We are posting this article by Johnnie Gallacher, who provided his own introduction:-

As society stands hesitating at the ecological fork in the road to either ecosocialism or suicide, reflecting upon the unlikely political alliance between John Maclean, the revolutionary socialist, and Ruaraidh Erskine, the aristocratic Gaelic nationalist, can offer valuable insights. These relate to the unnecessary divide between industrial city socialists and rural liberation movements, and how this division can be bridged, as indeed it must be. This article builds upon Gerard Cairns’ biographies of the two early 20th century Scottish political figures.

THE ODD COUPLE: RUARIDH ERSKINE AND JOHN MACLEAN

Gerard Cairns (2017) The Red and the Green – A Portrait of John Maclean. Calton Books.

Stuart Erskine (he would later change his name to Ruaraidh) was born in 1869 to an English mother and a blue-blooded Lowland father descended from the historical aristocrat John Erskine, Earl of Marr, who had led the failed 1715 Jacobite rising. The family mostly lived in the south of England but frequently spent time in Edinburgh. From the late 1880s, Erskine became politically active as an eccentric Tory Jacobite monarchist. To most people, Jacobitism was by then no more than a historical curiosity which certainly posed no threat to the establishment. Tellingly, Erskine was most willing to co-operate with ‘the Hanoverian enemy’ to oppose the growing movement for suffrage and democracy.

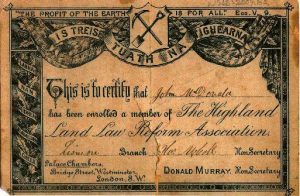

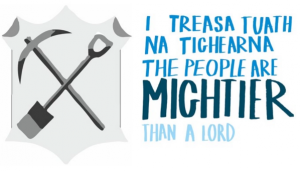

Perhaps the only redeeming feature of young Erskine’s politics was his support for Scottish Home Rule. The Scottish Home Rule movement had considerable organisational overlap with the Highland Land League (HLL), who, following on from decades/centuries of Clearance and oppression, had spent the 1870s and 1880s agitating for the rights of rural communities. In 1886, the HLL’s tireless campaigning successfully resulted in the government accepting the establishment of the Crofting Commission and passing the Crofters Holding Act legislation.

Having achieved its early aims, the HLL turned some of its energy towards Home Rule. The Scottish Home Rule Association (SHRA) published its manifesto in 1887 for full Scottish devolution. Erskine subsequently joined the SHRA London branch around 1891. Prior to joining, Erskine lacked any grounding in Scottish politics beyond obscure sentimental Jacobitism. His involvement allowed him the opportunity to mingle with activists from Scotland and Ireland and to learn from them. There was co-operation between the SHRA the more advanced Irish Home Rule movement, which had similar organisational overlap with the Irish Land League. Regrettably, the Highland Land League took a limited territorial scope, unlike its counterpart’s all-Ireland approach. This flaw contributed to some of the tensions in Scottish politics which are explored below.

Erskine suffered a series of family deaths in 1890s triggering a personal identity crisis. He developed self-awareness of his snobbish upper-class chauvinistic conduct. His Home Rule politics evolved into support for Scottish independence. He moved north to Scotland and was privileged to have time to learn Gaelic to fluency. He relinquished his birth name Stuart, the name of the Jacobite kings.

Reborn with the Gaelic name Ruaraidh, Erskine attended the 1899 pan-Celtic congress in Cardiff held during the annual Welsh Eisteddfod festival. Meeting Irish nationalist leaders Pádraig Pearse and Arthur Griffith, Erskine depressingly realised that the passive bureaucracy of Scotland’s Gaelic language leadership stood in stark contrast to both the intense cultural vibrancy of Celtic Wales and the politicised vigour of the Gaelic League in Ireland.

Determined to do something about it, Erskine founded the innovative Gaelic newspapers, Am Bàrd (1901-1902) and Guth na Bliadhna (1904-1925). These journals were well-regarded by native speakers, for while previous Gaelic papers usually reverted to English when dealing with the most serious political affairs, Erskine truly gave Gaelic equal footing. Erskine could have reached a wider audience with an Anglophone publication, but he was fuelled by passion, promoting Gaelic as the heritage of all the entire Scottish nation. The letters section of Guth na Bliadhna arguably demonstrates that a shift was occurring from Gaelic national consciousness towards organised political Gaelic nationalism.

Far from navel-gazing, Guth na Bliadhna featured articles on wide-ranging geopolitical topics, thereby strengthening ties between Scottish nationalists and other self-determination movements for example Poland and especially Ireland. Erskine looked at Irish politics with envy, for in 1910 the Irish Parliamentary Party (Home Rulers) held the balance of power in Westminster. Although they had not yet won any elections, Erskine was in awe of the more radical abstentionist programme of Sinn Féin. By painful contrast, Scotland remained stuck inside the two-party system of Tory and Liberal. Labour had split from the Liberals in 1900, but in Erskine’s view were too weak on the national question, even if they enjoyed the support of the Highland Land League from 1909, for an alliance of the rural agricultural and urban industrial working classes. There was the Highland Land League’s Crofters Party, but it was confined to the Highlands and Islands where its electoral success was limited.

In 1909/1910, Erskine and others set up the Scots National League (Comunn nan Albannach) in London, the first non-unionist Scottish patriot organisation in decades. It was a failed attempt to replicate the Highland Land League without the restricted territorial remit. However, it fell into hiatus around 1913. It was successfully revived in 1920 with the help of the Glaswegian socialist John Maclean. Until then, Erskine’s main political contribution remained using his journals to lay the cultural foundation from which politics could prosper.

An anecdote from shortly before the outbreak of the First World War demonstrates the extraordinary convergence which would later occur between Erskine and Maclean. Erskine timed the launch of his new journal The Scottish Review (1914-1921) with the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn in June 1914. By contrast, writing in the pages of the Social Democratic Federation’s newspaper Justice, Maclean wrote that ‘freaks of the propertied class are doing their best to excite us all about Robert the Bruce and Bannockburn, a battle fought six hundred years ago by serfs for the benefit of a few barons’.

It was during WW1 that the cultural democratic ground which Erskine had prepared began to sprout a well-formed left-wing Scottish nationalism. Writing in Guth na Bliadhna, Erskine advocated the rights of stateless nations to secede from empires. In The Scottish Review, Aberdeen trade unionist William Diack argued that stateless nations should be favoured in the post-war land redistribution. They were, he said, not to blame for the mass fratricide and trauma across Europe; empires were. The Scottish left would go on to organise around this message.

It was also during WW1 that Maclean really came into his own as a revolutionary socialist. While established officials in the trade union HQs supported the imperial British war effort, Maclean agitated incessantly, spreading the message ‘no war but class war’ and supporting wildcat strikes for working-class self-defence, including the successful women-led rent strike. He lost his job as a teacher and, along with other leading socialists, was jailed in 1916, remaining imprisoned for around a year.

As Maclean was jailed, Erskine was elected vice president of the Highland Land League. By then, the League had cut its ties with the Scottish Home Rule Association and were instead advocating Scottish independence. Drawing upon certain Irish revolutionary traditions, the Highland Land League had also developed a more culturally expressive character. The 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin for Irish independence would have been an inspiration to them, but it was severely condemned by the Scottish and Irish Home Rule movements who sought to stick to top-down bureaucratic strategies and to work within the frameworks of Union and Empire. The British left overwhelmingly failed to comprehend or appreciate the great anti-imperialist rebellion which had been made in Dublin. Yet, risking punishment from wartime censorship laws, Erskine’s publications celebrated what had happened.

Maclean was released from jail in 1917 and devoted his energies as an educator in the Scottish Labour College. The curriculum’s omission of Scottish history was criticised in The Scottish Review; why did Maclean skip over Marx’s treatment of the Highland Clearances? Maclean’s parents ended up in Glasgow due to the Clearances, yet as a union-oriented member of the British Socialist Party, Maclean hadn’t yet found any interest in his own roots.

However, where Erskine and Maclean agreed was that the Russian revolutions gave a glimpse of a more just world that would emerge from the war. Erskine was particularly pleased with the Bolshevik policy of self-determination for all peoples, even if it was not to last. As the new Soviet Republic withdrew Russia from of the imperialist war in November 1917, the Scottish left made calls for an immediate peace conference. Erskine was focused on securing independent Scottish representation at that conference.

He was inspired by US President Woodrow Wilson’s forward-looking statements about the post-war land redistribution and his idealistic vision of united nations free from imperial aggression. Although Wilsonianism lost credibility upon the American entry into the war in April 1917, Erskine’s campaign continued to take a credible left-wing character. The Scottish Iron Moulders’ Union took out a full back page ad in The Scottish Review pledging their support. Late in 1918, the campaign released a ‘national memorial’ document. This was subsequently translated into French in the hope of being used as a pass of admittance into the Paris Peace Conference. It was signed by 43 candidates of the December 1918 General Election, including several of the successful Glasgow Labour candidates.

Maclean, the unsuccessful Labour candidate for the Gorbals initially declined signing the petition, stating that his ‘blood revolts’ against thanking Wilson for advancing the cause of self-determination, ‘he has done nothing and will do nothing for home rule anywhere, as he is but the representative of brutally blatant capitalism in America… that means to crush Mexico… as it already has the Philippine Islands and Cuba’. However, Maclean later reconsidered his refusal and signed the petition, which in fact held no candle for Wilson. This brought Maclean’s first direct contact with Erskine.

That same 1918 khaki election – the first in which all adult men could vote – saw Sinn Féin win 73 of the 105 Irish seats. This included socialists such as Constance Markiewicz and Liam Mellows. The Irish Parliamentary Party won just 6, down from 67: the Irish Home Rulers had been replaced by a more radical independence campaign! As per their manifesto, the elected Sinn Féin candidates refused to recognise Westminster’s sovereignty over Ireland and instead took their seats in a new independent parliament, Dáil Éireann. The Dáilpassed the Irish Declaration of Independence at its first meeting on 21/01/1919. Erskine was inspired at these events. A guerrilla War of Independence to secede from the United Kingdom broke out on the same day.

Realising the more advanced Irish state of play, Erskine advocated a joint Scottish-Irish struggle for representation at the Peace Conference. Yet even with open rebellion in Ireland and support from the Irish-American diaspora, the Dáil failed to secure Irish representation at the Paris Peace Conference. It is no wonder then that Erskine’s strategy of piggybacking the Irish national movement failed.

Over the course of 1919, the Scottish campaign committee grew to fifteen, including four MPs, two trade union general secretaries and two newspaper editors. Alas, the negotiations were coming to an end. French President Poincare acknowledged receipt of the petition, but no more was done. In retrospect, it was a rather ineffective fame-fuelled letter-writing campaign.

The right of self-determination was in general reserved for nations situated within defeated powers like the Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires. Catalonia, for example, also failed to gain representation; Spain had been neutral throughout the war. Even in defeated empires, desires for self-determination were balanced against the ambitions of the victorious empires. For example, the former Ottoman Empire was mostly carved up between Britain and France with no regard for ethnicities or delicate cultural intricacies. An oversight that had bloody repercussions which persist to this day in the Middle East

Following the Russian Revolution, new Soviet-backed ‘democratic centralist’ Communist Parties were established around the world. Numerous groups on the British left amalgamated to form the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) in 1920. This included the British Socialist Party, who had expelled Maclean and joined up. Though he had previously been the Bolshevik consul in Scotland and had had Russian streets and even a Russian village named after him, Maclean refused to join the CPGB. He cited his chief reason as the political nature of some of those promoted to leading roles in the new party. For example, Lieutenant-Colonel Malone MP for the Liberals and Mr Menell, director of the Daily Herald. Why were British establishment figures being promoted to key Communist offices while the British Empire waged war on revolutionary Russia? As the historian Allan Armstrong has recently outlined, Maclean’s waning support for the union was by no means one of the main reasons for his refusal.

During this period of reorganisation on the Scottish and international left, in July 1920 Maclean hosted Erskine at his home in Glasgow. Erskine was in a position to facilitate Maclean’s then-embryonic move towards Scottish republicanism. Though the left at that time generally placed its faith in the development of urban industrial society, Erskine encouraged Maclean to take more of an interest in his rural Gaelic heritage. Erskine’s links with Irish nationalism and with the Highland Land League spanned decades, whereas Maclean was only starting to make these connections, having befriended two Irish Republican prisoners in Peterhead Prison in 1918. In 1919 Maclean visited Dublin, addressing an assembly of Irish socialists he argued that the Irish struggle ‘depended on the revolt and success of British labour’. He was berated for his continued unionism and spent the ferry journey home in deep contemplation.

A year later, at the time of his pivotal 1920 meeting with Erskine, Maclean’s position had developed. He went to Ireland again after the meeting. Although no records survive of this trip, it is safe to assume that Maclean’s understanding and support had grown. Once back in Scotland, he immediately travelled up to the Isle of Lewis to visit land raiders. English industrialist Lord Leverhulme had bought the entire island in 1917, pledging to industrialise and modernise the economy. Veteran soldiers had been promised ‘homes fit for heroes’ by the British Prime Minister but were instead greeted with Leverhulme’s unwelcome changes to Lewis. They resorted to the old tactic of land raiding as thirty ex-servicemen occupied two farms on the east coast of Lewis.

These crofters delivered a bold statement to Leverhulme. ‘You have bought this island, but you have not bought us, and we refuse to be bondslaves of any man. We want to live our lives in our own way, poor in material things it may be, but at least it will be free from the factory bell; it will be free and independent.’

Leverhulme responded to the land raids with a divide-and-conquer strategy. He closed businesses in Stornoway, blaming the raiders. The laid-off Stornoway workers didn’t see the big picture, and were enraged at the audacity of the land raiders. Maclean lamented the lack of understanding and solidarity between town and country. A rant about Maclean in the Stornoway Gazette captures the contradictions of the left. ‘As a paradox this takes some beating: there must be no wage earners on Lewis, yet a Dictatorship of wage earners is to rule the great Commune which this hare-brained creature advocates. So that rules Lewis out of any ‘ruling’ that is to be done.’

Maclean was in fact advocating an alliance of the rural agricultural and urban industrial working classes. This was in contrast to most city socialists, who dogmatically believed that socialism could only emerge in industrial capitalist settings. They saw the crofters as peripheral and irrelevant, and even looked forward to the destruction of the crofting community and the proletarianization of the crofters. These dogmatic socialists did not realise that non-proletarian forces’ struggles against the imposition of capitalism can lead to socialism, whether linked to socialist struggles within capitalist economies or not.

To his credit, Maclean had embraced the humanism and multilinear views of later Marxism; emancipation, liberation and self-determination in its widest sense. Unfortunately, Maclean was in a minority on the left and ‘economism’ prevailed. The same is true of today. Most socialists are content to demand ‘a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay’, and Maclean’s much more revolutionary call that ‘we are out for life, and all that life can give us’is drowned out.

Maclean’s views mirror those of Gramsci. The two Marxists travelled in the opposite direction to each other with regards to their views on political union and nationalism in their respective countries. Gramsci started out as a rural left-wing Sardinian nationalist, but in time came to favour working-class Italian unity. Nonetheless, the matured views of both thinkers emphasised the need for unity between the subaltern classes in rural agricultural and urban industrial areas.

Unfortunately, in neither country was this message a great success. The issue remains unresolved and demands further attention, in line with the RSP’s position that the Scottish left should be decentralised from Glasgow, and that activists outwith the central belt are incidentally best positioned to tackle serious issues such as land redistribution and ecological radicalism.

Just how big a deficiency is it to overlook late Marxism? Maurice Brinton powerfully argued in his life-affirming 1970 booklet The Irrational in Politics that the deformation of Soviet communism can be attributed to the fact that late Marxism did not gain sufficient understanding.

- The Irish Tragedy: Scotland’s Disgrace

- Irish Stew (mentions the SHRA, Erskine and Guth na Bliadhna).

- Scotch Broth (mentions Erskine).

- Highland Land Seizures (on the Lewis Land Raids).

- Literary Note (a short reply to Tom Johnston’s History of the Working Classes in Scotland regarding primitive communism).

- A Scottish Communist Party

- Open letter to Lenin (on the CPGB).

Maclean’s subsequent writings show the shift completed, most notably ‘All Hail, the Scottish Workers Republic!’ (1922). Admittedly this is more of a propaganda piece than a detailed theoretical tract. It gives an overview of Scottish history, promoting the Jacobite Risings as working-class history. This would have bewildered the union-oriented left in the CPGB and Labour. Be that ‘union-oriented’ as regards the Anglocentric United Kingdom, where the southeast of England is the centre of gravity, or as regards the Soviet Union, where the west of Russia was the equivalent, and where peripheries like Ukraine and Georgia suffer(ed) greatly.

The widely misunderstood concept of ‘clan communism’ was especially ground-breaking territory and has been taken as evidence that CPGB’s intra-left sectarian slanders against Maclean’s mental health were true. However the concept echoes Engels’s 1844 book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, James Connolly’s 1910 booklet Labour in Irish History, and indeed Erskine’s 1922 article ‘Celtic Tribal Communism’, which featured in Maclean’s Vanguard journal.

When the Scots National League, that pre-war London-centred flash in the pan, was revived in Scotland in 1920, one of its first activities was an historical commemoration chaired by Maclean in Arbroath to mark the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath. Considering his 1914 remarks on Bannockburn quoted above, Maclean had evidently come a long way. He would have viewed the medieval text with interest as a declaration of Scottish independence and an expression of proto-republican conditional support for Robert the Bruce, albeit ‘for the benefit of a few barons’.

John MacArthur, editor of the League’s Liberty journal, was a diehard Rangers supporter who sold copies of the Scottish Republican paper outside Ibrox on matchdays and contributed football fan humour to Liberty. Irish republican Cathal O’Shannon addressed the League, warmly narrating his Ulster-Scots heritage. At the same time, Erskine was a prolific author and publisher of Gaelic Catholic prayers and hymns. This is to say, that the movement sliced through sectarian stereotypes with down-to-earth humanist authenticity.

In the run-up to the November 1922 General Election, Scottish National League leaflets bearing Erskine’s signature asked Scots to abstain from voting, and to form a national convention which could join the League of Nations. This was a poorly executed attempt to replicate Sinn Féin’s 1918 abstentionist tactics. Sinn Féin was only successful because independence-supporting Irish voters did vote. Who was to form the Scottish national convention? No candidates had been stood or endorsed by the League. John Maclean stood as an Independent Communist candidate for the Gorbals, betraying a lack of cohesion within the Scottish republican/nationalist movement. Beneath the surface, they were divided over the Irish Civil War.

Nationalists such as Erskine posited that the dominion status of the Irish Free State could be a halfway house to a Republic. The absence of dialogue on the Northern Ireland partition betrays a complete lack of empathy. Having previously supported Home Rule for Scotland, the Scottish nationalists had more-or-less previously desired a ‘Scottish Free State.’ Yet they could never have accepted Edinburgh and the Borders be removed from this polity and renamed ‘Southern Scotland.’

Though Maclean was in HMP Barlinnie for most of the Irish Civil War, his associates were involved in shipping weapons to the anti-Treaty Republican Army. The majority of the Irish Republicans in Scotland supported the anti-Treaty side; support was higher among the diaspora. In November 1922, Maclean wrote to Irish President Cosgrave, on behalf of ‘four thousand ‘Red’ and ‘Green’ supporters of my fight for a Scottish Workers’ Republic’, protesting the execution without trial of four imprisoned anti-Treaty members of Dáil Éireann . The number refers to the 4,027 people who had voted for him in the 1922 election.

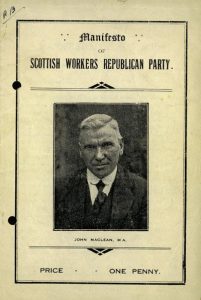

In April 1923, Maclean established the first ever political party in favour of Scottish independence, the Scottish Workers Republican Party. Maclean had intended to stand in the December 1923 General Election but withdrew from the race due to ill health. He had endured years of political persecution and the stress took a severe toll on his family life and health. He died on St Andrews Day, a week before the election. Shortly after Maclean’s death, Irish socialist leader Jim Larkin predicted an exodus of working-class Scots from the Scottish National League to the ranks of the Scottish Worker Republican Party. This was wishful thinking. The Party was dissolved in 1932.

What happened to the Scottish National League? Tom Gibson, a right-wing enemy of John Maclean, managed to marginalise Ruaraidh Erskine, and subsequently stripped away the League’s Celtic idealism, internationalism and radicalism. The independence stance was gradually diluted, and the organisation was transitioned into a drab, bureaucratic, conventional Home Rule-supporting political party. This was the National Party of Scotland, established in 1928, equivalent to the Irish Parliamentary Party, which in 1934 merged with the Duke of Montrose’s right-wing Scottish Party to form the SNP. Erskine regressed into the eccentric aristocratic obscurity of his youth. He went from ‘Ourselves Alone’ to ‘Myself Alone’ (bho Sinn Féin gu Mi Fhin) decrying Scotland as a ‘decadent nation… imitators and copyists of England.’

In truth, Erskine was never a socialist – he just worked with socialists when doing so was politically expedient to advance the cause of Scottish self-determination, just as Maclean worked with Scottish nationalists to further the cause of a pro-independence party of the left. Unfortunately, neither Erskine’s Gaelic Scotland, nor Maclean’s Scottish Workers’ Republic play figure prominently in Scottish politics. Not yet anyway.

2.5.22

Also see

Allan Armstrong’s 2018 Review of ‘The Red and the Green – Portrait of John Maclean’ by Gerard Cairns. URL: http://republicancommunist.org/blog/2018/06/22/allan-armstrong-reviews-the-red-and-the-green-by-gerard-cairns/

Gerard Cairns’ response. URL:http://republicancommunist.org/blog/2018/07/25/still-talking-about-john-maclean/

Video of Stephen Coyle’s lecture on Scotland and the Irish Revolution. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yZ3OtJKqhx4other ______

Other articles by Johnnie Gallacher

Recovering repressed memories from Scotland’s formative period

What is the Crown and what is republicanism?