually in the 1960s. While small scale digging of the alluvial diamond deposits has resumed, Koidu Holdings is the only ‘industrial scale’ diamond mining operation exploiting the Kono diamond fields in the north east at present. In fact, Koidu Holdings is just a front controlled by what was formerly Branch Energy, the British-based company linked to the mercenary outfits, Executive Outcomes and Sandline. Jan Joubert, the South African chief executive of Koidu Holdings, admits himself that, together with some of his staff, he used to work for Executive Outcomes. It seems that in exchange for the ‘services’ provided by the mercenaries to the Kabbah regime, the 25-year lease obtained for the Koidu area as well as exploration licences for gold and diamonds elsewhere are finally bearing a lot of ripe fruit for these soldiers of fortune and their corporate sponsors.

There are still others are in the diamond game. The British-Canadian company Mano River Resources is said to be close to entering a joint venture with mining giant BHP-Billiton to blast out diamonds in Kono. In addition, the Sierra Leone Diamond Company claims to have 20 mineral prospecting and exploitation licences for the entire northern third of the country covering a total area of 36,365 square kilometres. This company has an address in London’s Berkeley Square, is registered in Bermuda and is controlled by another shadowy businessman – Vasile (Frank) Timis who has been accused of all kinds of nefarious dealings to do with Regal Petroleum and mining operations in his native Romania.

However, behind the (relatively) small players of the diamond industries, the real big beneficiary remains De Beers, simply because of its 50% control of the diamond market.

The rutile and diamond industries are usually hailed by all and sundry as the future for Sierra Leone. However, not only do they provide no benefit whatsoever to the Sierra Leonean population (except for the handful of local capitalists and politicians), but they are a real calamity for the population of the large areas concerned.

In the case of rutile, for instance, the mineral is mined by ‘dredging’ – i.e. by flooding large areas with artificial lakes and extracting the mineral from these lakes. And the regime connives with the companies to confiscate the lands of local farmers who are left without any compensation. This is probably why the Boulle’s company is officially allowed to maintain a heavily-armed, uniformed private army to guard its operations… against the population!

In the case of diamonds, the 4,500 people who live close to the Koidu kimberlite pipe that Koidu Holdings started blasting two years ago, have to evacuate their homes whenever blasting is taking place. But to date, they have still not been offered resettlement (only 10 substandard, incomplete houses have been built without any facilities), Sierra Leone despite a 2-year long campaign against this company’s destruction of their environment and disruption of their farming activity and their lives. Which is no surprise, of course.

The explosive factors remain

So what is the balance sheet today for the population after 5 years of British intervention and 3 years of ‘peace’ in Sierra Leone? What do Sierra Leoneans have the British government and the UN to thank for? It is hard to avoid parallels with Iraq under occupation and particularly the occupation of southern Iraq by the British.

Kabbah’s regime would certainly not have come to power nor survived until this date without the western intervention and the continuous presence of British troops. Nor would it have any chance to remain in power for any length of time without the 9,000 plus police trained by the UN and equipped jointly by the UN and Britain, or without the new Sierra Leonean army trained and equipped by Britain.

Even then, the ‘peace’ – meaning only political stability at the top – is far from guaranteed. While over the past 3 years there has been no visible sign of a significant-scale armed rebellion, there has been at least one unsuccessful attempt by armed men to break into an armoury in Freetown. And it is probably not for nothing that the new British-trained army chief of staff felt it necessary to tell his officers just this October that they had better stay out of politics, forget their tribal loyalties and where they come from, or resign.

Obviously, coups by disgruntled or ambitious army officers are far too common an occurrence for anything to be taken for granted. Whether the present status quo will be maintained is an open question, especially given the instability of the whole region. After all, nearby Ivory Coast is in turmoil and the recent election in neighbouring Liberia may well only conceal an on-going stand-off between rival armed factions.

As to Kabbah’s regime, after only 3 years of existence, it already has all the features of the old corrupt dictatorships of the past. This does not stop Blair from boasting of having brought ‘peace and democracy’ to Sierra Leone, just as US leaders claim forneighbouring Liberia. Never mind the fact that behind the thin veil of ‘institutional democracy’ lies an institutionalised corruption backed by repressive methods. Never mind either, the acute deprivation of the population and the total collapse of the country’s social and structural fabric.

The truth is that the endemic poverty which was the breeding ground on which the civil war of the 1990s fed, still prevails. Only now, it is compounded by the hatred generated and suffering caused by the war among the population. But why should that bother Blair and the other imperialist leaders as long as a western-backed regime manages to impose just enough political stability to allow imperialist companies to loot the country’s resources? Until, that is, the day that the very same factors produce another catastrophe.