John Wight argues that the anti-war movement has failed to live up to the challenge

After four years of existence it is time to face some hard truths with respect to the anti-war movement in this country. And in facing those truths it becomes impossible to deny that by and large this movement has failed to effectively challenge Blair’s government with respect to the war; failed completely to impact on the government’s ability to aid the US in the prosecution of the war; failed to precipitate the political crisis required to affect the government’s policy or plans with respect to the war; failed to turn the mass support present in the run up to the war into the kind of vibrant, conscious and militant movement required to constitute any kind of challenge to the status quo after three years of war and occupation.

We only have to look at the recent deployment of more Scottish troops to Iraq, the recent announcement by the government that another 6,000 British troops are to be deployed to Afghanistan, to see evidence of the absolute failure of the anti-war movement to present a strong challenge to the ruling class.

Not that anyone should glory or derive satisfaction from this sad state of affairs. On the contrary, one of the biggest regrets all socialists and people of consciousness should experience, now and in years to come, is that such a major opportunity was lost to challenge the State and alter the course of history in as fundamental a way as was undoubtedly possible at the height of the anti-war movement in the run up to the war in late 2002 and early 2003.

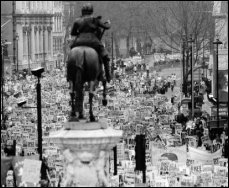

February 15, 2003 was a historic day not only in this country but throughout the world. On that day, in over 600 towns and cities internationally, an estimated 15 to 20 million people took to the streets to raise their voices against war, against imperialism; against, by extension, the free market variant of capitalism which lies at the root of the war in Iraq and the current crisis facing our planet.

That said, the only two countries in which this outpouring of anger and protest could possibly have had any meaningful effect were the UK and the US, given that these were the two nations leading the march to war.

Within the US on that day, despite it being a nation in the clutches of a wave of nationalism and fear post-9/11, 2 million came out in over 150 towns and cities to raise their voices against going to war. For those involved the sense that something important was or could be happening – the laying of the foundations of a new political movement of such power and force that it could not simply be ignored by the ruling class – was palpable. However, for potential to materialise into actuality human agency in the form of conscious leadership must be present. Alas, in the case of both the US and UK anti-war movements it is precisely this kind of conscious leadership that has been lacking. And whilst the US anti-war movement can perhaps offer the excuse that they represented the minority view in the nation as a whole, given the fear and nationalism that had been whipped up by a government aided and abetted by a complicit media, the UK anti-war movement cannot.

When you are two million in the streets of London you own the city. It is yours, undeniably and emphatically. It then becomes a question of what you do with the city on the day and in the hours that it is yours. There is no question that on February 15, 2003, a political crisis could have been created if only the leadership had seen and then seized the opportunity. What was to stop them taking over the Houses of Parliament, Buckingham Palace, indeed any major symbol of ruling class power and privilege? Nothing stopped them except their own lack of courage and willingness to mount a serious challenge to the British State.

Rather than rely on the moral rectitude of a ruling class in whose interests this war was about to be waged, the leadership of the movement on this day had an obligation to seize the opportunity presented by 2 million people on the streets to take the struggle as far as they could.

Yes, there may have been violence.

Yes, people may have been hurt.

But in comparison to the tens of thousands of innocent Iraqis about to be slaughtered, the one and a half million already killed due to sanctions, surely this would have been small price to pay for the very real possibility of rocking the government back on its heels and seriously hampering Blair’s ability to continue to support Bush and the right wing cabal surrounding him.

The knock on effect which such a crisis in the UK would have had on US antiwar movement and US body politic is anybody’s guess.

What we can say for certain is that there would have been one, and that it would undoubtedly have produced more political and social opposition to the war in the US than there was.

History provides irrefutable proof that peaceful protest only ever produces marginal gains for working, poor and/or oppressed people, while militancy and force can and does alter history.

The Labour movement, both at home and abroad, was built on the back of violent struggle, as was the movement for women’s rights, gay rights, and so on. The antipoll tax movement was a movement of mass civil disobedience which culminated in the riot of Trafalgar Square, an event which shook the British ruling class to its foundations and led directly to the fall of Thatcher.

From the streets of Ireland to the townships of South Africa, and most recently in the streets of Paris, it has been the willingness of people to confront the state, thus exposing its true savage and violent nature, which has radicalised movements and thereby produced qualitative change.

Many of a weaker consciousness within progressive movements continually tout the example of Gandhi or Martin Luther King as the model to emulate as a way forward to social change. This does a disservice to the truth and a service to the establishment, who would enjoy nothing better than to see ineffective peaceful protest after protest take place while they continue to plunder the planet.

In the case of Gandhi, the British Empire had become unsustainable, with the collapse of the British economy after World War II, and it was either sacrifice political power in India in order to retain economic power in the face of Gandhi’s peaceful and benign movement, or face the real possibility of losing it all in the face of the violent and secular forces that were also arrayed against them, and which were attracting increasing support away from Gandhi. The British opted for Gandhi.

Something similar took place with respect the US Civil Rights Movement led by MLK. His nonviolent movement was only as effective as it was due to the rise of black nationalism in black ghettoes represented by such figures as Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, Fred Hampton, and others. The US government, under John F. Kennedy and later Lyndon Johnson, finally caved in and embraced MLK and the cause of black civil rights, a man and a cause whom the white establishment had previously reviled, in order to nullify and check the rise of the much more potent black militancy which constituted the real threat to the status quo. Indeed, at one time J. Edgar Hoover, then head of the FBI, declared the Black Panthers to be the biggest threat to the internal security of the United States. It was this militancy, the threat it posed, which led directly to the rise of MLK and the nonviolent Civil Rights movement that he led.

The last national demonstration against the war in London, which took place in September 2005, was pitiful. A mere 25,000 people marched behind the empty and anodyne slogan, ‘March For Peace And Liberty.’ A slogan of which the Salvation Army would be proud, surely this demonstrates beyond a shadow of a doubt the degeneration which has taken hold within the antiwar movement. It is a movement shorn of all militancy, fire and coherence, one that has never managed to break out of a comfort zone consisting of replicating the same tired and worn actions time after time, in the forlorn hope that somehow, miraculously, they will suddenly produce the desired result, cause Blair to experience some sort of Damascus moment and order the withdrawal of British troops from the Middle East.

This will not happen. As a complement to the courageous resistance being offered by the Iraqi people to the occupation, the UK antiwar movement must take a long hard look at itself. Nothing will change significantly unless people are willing to make sacrifices and take risks. The only effect that attending a peaceful demonstration has is to make those participating feel better. This clearly isn’t good enough.

Ultimately, the verdict of history will be a harsh one unless sooner rather than later the antiwar movement moves beyond the impotence associated with bourgeois pacifism.